Orna Ross, Director of ALLi

We've all heard the widespread false news that self-publishers cannot succeed in the literary fiction genre. Orna Ross, director of the Alliance of Independent Authors, and an award-winning self-publisher of literary fiction and poetry, dispels the myths and gives guidance. With thanks also to Melissa Addey, Roz Morris and Hannah Jacobson of BookAwardPro.

What is Literary Fiction?

Literary fiction (litfic for short) is the genre of storytelling that explores the most complex social and psychological characteristics of the human condition, in original, expressive, and sometimes experimental ways.

The most defining quality of literary fiction is its original and skilful use of language.

NY Book Editors define literary fiction as a type of fiction that “doesn’t adhere to any rules. Anything can happen which can be both exciting and unnerving for the reader. Sometimes, literary fiction takes a common theme in mainstream fiction and turns it on its head.” Sometimes it's just an old story told uncommonly well.

Readers who enjoy literary fiction (or litfic for short) appreciate a writer's style and technique, and enjoy stories told in subtle, nuanced and original ways. That's utterly part of their pleasure in the work, what makes a book “good” for them.

Other readers, those who most appreciate plot, pace, and known patterns, can find litfic boring, puzzling or too much like hard work.

Literary fiction, historically and culturally, is often associated with a certain level of prestige, intellectual engagement, and artistic merit. It's seen as a form that challenges and engages rather than adheres to specific market-driven conventions.

This is why it is typically thought of as being more “highbrow” than other genres, appreciated more for its creative virtuosity than its commercial appeal. It is the stuff of which national and international literary prizes are made.

Classifying Literary Fiction

The classification of literary fiction is a topic of some debate in literary and academic circles. While it's frequently treated as a distinct category, especially in bookstores and publishing, whether it's a “genre” in the same way that, say, science fiction, romance, or mystery is a genre can be contested.

Literary is often a label that somebody else gives you. I don't think anybody sits down to write a literary novel. We write what we can, as best we can. The challenge I set myself as a writer is to write something that's honest and true, using the words, characters, and construction, that can capture everything I want to say (which, as my family can attest, is always a lot!).

As a reader that's what I most appreciate in a book, too. What Jane Austen defined as “only a novel. Only some work in which the greatest powers of the mind are displayed, in which the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties, the liveliest effusions of wit and humour, are conveyed to the world in the best-chosen language.”

We often define literary fiction by comparing it to what it is not: popular fiction, commercial fiction, mainstream fiction and genre fiction.

All of these create confusion.

Popular fiction: Many litfic works are highly popular, many books that are categorized as popular fiction fail to win readers.

Commercial fiction: By this logic, if a “literary” work sells millions of copies it would then move into the “commercial” category?

Genre fiction:

Mainstream fiction: Things get even more blurred when considering differences between literary and mainstream fiction, works that do not fit neatly into a specific genre category but appeal to a broad audience due to their general themes and accessible narratives.

Distinctions can be fluid, and a book might be categorized differently depending on who's making the classification.

Is Literary Fiction Just Another Genre?

All fiction belongs to a genre of some sort, as you discover when you first self-publish and have to assign a category to your book. Is literary fiction just another genre, once that is given privileged attention just because it's the kind of fiction people in publishing like to read?

Yes and no.

Litfic is a genre, with its own specific characteristics and conventions. In the publishing industry, it is treated as its own category, as evident in how books are marketed, where they're placed in bookstores, and the categories used in literary awards. And readers often approach literary fiction with different expectations than they would a genre or mainstream book.

On the other hand, unlike clearly defined genres like “cosy mystery”, “steampunk”, or “paranormal romance,” literary fiction encompasses a vast range of topics, settings, and approaches and resists such categorization. The emphasis on internal landscapes over external markers makes it less tied to specific tropes or settings.

So literary fiction both is and is not a genre. It embraces all genres, as well as being a genre in itself.

Often, it embraces multiple genres in one book. My novels are historical murder mysteries, multi-generational family sagas, women's fiction, and more.

Literary Fiction “Versus” Genre Fiction

- Genre Fiction is predominantly driven by plot, often adhering to established patterns and nuances of its specific genre. Less like to stop for discursive asides, less likely to deliberately puzzle and challenge the reader, the storytelling is immediate and approachable. Whether it's heart-tugging moments in romance or edge-of-the-seat moments in thrillers, the pacing in mainstream fiction keeps the reader eagerly turning pages to find out what happens next.

- On the other hand, Literary Fiction thrives on character-driven narratives. These tales often play with and transform genre expectations, pushing the boundaries of conventional storytelling techniques. Such writings are usually nuanced, avoiding clichés both in plot structure and language. Here, the narrative isn't just about the external journey but dives deep into the protagonist's inner world, the storyline, and the broader societal context. It may also rely on symbolism or allegory to impart a deeper takeaway.

This isn't about a hierarchy in writing quality. It's about distinct styles and approaches to storytelling.

It's worth noting that each genre has its own essence, and classifying one as superior to the other is plain wrong. Just as we wouldn't say a crime writer is inherently better than a romance writer, we shouldn't perceive mainstream fiction writers as any less skilled than those who write litfic.

Both styles of writing presents their own challenges and each requires a specific set of skills.

A writer's progression in their craft doesn't mean transitioning from genre to literary fiction. A genre writer honing their skills won't evolve into a litfic writer unless they were to make an active choice to do this, and most won't want to. Rather, they’ll perfect their own skills and talents in their own sphere.

By distinguishing literary fiction from genre fiction in this way, it's often implied (whether intentionally or not) that literary works have a higher value or are more intellectually “worthy'” than other forms of fiction. This creates an artificial hierarchy that can undervalue genre fiction, and create undue pressures for literary fiction authors.

Over time, what is considered “literary”can change. Books that were once deemed popular fiction in their time are now studied as literary classics. How many book prizewinners of 50 years ago are still read today? Similarly, many genre fiction authors have pushed the boundaries of their genres, incorporating deep thematic elements, complex character developments, and innovative narrative techniques.

It's hard to categorize creativity.

Reading and writing are inherently fluid and subjective experiences, and deeply personal. What resonates as “literary” for one person might be different for another. The terminology, though helpful for publishers, booksellers (which we are when we become indie authors) can sometimes constrain our understanding and appreciation of the vast landscape of fiction as writers and readers.

The market is usually driving these distinctions rather than the content of the book or the work of the author.

Qualities of Literary Fiction

Less escapist

In contrast to more escapist genres, where the primary goal might be to entertain or provide a temporary departure from reality (such as through fantastical worlds, thrilling events, or idealized romances), litfic tends to anchor its narratives in realities that are either recognizable or relatable. These realities might be rooted in the mundane, everyday experiences or in larger societal issues that are difficult to grapple with.

More true to life.

Emotions are usually mixed, characters often ambivalent, and situations a mix of good and bad–just like in life. And crucially, the characters' may not all live happily ever after.

Rather, litfic resolutions invite readers to imagine what happens in the afterlife of the book. Readers enjoy pondering the characters' futures in this way. They want the story to have a resolution, of course, but nothing too tidy, clichéd or unrealistic.

This truer-to-life quality is one of the things that attracts readers. Literary fiction readers need to be more open-minded and patient than the average reader, and appreciative of slow-burn storytelling that for them is as impactful and memorable as fast-paced plots are for others.

Attention to language.

For literary fiction writers, the way a scene is depicted can be as significant, if not more so, than the scene's content itself.

Oscar Wilde, when asked how his day's work had gone, spoke of spending the morning taking out a comma and the afternoon putting it back in. This quote is also sometime attributed to Flaubert, a notoriously slow writer. “I have just spent a good week,” he wrote to a friend midway through Madame Bovary, which took seven years to compose. “Alone like a hermit and calm as a god, I abandoned myself to a frenzy of literature. I got up at midday, I went to bed at four in the morning; I have written eight pages.”

Litfic writers can relate, as they work on crafting their sentences with meticulous care, using evocative language, intricate metaphors, and lush descriptions.

This is why literary fiction generally takes longer to write and why thinking in terms of word-count, which works so well for genre fiction writers, may not work for us.

Marketing Literary Fiction: The Challenges

Marketing literary fiction as an indie author poses unique challenges compared to other genres.

Here are some of the main difficulties and considerations:

- Undefined Target Audience: Unlike specific genres with well-defined target audiences (like YA or legal thrillers), literary fiction often appeals to a broad spectrum of readers, making it challenging to identify and target a precise demographic.

- Branding and Positioning: Creating an author brand around literary fiction can be more nebulous than, say, being a romance or horror author. The eclectic nature of literary fiction can make consistent branding a challenge.

- Less Defined Tropes: Genres often have specific tropes or elements that readers expect. Literary fiction doesn't have such clear-cut expectations, making it harder to market based on content.

- Lack of Series Potential: Writing series is a marketing advantage that indie authors have perfected. While genre fiction revels in series, and some literary fiction series are available, litfic is typically standalone.

- Competition with Trade Published Works: Many established literary authors are backed by major publishing houses with heftier marketing budgets and industry connections. For indie authors, competing in this space can be daunting.

- Reviews and Critical Acclaim: Literary fiction often relies on reviews, literary awards, and critical acclaim for visibility and validation. For indie authors, accessing major reviewers or getting nominated for prominent awards can be a significant hurdle.

- Distribution Challenges: Many bookstores, literary festivals, or events may have a bias towards traditionally published books, making it harder for indie authors to get physical shelf space or invitations to literary events.

Despite these challenges, many indie authors have found success with literary fiction by leveraging social media, building strong reader communities, engaging in book clubs, participating in indie author events, and employing creative marketing strategies that highlight the unique qualities and depth of their work.

Sometimes litfic authors get in our own way. We can be particularly resistant to marketing and promotion, have untested negative beliefs about self-publishing litfic, and repeat assumptions that we haven't tried and tested for ourselves.

There are many myths about self-publishing literary fiction but most of them are untrue.

Self-Publishing Literary Fiction: Mislabelling

ALLi Campaigns Manager Melissa Addey

The term “literary” has an intrinsic value judgment to many people, associated with “quality”. Thus, authors might label their work as literary with the belief that it conveys a certain level of professionalism, rather than aligning with the conventions and expectations of the literary fiction genre.

When readers pick up a book labeled as literary fiction, they come with certain expectations—complex characters, thematic depth, nuanced prose, and often a more introspective or contemplative narrative. If the book does not deliver on these expectations, readers might feel disappointed or misled.

Says ALLi's Campaign Manager, Melissa Addey:

“Often authors use literary to mean ‘good quality', which is not what literary fiction is. I searched for litfic as a genre on our member database and out of 200+ who had ticked literary as their genre, many did not seem to fit the genre. This is problematic. It implies the possibility of mis-selling books to the wrong readership, which causes a raft of problems.”

Authors who inadvertently mislabel their work might face backlash from readers or critics who feel the work doesn't “measure up” to literary standards. This can affect reviews, future sales, and the author's overall reputation.

As well as leading to less effective promotional campaigns, misplaced bookstore shelving, incorrect targeting of review outlets and more, implicit in confusion of “literary” and “quality” is the problematic assumption that genre fiction cannot also be of high quality. This can perpetuate snobbish attitudes toward genre fiction and undervalues the craft of genre fiction writing.

The Place of Prestige: Awards and Editorial Reviews

A paid editorial review from a brand name like Blue Ink or a prize win might not move the needle for genre readers, for litfic readers it can (sometimes) make a difference. On the other hand, litfic readers are a discerning lot and they are used to being oversold to, with ecstatic reviews, and book blurbs.

Will it make a difference for your book? There is no way to be sure without testing and trying. Invest in an editorial review. Seek out awards to enter and don't hold yourself back by thinking your book's not good enough. Let somebody else be the judge of that.

Hannah Jacobson, Book Award Pro

“When it comes to winning prestigious awards, the challenge for self-publishing authors is twofold,” says Hannah Jacobson, ALLi's new Awards Advisor and founder of ALLi Partner Member, Book Award Pro. “Awareness and navigation. Firstly, awareness that your book could suit the award requirements; secondly, actually navigating your book through the submissions process, which can be lengthy and cumbersome.

“For example, the Pulitzer Prize openly accepts self-published works. However, many indies are unaware of this openness…and thus never navigate their works through the process. How unfortunate! Lack of awareness leads to no submission, which leads to lack of recognition in these award programs. It is a vicious cycle, but one we can certainly break. Show up, give your book every chance to gain recognition (whether through smaller awards or famous ones), and the literary world will take notice.”

Many significant literary awards are now opening up to indie authors.

These include:

- The Premier’s Literary Awards

- The Arnold Bennett Prize

- The Bord Gáis Energy Irish Book Awards

- The British Book Awards

- The Commonwealth Book Prize

- The Rathbones Folio Prize

- The Jhalak Prize

- The Lambda Literary Award

- The Peters Fraser + Dunlop Young Writer of the Year

- The Pulitzer

For more on submitting to awards, we have three useful resources.

For more on submitting to awards, we have three useful resources.

- ALLi's awards rating page (currently being updated)

- ALLi's Ultimate Guide to Winning Book Awards: Tips and Tools (blog post)

- ALLi Prizes for Indie Authors, our short guidebook, packed full of tips and advice for preparation and submission. ALLi members can download a complimentary ebook copy of Prizes for Indie Authors in the Member Zone. Navigate to allianceindependentauthors.org and log in. Then navigate to the following menu: BOOKS > SHORTGUIDES. Other formats are available to members and non-members in ALLi’s Bookshop

Prestige in other forms can give you a leg up in this category too, says Melissa Addey.

Consider MAs and PhDs. You can even get a studentship for a PhD in Creative Writing, which in the UK means you get paid approx. £17,000pa (and all your fees paid) for 3 years. A ‘full-time' PhD actually takes up about 2/3 full-on days plus some thinking time per week.

Or writer residencies in prestigious places is another option. I was one for the British Library, which opened many, many doors for me. Try to align yourself to some high-level institutions Also grants from prestigious funding organizations, the chance to lecture at a university or well-known educational establishment can all boost your profile and help you to reach the right readers.

It takes research, a lot of applications and some practise, but there is definitely a spiral of success that happens, whereby people don’t want to be the first in line to give you a grant/opportunity, but want to join in once someone else has!

Consider targeting literary festivals where literary fiction takes prime focus. Again, don't assume they don't welcome indies, many do. For example the very prestigious Hay on Wye, which has multiple events in the UK, Peru, Spain, Columbia, Mexico and Texas, is open to indie authors. Check out our resources on the Open Up to Indie Authors campaign page (log in needed)

Research their themes and styles, then pitch yourself as a speaker, workshop facilitator or as part of a panel.

Marketing for Self-Publishing Literary Fiction Authors

What, then, is the best way for a self-publishing literary fiction author to market and promote their books?

Literary Fiction Covers

As in every other genre, covers are crucial and your cover should be the very best you can buy. Melissa recently had an author lament that no-one reads their books because they are too literary.

“I read one of the books and actually, it would appeal more broadly because although it is very well written and literary it is also engaging, but its cover is almost deliberately off-putting to a wider audience. It looks like a really ‘classic’ textbook that you’d be set at school and some people are going to be very turned off by that. Have something that looks like thought went into it … but don’t assume there might not be a bigger audience than you’re giving readers credit for.”

As it's common for literary fiction releases to be slower, try and keep an eye on current trends. With slow releases, a new cover can make readers feel this is a new and interesting read (Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall trilogy was fully re-covered as each new book came out, to match the current trends around the time of each publication date).

Roz Morris, literary fiction author says,

“I’ve come across many literary indies whose covers are letting them down. They want to be taken seriously and I've tried to kindly suggest they could present their work professionally – and they reply that the quality of their words is all that matters. But literary novels have to communicate a well honed aesthetic sense. Nuance is everything. A terrible cover will send the message that the writer has no sensitivity. If anything, the covers for literary fiction have to be even more polished than genre covers.”

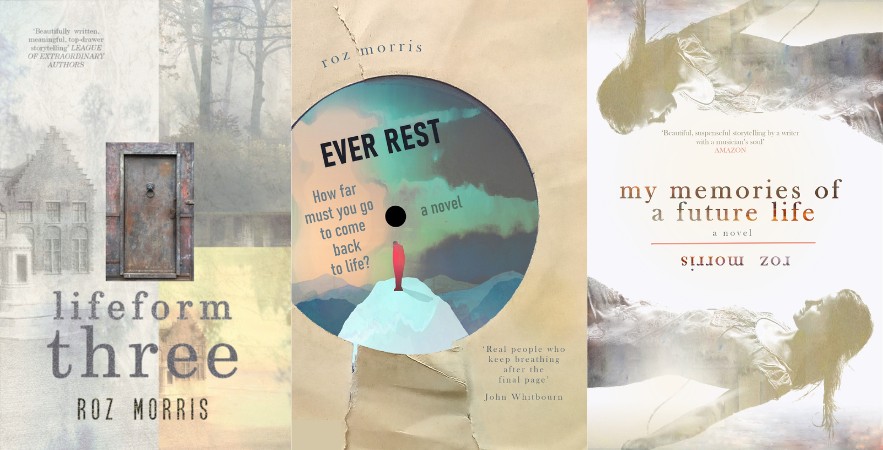

Roz Morris covers, designed by Roz Morris.

Book Descriptions

Use a different kind of blurb: ones based on plots and questions (how will he ever…?) are unlikely to strike home. Depth and complexity should be reflected in the blurbs.

Give a light plot blurb ‘intro’ and then focus on the themes and ideas being explored within the text and the likely emotions or the ‘thought journey’ the reader will experience.

Literary fiction often features characters who are morally ambiguous and possess personal flaws, captivating readers with their intricate backstory and inner psychology. They may even be evil or unlikeable. The blurb should hint their complexities and imperfections are revealed in a nuanced manner, allowing for a deeper exploration of their motivations and faults.

Author Collaborations

Gather a group of authors who also write literary fiction and carefully curate the quality of those books and their covers, so that you are confident that your joint reading community will appreciate this curated list. You can do this via BookFunnel by setting up invite-only promotions.

You don’t need to discount the books, you just all promote them via your own channels saying, ‘perhaps you’d like to explore these books.’ This can get a noticeable and positive response. If you create a group that works, consider planning regular such mentions, especially as members bring out new books. Literary fiction authors often write more slowly and so benefit from keeping attention on their works and having people ready to mention a new launch.

Newsletter swaps or BookFunnel co-promotions would work well here.

Book Pricing Strategies

Consider how you price your work. Readers who like literary fiction may consider very low permanent (no promotional) prices an indicator of poor quality and be put off. Also consider what formats you publish in: offering multiple formats is desirable, as many litfic authors like to read in print and without an audiobook, you can be invisible to younger generations, who like to consume their fiction in audio format.

Ensure that your books can be ordered into bookshops (and mention that on your website). Some literary readers, who tend to be thoughtful folk, pride themselves on not using the larger online retailers.

Conversely, don't assume that other tried and tested indie strategies — free book giveaways — don't work for literary fiction. As we've seen, it's a broad church and not all litfic readers want the same things.

Test and try. Iterate. Improve. Explore and experiment until you hit on what's right for you and your books.

How to Market Literary Fiction: Roz Morris Case Study in Newsletters

Roz Morris is a novelist, memoirist and writing coach. She’s taught masterclasses at international events and for The Guardian in London. She’s a story consultant for a thriller publisher in Dublin and a regular panelist on the Litopia YouTube show Pop-Up Submissions, with literary agent Peter Cox. She’s acclaimed for her own novels: My Memories of a Future Life, Lifeform Three (longlisted for the World Fantasy Award), and Ever Rest (finalist with honourable mention in the Eric Hoffer Book Award) . She’s also the secret hand behind ghostwritten books that have sold more than 4 million copies. Find her on her website, her newsletter and you can tweet her on @Roz_Morris

Roz Morris, ALLi Magazine Editor

Q. Does advertising work for literary fiction?

I’ve tried advertising but never got much traction. Literary is a broad category and the competition is too rich for me.

I could advertise in niches for the subject of each book, but I’ve found that to be ineffective because subject niches are quite literal. For instance, one of my novels features a dual timeline and other incarnations. If I advertise in those subject areas, readers tend to want a traditional treatment, not a quirky story with an unconventional take.

I’ve found the best marketing tool is myself. If I speak at an event or on a podcast, or if I hold a book-signing, I sell books. I can involve people in what I write and what I’m interested in, and that personal touch seems to do the trick.

Q. How can indies translate that to a bigger audience?

I use my newsletters. I used to be wary of newsletters as a marketing tool, but now I love them.

To start with, I was put off by the standard advice – to offer giveaways, previews, special offers, bonus chapters and so on. Much of that is impractical for me. I have a small catalogue, so giveaways would soon bleed me dry. If I wrote about the next book I hoped to have on sale, I’d be writing the same update for years. ‘Did a bit more this month. It’s coming along. It’ll be finished, oh, I don’t know when.’ Readers would get mighty tired of that.

So for a long time, I thought I couldn’t send a newsletter because I wouldn’t have news.

Things changed when I found myself writing a literary travel diary, Not Quite Lost. It was an unexpected thing and I wrote a newsletter to explain, including why I had doubts, because who would be interested in my diaries? Several subscribers wrote back cheering me on. It was the most personal newsletter I’d ever written, and they liked it. I suddenly saw. I could write about life between launches and book events – as a 24/7 creative person.

I now send a newsletter every month, and only a small part of it is works in progress or sales stuff. The rest is personal adventures that arise from books I’ve written, adventures that might end up in future novels or memoirs, books I’ve recently loved and want to share, creative friends I want to celebrate. I wrote about a highway I used to drive on that had been returned to nature – continuing the spirit of my travel memoir. I wrote about meeting a friend from my teen years and discovering how we had both turned into professional creators.

The essence of it is connection, as it is when I’m able to present my work in person.

Is it effective? That’s impossible to measure. Some people unsubscribe, but who doesn’t get unsubscribes? Some write back every month and continue the conversation, or just say they enjoyed it.

Q. How do you attract new subscribers?

I have design experience so I create graphics for each edition of the newsletter, which I share intensively around my socials. I use them as headers, changed each month, on my Facebook page, Tumblr and Linked In, so people can see what I’ve been doing recently. They’re also in my email footers and at the end of every post on my blog. When new people sign up, I have a welcome sequence that explains who I am and what I’m about. People write back to that too. It certainly seems to generate a sense of connection.

Q. Do you use lead magnets to attract new subscribers?

I don’t use them myself. Some literary writers offer short or flash stories as an incentive, but short form is a discipline of its own and not all novelists find it natural. I don’t, and anyway, short form fiction wouldn’t be a faithful showcase for my work.

That’s a crucial point – whatever you offer, whether through a freebie or the newsletter content itself – should be true to the books you write. That’s the relationship you’re building.

Above all, it’s important to own your identity as an artist. Know what’s true to you and what isn’t.

And know that your work has value in itself. A lot of writers think the only thing they have to offer – if they can’t give special deals – is advice for other writers. I made that mistake myself, thinking my own work had to take a discreet and embarrassed back seat. (Although I’m also an editor and writing coach, so writing advice is not entirely irrelevant.)

But much of conventional newsletter theory asks what value we are offering to readers. If your newsletter is a good read, and interesting to the right people, that is value. And the literary crowd, more than anybody, appreciates the writer who has a mind they enjoy.

You don’t need extra offers or bells and whistles and bribes. Take the long view and be yourself.

I am a UK-based British author. Of the awards noted, my books would only be eligible for the Rathbone award. However, it’s important to note that you can’t nominate your own books for the Rathbone. Books are nominated by members of the Academy. Each member can nominate up to three books. The way in would be to court a member of the Academy and persuade them that your book was worthy. I imagine that unless you’re lucky enough to know an Academy member, it is quite a closed world!

Thanks for this dose of reality!

Yep. The British Book Award has a criteria of already successful, so that’s little help when you’re trying to make a breakthrough. I’ve tried entering a book in the Booker (one I published for someone else) and the criteria are really stacked against small indie publishers – the qaulity of the book is irrelevant. The big publishers maintain their fortress walls.

Hi Steve, With the British Book Awards, Self-Published Titles is a category all of its own. However, the award is for book design and production rather than the quality of the writing . ‘The judges will be looking for exceptional design,

free of typographical errors, with particular emphasis given to excellent layout and standards of typography.’ It is a completely different slant than other awards.