ALLi Partner member Richard Bradburn helps indie authors handle hyphens without mishap

Today the ever-dashing ALLi Partner member Richard Bradburn, professional editor and managing editor of editorial.ie, shares top tips on the effective use of hyphenation in our self-published books, employing some amusing examples.

Today I'm going into hyphenation in detail:

- why we hyphenate words

- what guidelines exist for hyphen usage

- how word structure continues to evolve around hyphens

Why do we hyphenate anything?

Let’s get one specifically utilitarian use of hyphens out of the way first…

Typesetting

In professionally printed text, justified to both margins, words sometimes need to be split to avoid bizarrely exaggerated word spacing.

Where words are split is a pretty major topic in itself. It’s usually common sense. It would be unusual to see a very short word split. Usually a typesetter/layout designer can avoid this happening.

A lengthy word can usually be split easily by syllable, ending in a consonant. So, for example, that would be con‑sonant. Why is it not cons‑onant? Because “con” is a distinct syllable, and “son” is another distinct syllable. That’s an over-simplification and, as a professional editor, I actually have a dictionary whose sole purpose is showing me where words should split (dull reading, but, hey – it’s tax deductible). Most writers can rely on their publisher, or word-processing program, to do the dirty work for them.

Forming compound words

This is where the fun starts!

The usual need for a hyphen is in forming a compound word. That word can be a compound noun, verb or adjective.

The reason we hyphenate is for clarity, and this is an over-riding factor.

If you don’t need a hyphen, there’s no need to put one in.

Where some ambiguity arises without a hyphen, then there’s a need to use one. Consider the first half of a sentence, “Twenty year old girls”. Twenty toddlers celebrating their first birthday? No, because the sentence continues “can abuse alcohol”. Hyphenation makes the meaning clear. “Twenty-year-old girls can abuse alcohol”. Another example: “I’d like to recover the sofa”. One wonders what happened to the sofa? Was it stolen? Did it fall down a well? Hyphenation clarifies the meaning; “I’d like to re-cover the sofa”.

Compound nouns

Compound nouns are generally pretty straightforward. They will be listed in a good dictionary (although check that it’s up to date – hyphenation evolves, as I’ll mention later). They can be closed up, “toothpaste”, open, “ice cream”, or, rarely, hyphenated, “city-state”. How they are written generally depends on current usage, and if you’re not confident, best and quickest just to look it up.

Compound verbs

Compound verbs are also generally straightforward. They can be closed, “to breastfeed”, hyphenated, “to court-martial”, or, in the case of what are properly known as phrasal verbs, open, “to break in”. Again, these should be listed in a reliable dictionary, as long as it’s up-to-date.

Compound adjectives

The basic rule is: hyphenate if it comes before the noun to which it relates, open if after.

So, “a quick-thinking fireman”, but “the fireman was quick thinking”. Why is that? Well, “a quick thinking fireman” might be a particularly fast fireman who happened to be thinking. What’s important is that his thoughts were quick. This ambiguity doesn’t exist where the adjective is used after the noun.

The main exception to this rule is where one component of the compound is an adverb. This can be a word ending in –ly, “the quickly deflating bouncy castle”, or another adverb, like very, “a very large cake”, or much, “the much admired pianist”.

Prefixes

Use a hyphen to join a prefix to another word, like “post-apocalyptic”. However, here usage is changing. More and more commonly, words that used to be hyphenated are closed up. Consider “co-operate”. Some diehards still hyphenate co-operate, but most writers now close this up to cooperate even though the prefix ends with the same vowel the other word starts with. In the days when the rules of hyphenation were more rigid, this would definitely have been frowned upon.

Evolution

I mentioned at the outset that hyphenation is one of those areas of the language that is constantly evolving.

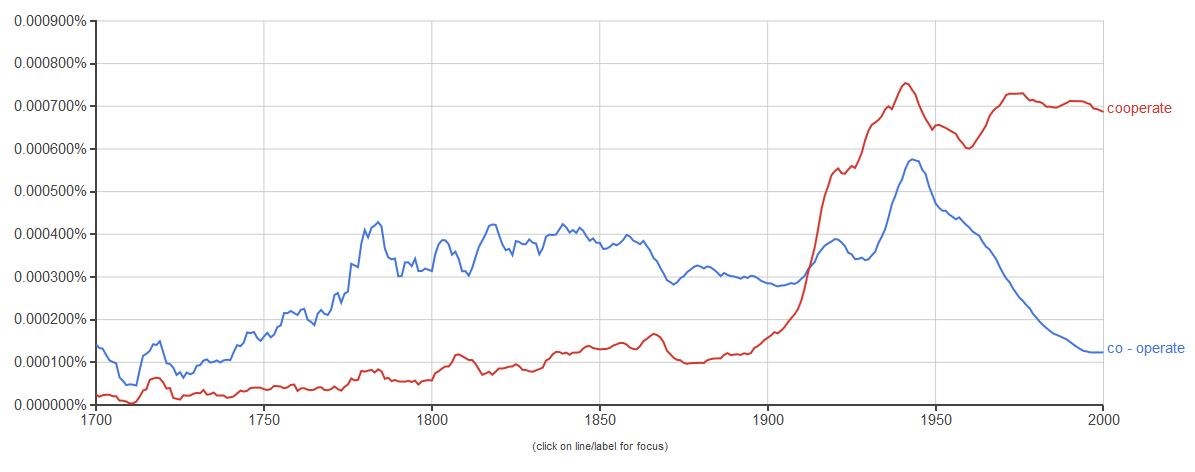

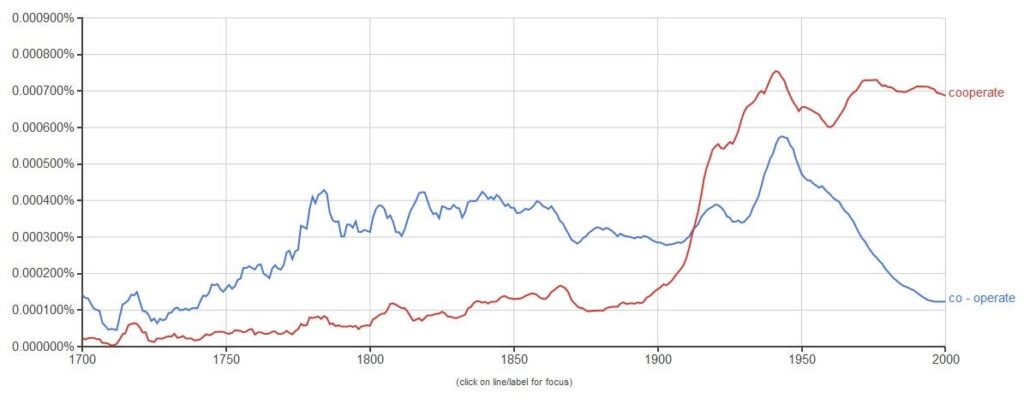

Taking our example of cooperate above, if we look at a Google Ngram of the word, we can see clearly that the closed up version began to gain the ascendancy in the early 20th century, and is now in the distinct majority.

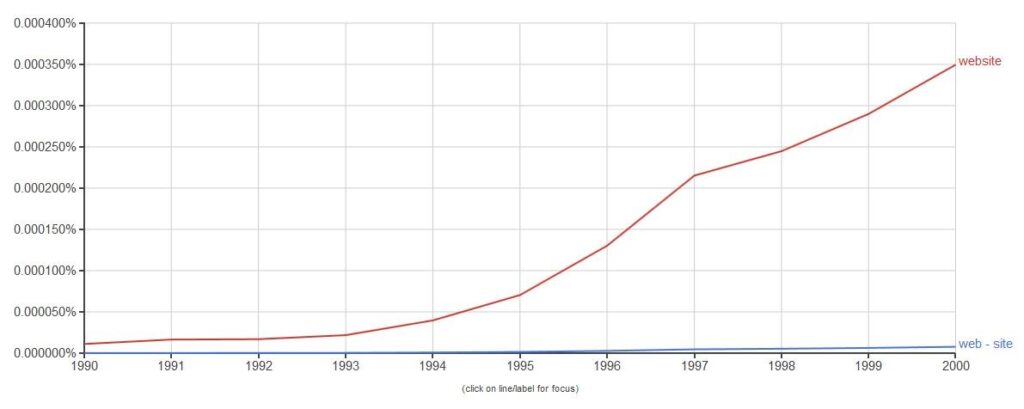

That evolution took place over a couple of centuries (around 1720 no-one said “cooperate”). But modern words evolve even faster. Look at an Ngram of website.

“Website”, all one word, has always been more popular than the hyphenated version, but now it’s vastly more common.

The only way to make sure that your compounds are up to-date is to check with a dictionary, or, if you’re really keen, to check with a style guide such as the Chicago Manual of Style (CMoS).

The hyphenation table of the current version of CMoS runs to nine pages and includes things beyond the scope of a short blog post, like compass points (“northeast”, but “east-northeast”), proper nouns (“African American” but “Franco-Prussian War”) and dozens of prefixes.

Even the CMoS style guide, which is updated annually, quite often redefines current usage, so there are few constants. There are some strange outliers in real life. The editorial style guide for the New Yorker magazine, for example, insists on hyphenating “teen-ager”.

Rather than worry too much about it, especially in fiction, try to adhere to one particular usage.

Don’t say “homemade jam” in one chapter, and “home-made pickle” in another. It’s very easy to make a mistake, especially if those terms can occur chapters apart.

Have you been paying attention? One compound word in this blog is spelled in no less than three different ways. A good editor should have noticed!

#Authors and #editors - are you hyphenating in all the right places? And what are the right places anyway, when the English language keeps evolving? Professional #editor Richard Bradburn of @editoreditorial offers advice and… Share on XA COMPANION PIECE ON CORRECT USE OF DASHES

From the ALLi Author Advice Center Archive