Beginning in the last half of 2016, many indie authors reported sharp declines in their Amazon sales. Some wonder if a global slump in sales could be to blame, while others point to the rise of Amazon's imprints as a possible cause. More than a possible cause: I've heard authors express absolute certainty that Amazon is using its corporate might to shoulder aside non-Amazon imprints.

It's that latter theory that prompted me to examine Amazon's top sellers.

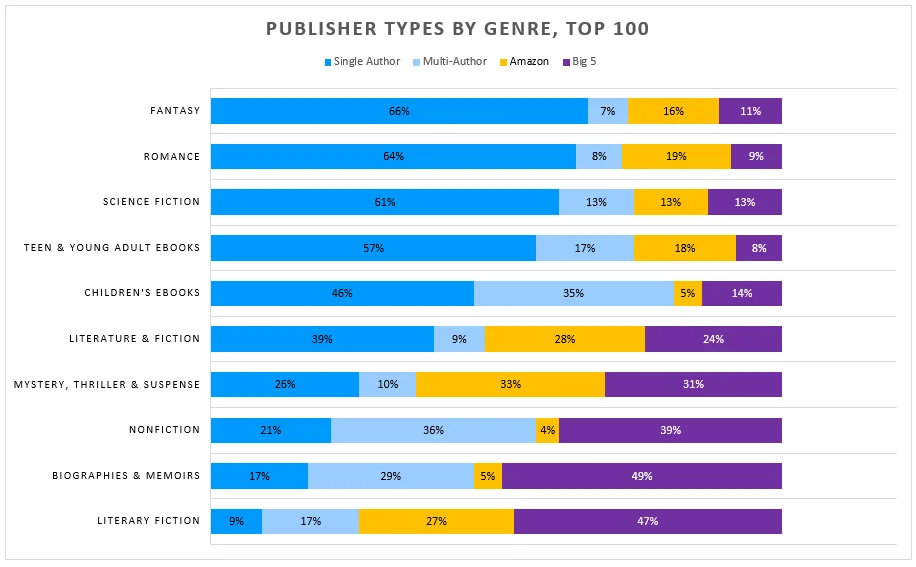

I took a long walk through Amazon's pages, looking for interesting patterns that might shed light on the situation. Ultimately, I decided to focus on the Top 100 Paid lists for ten relatively high-level Amazon categories, a total of 1,000 titles. It's a tiny sample size in light of Amazon's 5.1 million ebook catalog, but if Amazon is gaming its own system to gain an advantage, it would likely be reflected in the top-selling titles.

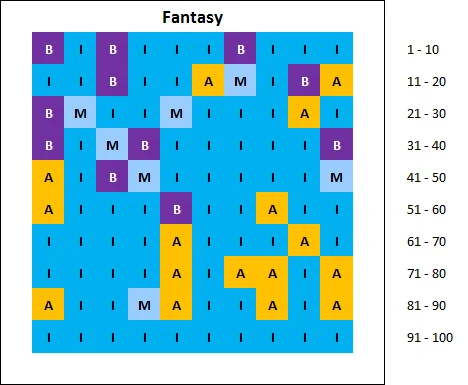

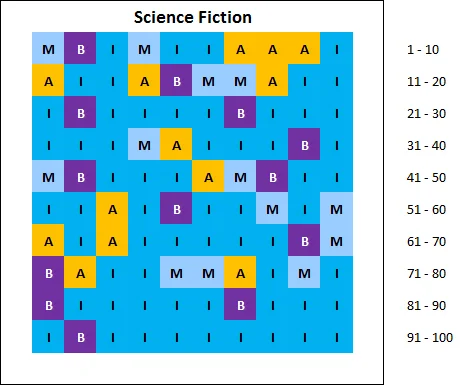

Borrowing a page from the data demigods at Author Earnings, I grouped each publisher into one of the following categories:

- Big 5 imprints owned by Hachette, HarperCollins, Penguin Random House, Macmillan, or Simon & Schuster.

- Amazon's traditional publishing imprints like 47North, Thomas & Mercer, and Lake Union Publishing.

- Single-author imprints that represent one author exclusively, including indie authors who publish through assisted self-publishing services.

- Multi-author imprints that don't belong to any of the above categories. This latter category encompasses a wide range of publishers, from small indie author collectives to well-known traditional publishing houses.

In the images below, each square represents one title on the Best Sellers list for a genre, laid out from left to right in rows of 10. Keep in mind that this experiment looks at only one moment of Amazon's volatile best seller rankings.

In the images below, each square represents one title on the Best Sellers list for a genre, laid out from left to right in rows of 10. Keep in mind that this experiment looks at only one moment of Amazon's volatile best seller rankings.

Fantasy

Indie authors (darker blue) dominate speculative fiction in general, and that's especially apparent in Fantasy. Big 5 imprints (in purple) hold relatively few top slots with perennial best sellers like Neil Gaiman. A larger number of Amazon imprints (orange) can be found scattered throughout the lower ranks.

Indie authors (darker blue) dominate speculative fiction in general, and that's especially apparent in Fantasy. Big 5 imprints (in purple) hold relatively few top slots with perennial best sellers like Neil Gaiman. A larger number of Amazon imprints (orange) can be found scattered throughout the lower ranks.

Science Fiction

Self-published authors make up more than 60% of the best sellers in Science Fiction, while the remaining slots are divided evenly among Big 5 imprints, Amazon imprints, and multi-author imprints. Penguin Random House accounts for half of the Big 5's hits in this genre.

Self-published authors make up more than 60% of the best sellers in Science Fiction, while the remaining slots are divided evenly among Big 5 imprints, Amazon imprints, and multi-author imprints. Penguin Random House accounts for half of the Big 5's hits in this genre.

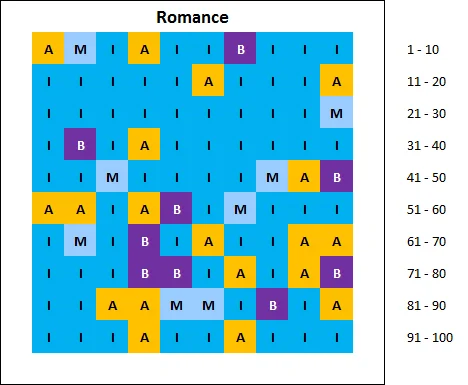

Romance

Indie authors also fare well in Romance, securing 64% of the best seller slots. Amazon imprints come in a distant second with 19% of the slots, mostly via the Montlake Romance imprint.

Indie authors also fare well in Romance, securing 64% of the best seller slots. Amazon imprints come in a distant second with 19% of the slots, mostly via the Montlake Romance imprint.

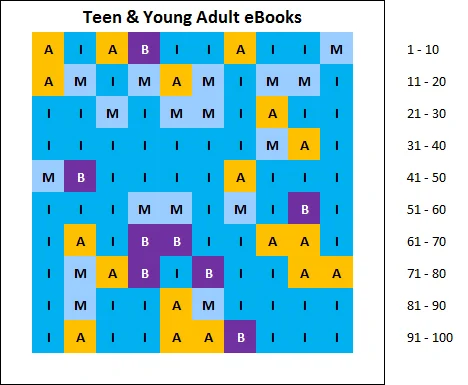

Teen & Young Adult

Teen & YA fiction is another stronghold for indies, who represent more than half of the best selling titles. Surprisingly, most of Amazon's best sellers here don't originate with their Teen and YA imprint Skyscape, but rather with 47North, their imprint for sci-fi, fantasy, and horror.

Teen & YA fiction is another stronghold for indies, who represent more than half of the best selling titles. Surprisingly, most of Amazon's best sellers here don't originate with their Teen and YA imprint Skyscape, but rather with 47North, their imprint for sci-fi, fantasy, and horror.

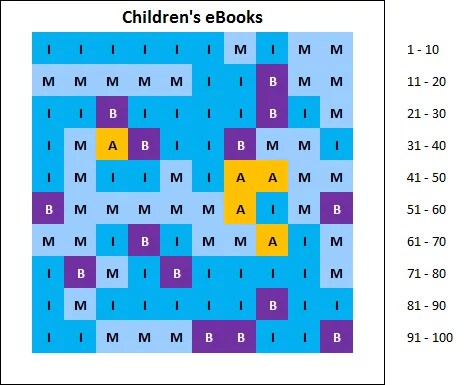

Children's eBooks

Harry Potter consistently rules in the Children's eBooks chart, and true to form, J.K. Rowling's digital imprint Pottermore — which we have categorized as a single-author imprint — comes close to a clean sweep of the top 10 slots. Even excluding these outliers, single-author imprints hold more than a third of the best seller slots. Amazon's Two Lions imprint fails to roar in this category, holding only five slots on the list, all at the 30th percentile or below.

Harry Potter consistently rules in the Children's eBooks chart, and true to form, J.K. Rowling's digital imprint Pottermore — which we have categorized as a single-author imprint — comes close to a clean sweep of the top 10 slots. Even excluding these outliers, single-author imprints hold more than a third of the best seller slots. Amazon's Two Lions imprint fails to roar in this category, holding only five slots on the list, all at the 30th percentile or below.

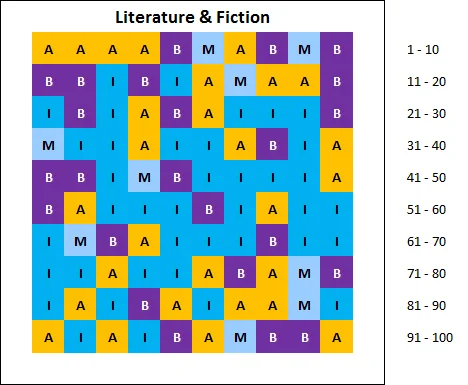

Literature & Fiction

In the broad, catch-all category of Literature & Fiction, the charts are more evenly divided. Indies hold a slight edge thanks to the category's preponderance of romance and erotica titles.

In the broad, catch-all category of Literature & Fiction, the charts are more evenly divided. Indies hold a slight edge thanks to the category's preponderance of romance and erotica titles.

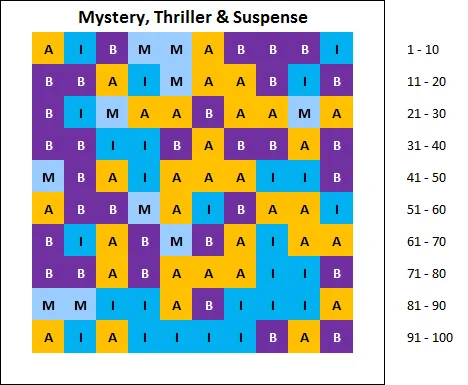

Mystery, Thriller & Suspense

This is a genre typically favored by traditional imprints, and competition is fierce. Amazon imprints are the dominant force here, swallowing up a third of the best seller slots. Another third is divided among the Big 5 imprints. Hachette's performance is particularly weak with only two titles in the Top 100 for this genre. Indies claim a quarter of the best seller slots, primarily towards the end of the cutoff.

This is a genre typically favored by traditional imprints, and competition is fierce. Amazon imprints are the dominant force here, swallowing up a third of the best seller slots. Another third is divided among the Big 5 imprints. Hachette's performance is particularly weak with only two titles in the Top 100 for this genre. Indies claim a quarter of the best seller slots, primarily towards the end of the cutoff.

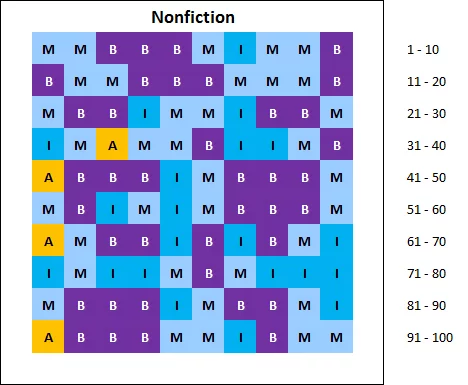

Nonfiction

Big 5 imprints are strong in this category. Of the 39 Big 5 titles in the Top 100, 14 belong to HarperCollins imprints. Independent publishers like W.W. Norton, Callisto Media, and Bonnier Corporation take second place with 36% of the Top 100, and self-published imprints make up a respectable 21% of the field.

Big 5 imprints are strong in this category. Of the 39 Big 5 titles in the Top 100, 14 belong to HarperCollins imprints. Independent publishers like W.W. Norton, Callisto Media, and Bonnier Corporation take second place with 36% of the Top 100, and self-published imprints make up a respectable 21% of the field.

If there is any truth to the suspicion that Amazon is algorithmically manipulating what customers see in order to favor Amazon imprints, the practice hasn't been applied to nonfiction titles: only 4 titles from Amazon imprints are in the Top 100, all ranking worse than the 40th percentile.

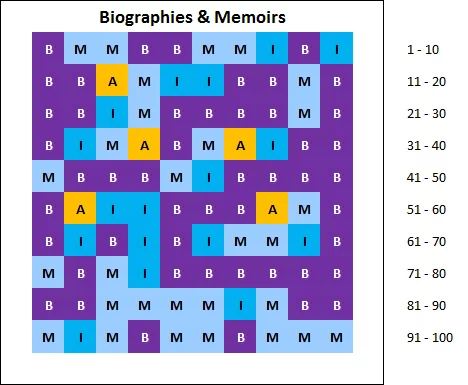

Biographies & Memoirs

Big 5 purple dominates the Memoirs chart, consuming fully half of the best seller positions. Penguin Random House and HarperCollins make up the bulk of these Big 5 titles. Like Children's eBooks and Nonfiction, Amazon imprints account for only 5% of the Top 100 titles.

Big 5 purple dominates the Memoirs chart, consuming fully half of the best seller positions. Penguin Random House and HarperCollins make up the bulk of these Big 5 titles. Like Children's eBooks and Nonfiction, Amazon imprints account for only 5% of the Top 100 titles.

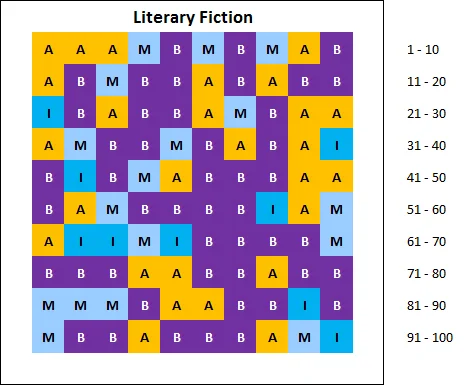

Literary Fiction

Pressured by Big 5's dominance of the genre (47% of the best selling titles) and the relatively new incursion of Amazon's Lake Union Publishing (25%), independent authors fared significantly worse in Literary Fiction. Less than 10% of the best seller slots are held by indies.

Pressured by Big 5's dominance of the genre (47% of the best selling titles) and the relatively new incursion of Amazon's Lake Union Publishing (25%), independent authors fared significantly worse in Literary Fiction. Less than 10% of the best seller slots are held by indies.

Another Perspective

These charts can be distilled into the summary below (click to enlarge).

A curious thing happens when you sort these genres by the percentage of Single-Author Imprints. In general, the larger the Big 5's share, the smaller the indie authors' share, and vice versa. That sort of tug-of-war isn't apparent from any other ordering of the data. This may be coincidental, but it's worth examining whether Amazon's share remains relatively constant while other publishers are in flux, or grows at the expense of those publishers.

Conclusion

The charts above offer an intriguing glimpse at how various publishers are represented in Amazon's Top 100 best seller lists. However, it is important to remember that they are merely snapshots, a very thin slice of data observed at one brief moment in history. Like a yearbook photo taken in the middle of a sneeze, the image they present may be contorted by unusual events.

With regard to the theory of Amazon manipulating sales, it's true that there are a host of ways in which Amazon could potentially favor its own products to the detriment of others. Amazon has near-total control over pricing, advertising, recommendations, reviews, shipping, communications with customers, reporting of statistics, and the display of products. Any of these factors could be used to tilt the playing field in Amazon's favor. But if Amazon were using these tactics, surely there would be a higher number of Amazon imprints in the upper echelons of their best seller lists.

Fortunately, there is no sign that Amazon has its finger on the scales. I have seen no evidence of algorithmic manipulation of Amazon's search results, sales rankings, or reviews to favor their imprints. In the short term, Occam's razor applies: the rise of Amazon's imprints may simply be due to a potent combination of quality books and savvy marketing.

We will continue to gather data in the coming months to look for trends and noteworthy shifts in the numbers.

OVER TO YOU

What are your thoughts on the success of Amazon's imprints? Do you believe Amazon is playing fair? Let us know in the comments below!

RELATED POSTS

This article will help me focus on what genres and stories I’m writing and prioritise those who are currently in better genres. Thanks for the information. It helps.

[…] eBook market. In addition, the company also makes money off of the many other books it sells. The Alliance of Independent Authors suggested that; “Amazon could potentially favour its own products to the detriment of others.” […]

Also, Data Guy in comments on the Feb 2017 AE Report.

“The reason I used the word “unsettling” is Amazon’s ability to drive, via algorithmic merchandising, which books are marketed most heavily to their customers and which aren’t. For me the question isn’t whether Amazon Imprints will continue to grow their share of ebook sales; the question is where Amazon will decide they should level off.”

An interesting study, John.

What it sorely lacks is relative numbers for context.

Here are 5.1 million ebooks. Maybe 5,000 of them are Amazon imprints, yet Amazon imprints manage all these top places, against how many indie titles and how many Big Pub titles?

I went to Amazon’s A-Pub page and followed Amazon’s own Thomas & Mercer imprint link back to the Kindle store. There are 1,048 results. 1,048 out of 5.1 million ebooks. Yet Thomas & Mercer has 33% of the top 100 in your snapshot.

The Montlake romance imprint, again following the link to Montlake books from the A-Pub page, turns up 1,426 titles. Out of 5.1 million. Yet almost a fifth – 19% – of the top 100 titles on Amazon come from Montlake.

Amazon’s 47 North imprint offers just 441 titles. That covers sci-fi, fantasy and horror. Your own snapshot shows 47 North taking 13 of the top 100 sci-fi and 16 of the top 100 fantasy slots, out of 5,1 million books.

Amazon’s Little A imprint covers both literary fiction and literary non-fiction. Your snapshot shows Amazon holding 27 of the literary fiction slots. Out of just 68 titles in total from this imprint.

Without the kind of software Data Guy has access to it’s not so easy to calculate how many of, say, the top 1,000 titles or top 5,000 (out of 5.1 million) are A-Pub titles, but safe to say it’s a lot.

Now let’s step back and look at the bigger picture.

In the most recent Author Earnings Report Data Guy identified A-Pub as having 14% of Amazon ebook market share. Data Guy, in said report, described the continuing rise of A-Pub market-share domination as “unsettling.”

You, John, offer a more complacent picture, by giving equal weight to A-Pub, Big Pub, Small Pub, indies, and whatever.

But they do not carry equal weight.

If we take A-Pub as having about 5,000 titles, then Amazon’s own titles represent less than 0.1 percent of the Kindle store, yet take 14 percent of all sales.

That suggests to me that Amazon clearly has its finger on the scale.

And that should indeed be seen as, in Data Guy’s words, “unsettling.”

Unsettling not because these are Amazon imprints – great quality titles from great authors, and of course Amazon is going to favour its own.

What is unsettling is that is that with the rise and rise of A-Pub (2,000 title released just in 2016, and as the AE Report clearly shows, A-Pub the only publishing segment clearly growing market share on Amazon) we content-suppliers are now in direct competition with our biggest retailer, be it for ebook sales, print or Kindle Unlimited downloads.

It’s true that if you measure the proportion of Amazon titles to the entire catalog size, they control a disproportionate amount of the best sellers. But the same can be said for Big 5 publishers, who control a sizeable chunk of the best seller lists.

And how much of the best seller list is controlled by indies, in comparison to the staggering number of indie publications? The number of books on the market doesn’t bear a direct relationship to the number of best sellers.

Nonetheless, as you’ve pointed out, this is the first time Amazon has truly been in competition with other publishers, and that is a frightening prospect. Their share of the market has to come from somewhere, and it remains to be seen whose plate they’ll be eating from.

This is far too narrow a slice of data to draw any strong conclusions from, but I expect we’ll see some interesting numbersin the coming months. Stay tuned.

[…] by our Watchdog John Doppler’s post a week ago examining relative sales on Amazon by the Big 5 publishers, Amazon imprints, multi-author imprints […]

Great article. I would have been surprised if it had appeared Amazon was manipulating sales. The fact is Amazon is in the business of making money, and I don’t think the company cares which book sell, but only that the company sells as many books as possible. The whole thing about their algorithm is showing customers the books that Amazon believes they are most likely to buy. I think part of the decline in Indie sales does have to do with the global slump in book sales. I also believe part of it is that the traditional publishers have been forced to take Indie publishing seriously and now are finding ways to compete more effectively. And with the rising popularity of self-publishing, the competition just gets more fierce each year. Over five million titles on Amazon. That’s just a mind-boggling number and it illustrates just how difficult it is to even have a book be visible on the platform these days.

“Amazon is in the business of making money, and I don’t think the company cares which book sell, but only that the company sells as many books as possible.”

The thing is, Larry, if Amazon sells our books or a Big 5 book it collects just 30% of the transaction. If it sells its own titles its collects 100%.

So now we can see what you conclude did not cause a 50+% drop or more in sales in the latter half of 2016 for some Indies. And that’s good to know; thank you for the hard work then and upcoming.

Still, we’re left with the mystery of what did happen to cause such a huge drop. DG has it that, if I remember correctly, Zon began favoring not its own imprints but the BP’s books over Indies. Someone correct me if I’m incorrectly remembering DG’s finding in this regard. I wonder what your comments would be to this theory that yes, while Amazon didn’t touch the scale to favor their own imprints they DID touch the scale to favor BP over Indies. Any truth to this?

Again, thanks for the great work.

You remember correctly, John.

John Doppler says he sees no evidence Amazon has its finger on the scale. Well, John, you also reference the “data demigods at Author Earnings.”

These are the words from Data Guy himself on how Amazon has its finger on the scales and basically decides how much market share we will or will not have..

Quote,

“Overall Amazon sales actually went *up* by about 4% in 2016.

But between May 2016 and Oct 2016 Amazon *indie* sales dropped, not just for KU titles but for non-KU indie titles, too. (although they seem to be growing back now.)

I think what happened is that the indie share of Amazon sales was getting too ridiculous (closing in on 50% of all Amazon purchases). So Amazon decided to pull some algorithmic merchandising levers behind the scenes (in their nightly marketing emails, for instance) to start pushing traditionally published ebooks at customers more aggressively (traditional publishers would probably say, “more fairly” )

Which had the near-instantaneous effect of downshifting indies to 40% or so of Amazon US purchases in October, rather than the nearly half(!) of Amazon sales that indies had been grabbing in May.”

Unquote.

Source: comments section at The Passive Voice.

http://www.thepassivevoice.com/2017/03/big-bad-wide-international-report-covering-amazon-apple-bn-and-kobo-ebook-sales-in-the-us-uk-canada-australia-and-new-zealand/

Of course when “Amazon decide(s) to pull some algorithmic merchandising levers behind the scenes” the “near-instantaneous effect of downshifting indie” sales can be catastrophic for individual authors.

Indeed, that’s a possibility, and nothing I’ve presented here precludes Amazon’s manipulation of those variables.

However, I’ve seen no verifiable evidence of it. Until we do have solid evidence of manipulation, all we’re left with is vague suspicions of what Amazon *might* do.

And marketing is the most likely avenue that Amazon will exploit, in my opinion, rather than manipulating the A9 algorithms to favor Amazon imprints. This experiment doesn’t touch on marketing at all.

In any event, this is just a preliminary, very shallow dip into a huge pool of Amazon data. It bears watching, and I’ll repeat these experiments to see if we can observe anything more concrete.

Excellent. Thank you. It’s good to have the myth destroyed. I wonder if it’s a turning of the tide with indies. Those who promote rise to the top.

Thanks for all your hard work on this, John. Very helpful graphics!

Fantastic analysis of the data, John – of course.

The results don’t surprise me. For around a couple of years I’ve noticed the growth in domination of my own genre by Amazon imprints. Part of this is their clever marketing, with pulsing prices lifting their titles towards the top ranks, which then impacts subsequent sales. But one thing to note about Amazon publishing is that a large number of their authors were Indie until their sales figures brought them to the Zon’s attention. This automatically skews their imprint titles toward the upper ranks in some genres.

The other thing this tells me is I should have stayed with science fiction 🙂

[…] Visualizing Amazon: Best Sellers […]

[…] John Doppler Beginning in the last half of 2016, many indie authors reported sharp declines in their Amazon […]

Thanks for sharing this information, John. It must have required days of research and compilation.

My pleasure, Kathy… literally! I’ve always had a passion for data visualization.

Infographics even I can get my head round. Now I can see why I’m struggling!

I’ve never seen the data presented this way–it’s utter genius. Of course it’s a snapshot view so it would be most valuable if you could track over time and watch how the patterns change.

I write in the historical mystery sub genre and your visualisation confirms what I already knew–that the mystery field is heavily dominated by trade publishing, with a few indies making a mark. All the more attractive to my eyes, as there’s more scope for an indie to compete using our particular marketing advantages.

I’d like to see a chart for the other aspect of my writing–historical fiction–as that’s so often left out, but I’m pretty sure that for what many people think of as HF (biographical fiction based on real historical personages) there’s a massive dominance of trade publishing. For the sort of thing I write–intended to appeal to genre readers who like a historical background–you’d need to look at the overall genre picture.

This makes me want to change my own research a bit, and study not only what my comps write but how they’re published, and at what price. It’s odd how seeing what I already knew represented in visual form has sparked ideas for strategy. Thanks for putting in the hard work, John!

Thanks, Jane! I’m tentatively planning quarterly updates, which I’ll put through the blender at the end of the year to see what we come up with.

This initial run was labor-intensive, but now that I’ve automated some of the work I’ll be expanding this data to include print editions. I’ll also run the numbers on a few additional categories, including Historical Fiction, Erotica, and Horror.

Suggestions are welcome!

That was two incredibly good ways of displaying the data.

Since I hope to be one of the great indie literary writers (small ego), it was discouraging to see (though I already knew somewhat) what a small section indies hold in that market.

I thought the Amazon literary imprint was Little A, not Lake Union, which is listed as ‘Contemporary and Historical Fiction, Memoir, and Popular Nonfiction.’

What it really means is that there is no recognized marketing plan that has pushed indies into the literary market, where they will compete largely with the big publishers. The bps are of the opinion that they own the category (and are probably ignoring the huge Amazon incursion).

Still, I’d rather have data than speculation, and this confirms what Author Earnings results are for the category.

Thank you, Alicia! It is odd that indies hold a fairly small slice of that pie, but on the positive side, the high number of traditional publishers in that genre would tend to disprove the myths that say “literary fiction is dying” or “literary fiction doesn’t sell”.

If the Big 5 can exploit that market profitably, so can indies.

You are correct that Little A is Amazon’s literary imprint. Genre boundaries are becoming hazier, and there are a few Amazon imprints that regularly slip across those divisions. One example we noted in the article is 47North, Amazon’s speculative fiction imprint which overshadows Skyscape (a teen & YA imprint) in the Teen & YA category.

[…] Read the entire article… […]