My guest this week is Phyllis Cole-Dai, whose work spans topics as disparate as homelessness and the plight of American Indians. For Phyllis, here's what they all have in common. She is able to totally immerse herself into these topics that tend to divide us and come back with stories about how they impact individual humans. If we see individual people, learn their stories, then maybe we can all find common ground in these divisive times.

Every week I interview a member of ALLi to talk about their writing and what inspires them, and why they are inspiring to other authors.

Every week I interview a member of ALLi to talk about their writing and what inspires them, and why they are inspiring to other authors.

A few highlights from our interview:

On Writing About Homelessness

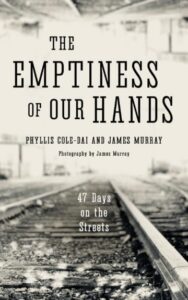

And I was accompanied by a good friend named James Murray and after 24 hours of being on the streets, we were already so traumatized and shattered that we thought it would be wise for us to begin taking notes and prepare ourselves to do a writing project once we came off the streets that could serve as a window for the reader onto what can happen to a person when they are without a home.

On Why She Wrote About the US Dakota War

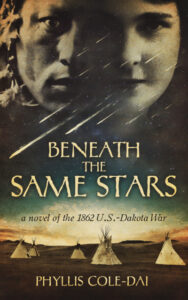

And so as I began to hear about this history, it struck me that many of the dynamics that were in play and contributing to that uprising in 1862 are still with us here in this region today, you know, things like government corruption, lack of respect for tribal sovereignty, competition for scarce natural resources, all kinds of things, you know, forced assimilation. And so I thought, if I try to write about this war in a way that captures people's imaginations, it might be a good way to provoke discussion about our contemporary situation

Listen to my Interview with Phyllis Cole-Dai

Don't Miss an #AskALLi Broadcast

Subscribe to our Ask ALLi podcast on iTunes, Stitcher, Player.FM, Overcast, Pocket Casts, or Spotify.

Find more author advice, tips and tools at our Self-publishing Author Advice Center: https://selfpublishingadvice.org, with a huge archive of nearly 2,000 blog posts, and a handy search box to find key info on the topic you need.

And, if you haven’t already, we invite you to join our organization and become a self-publishing ally. You can do that at http://allianceindependentauthors.org.

About the Host

Howard Lovy has been a journalist for more than 30 years, and has spent the last six years amplifying the voices of independent publishers and authors. He works with authors as a book editor to prepare their work to be published. Howard is also a freelance writer specializing in Jewish issues whose work appears regularly in Publishers Weekly, the Jewish Daily Forward, and Longreads. Find Howard at howardlovy.com, LinkedIn and Twitter.

Read the Transcript

Phyllis Cole-Dai: Well, hi, Howard, and everybody who's listening. I'm Phyllis Cole-Dai and I'm speaking to you from Brookings, South Dakota. I've lived here for almost 20 years now. I'm originally from farm country in Ohio, which is still home, but I've lived here long enough now that it feels like my second home.

Howard Lovy: Phyllis was born in a small community to farmers. But she was fortunate that her parents and teachers saw that Phyllis was a little different and encouraged her interest in writing.

Phyllis Cole-Dai: Oh, I dreamed about it from the time I was a little one. And I had teachers from, I think, second grade on who were taking a special interest in my writing and really encouraging me. And that was pretty unusual because I was growing up in a very small rural school district.

But we just had fabulous teachers, at least that's the way I experienced them. My parents noticed in early elementary school that I was already dreaming about being a poet and a fiction writer and so they gifted me with my dad's old manual typewriter, you know the kind that doesn't plug in – a very musical sensory experience typing on that typewriter with the clickety-clack and the bell at the end of the line and everything.

That was when I first started taking my writing seriously, I think, because they honored my dream and you know, they were farmers. They had neither graduated from college. They didn't know a lot of writers, maybe none at all. For them to really invest in my dreams was was important. And to this day with my author branding, I use a lot of old manual typewriter images as a way of thanking them and also thinking that old typewriter.

Howard Lovy: That old typewriter went everywhere with her as she honed her writing craft as a child, and through college and her travels.

Phyllis Cole-Dai: I went to a college named Goshen College which was just a fabulous, fabulous liberal arts school in Goshen, Indiana. And they required at that time of all their students that we leave the United States for a trimester, a period of three and a half months to do study and service work in another country. And so I ended up going to the recently established nation of Belize, which was just coming into independence from British rule. And so I spent part of my time in the capital city of Belize City and then the rest of my time I was in a native mixed heritage village near the mountains. And it was just an amazing eye-opener for a farm kid from Ohio.

Howard Lovy: It was also Phyllis' first experience with an Indigenous culture, knowledge that she filed away for possible future use. Meanwhile, Phyllis convinced herself that writing was not going to be a career. So she decided to study to become a minister. But it turned out that wasn't for her either.

Phyllis Cole-Dai: Because I was convinced, as many people are and as many people experience, that I would not be able to support myself by my writing. And so I went to seminary to study to become a United Methodist minister. And while I was there, I was exposed to Buddhism and a lot of other world religions and realized that I was too much of a heretic to become a minister. And so I after graduating with a master of theological studies, and doing a lot of liturgical writing for the church before I sort of went a different way, I then went to the Ohio State University to get a masters in creative writing, and also in folkloristics.

And so that's kind of where I learned that I didn't belong in academia and I met my soon-to-be husband. And he was a scientist, still is. And when we got together, we kind of went through some experiences that that made us realize that I was going to be happiest if I could be a creative person, free of financial concerns. And so we decided together to live frugally on his income and whatever else I could bring in through my creative endeavors. And that's when I began to write in earnest.

Howard Lovy: But it wasn't until much later that Phyllis found something that moved her enough to write a book. She and her husband were living in Columbus, Ohio and always after a human story, she found an intolerable amount of human suffering around her.

Phyllis Cole-Dai: At that time, I was living in Columbus, Ohio with my husband and had been living there for more than a dozen years and Columbus at that time, the 15th largest city in the United States, and it was an absolute boom town, but like all boom towns, it had a shadow side, including a sizable and growing homeless population. And I could see this population kind of exploding and didn't know what to do about it because this disparity between, you know, the wealth in the city, and the situation for homeless people was just unconscionable to me.

So I just started asking myself “What is it that I might do about this?” And after a period of some months, the answer came, I talk about it as the Thing, with a capital T, came down and let me know that I needed to go live among them for a period of time and just try to be a compassionate presence among them. And so I went out for 47 days, that period of time coincided with the Christian observance of Lenten Holy Week, which was a rich spiritual backdrop for what I was doing.

And I was accompanied by a good friend named James Murray and after 24 hours of being on the streets, we were already so traumatized and shattered that we thought it would be wise for us to begin taking notes and prepare ourselves to do a writing project once we came off the streets that could serve as a window for the reader onto what can happen to a person when they are without a home.

Now, James and I were not homeless. We could have ended this at any time; we were there by choice, but even though we were there by choice and had every advantage, we came home from that experience a real wreck and it took us years to, I won't say recover, but to move into a new normal because we had been changed so radically by the experience.

Howard Lovy: The book is called The Emptiness of Our Hands: 47 Days on the Streets. What Phyllis hoped to accomplish in the book is something more than a chronicle of an idea called homelessness. She wanted to move it out of the abstract and place on it a human face

Phyllis Cole-Dai: Well, it's now in its third edition. It keeps selling, you know, and I do a lot of speaking on it. I didn't think that now 20 years after these events, that I would still be doing that, but unfortunately, the situation for homeless people in this country has not substantially changed. There have been some improvements.

But really, I think the book is also just a book about humanity and about how we relate to one another. We don't need to treat homeless people differently from the way we treat the person next to us in the line at the grocery store, or the person that we're sitting across from at the Thanksgiving table. I think the book kind of transcends the quote unquote issue of homelessness and it talks about how we can be present to one another in our daily living.

Howard Lovy: And part of being present is engaging in what is called mindfulness practices, which Phyllis found necessary in order to recover from the trauma of experiencing homelessness. And that became her next project, editing an anthology of mindfulness poems called Poetry of Presence.

Howard Lovy: And part of being present is engaging in what is called mindfulness practices, which Phyllis found necessary in order to recover from the trauma of experiencing homelessness. And that became her next project, editing an anthology of mindfulness poems called Poetry of Presence.

Phyllis Cole-Dai: This, among other therapies, helped me overcome a lot of the panic attacks and other difficulties I was having when I came off the streets. So I started reading poetry that has sort of a mindful quality about it during that period of recovery and eventually, I started a blog called A Year of Being Here, which presented a mindfulness poem and a companion piece of art every day for three years. That was an amazing experience. It was a free service, and we ended up with thousands of subscribers all around the world and it told me there was a real hunger for this kind of poetry.

So eventually, I asked my friend Ruby Wilson, who is a poet, I don't consider myself a poet, ny the way, I'm a reader of poetry and I asked her if she would help me to edit an anthology of mindfulness poems, and that resulted in Poetry of Presence: An Anthology of Mindfulness Poems that was published by Grayson Books and it has done remarkably well. It's an award winning anthology and has sort of taken on a life of its own.

A lot of people who are in the helping professions use it for sustenance, not only for themselves, but for the people that they're helping. But they also have teachers, writers, poets, all kinds of people who are making use of it and we just love to hear stories about how people are finding sustenance from that book.

Howard Lovy: Phyllis' next project that brought her the human stories she sought came when she moved to South Dakota, and immediately was surprised that the anti-native bigotry she encountered.

Phyllis Cole-Dai: Well, it began when my husband and I flew into Sioux Falls to look for a house when we were getting ready to move here and I looked out the plane window and it was the middle of March, we were in the middle of a snowstorm up here. The snow was everywhere down below and there were scarcely any trees. And I knew right away coming from the woodlands that I was moving into a very different geographical landscape than I had ever encountered before.

We met a realtor after we got off the plane, and within an hour, that realtor who was a white person told us a racist joke about American Indians, you know, just had to make the assumption that it was okay based on my skin color. And so then I knew I was moving into a very different cultural landscape. So I knew that I needed to start educating myself about this landscape that I was in and I started studying about the native cultures who are sharing this landscape with us, who have settled here now, especially the Lakota, Nakota and Dakota peoples who make up the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ.

And still, even though I was studying about these cultures, it wasn't until 2012 that I first heard about the US Dakota War of 1862, which is also sometimes called the Sioux Uprising or the Dakota Conflict. That was the 150th anniversary year of the war, marked by many public commemorations, especially in Minnesota, right next door, basically just a 20 minute drive from where I live. And so as I began to hear about this history, it struck me that many of the dynamics that were in play and contributing to that uprising in 1862 are still with us here in this region today, you know, things like government corruption, lack of respect for tribal sovereignty, competition for scarce natural resources, all kinds of things, you know, forced assimilation.

And so I thought, if I try to write about this war in a way that captures people's imaginations, it might be a good way to provoke discussion about our contemporary situation so that perhaps we can make a different kind of future possible working as good partners with native people in this region. So that was my hope and it's a grandiose hope, but I tried to do my little part, you know.

Howard Lovy: The result was her historical novel called Beneath the Same Stars, a Novel of the 1862 US Dakota War. She chose to write it as fiction because it was a way to dig deep into the emotions and humanity of a dispute. The way she can contribute is by telling a story rather than reciting dates and names.

Howard Lovy: The result was her historical novel called Beneath the Same Stars, a Novel of the 1862 US Dakota War. She chose to write it as fiction because it was a way to dig deep into the emotions and humanity of a dispute. The way she can contribute is by telling a story rather than reciting dates and names.

Phyllis Cole-Dai: I wanted to take us into the heart of the story, I wanted to delve beneath jockeying facts and opinions to get us down into the feelings of things. And so I focused on an actual person named Sarah Wakefield who got caught up in the war and her relationship with her Dakota captor, whose name was Ćaske, that means firstborn son, his spiritual name was Wicanhpi Wastedanpi, which means something like “he who is liked by the stars.” Their relationship ship became a source of great controversy and ultimately, tragedy. So it was a wonderful vehicle, and a sad vehicle through which to view the events that I'm writing about.

Howard Lovy: Through hard hitting nonfiction involving homelessness, mindfulness, poetry, and an epic history, there really is a theme throughout Phyllis' work. It's about how to deal with things that divide us and bring us back together. Not a trivial thing to do these days. And the way to do it is through the power of story.

Phyllis Cole-Dai: I guess I'm an idealist at heart. You know, I want my writing to contribute somehow to something positive in the world, to help build community rather than to tear down There's so much need for that, I think, especially right now, not just in our country, but in countries around the world. And so I think from the beginning of my writing, I have always wanted to try to help people empathize with one another. The other thing that my work has in common is story.

Every genre that I work in has that kind of story grounding there because I think it's primal. You know, we've been telling stories to one another since we've had language. And we we go to a different place in our spirit, I think, when we listen well to each other. And my job as a writer or as a composer, as an editor is always to try to make the conditions ripe for people to hear, to listen, and then I can't take responsibility, you know, for what the reader or the listener brings, but I know that the magic of story can work on them if they're open.

You know, I want my writing to contribute somehow to something positive in the world, to help build community rather than to tear down There’s so much need for that, I think, especially right now, not just in our country, but in countries around the world.

Because of my skin tone, the white realtor who made the offensive joke about American Indians merely assumed that it was alright to do so. I suddenly realized I was entering a very different cultural environment.

I base every genre I write in on this type of story, as I believe it to be primordial. We’ve been telling each other stories ever since we’ve had language.