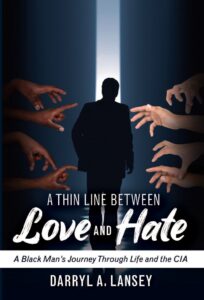

My guest this week is Darryl Lansey, who has a kind of love/hate relationship with his former employer, the US Central Intelligence Agency, the CIA. As an analyst and adviser to presidents, he loved making a difference for his country. As black man, he hated the institutional racism that was baked into the organization. He writes about his experiences in his new book, A Thin Line Between Love and Hate: A Black Man's Journey Through Life and the CIA. I spoke to Darryl about his experiences at the CIA.

Every week I interview a member of ALLi to talk about their writing and what inspires them, and why they are inspiring to other authors.

A couple of highlights from our interview:

On Racism in the CIA

I was angry, but more disappointed, and I was disappointed because I had a bit of a naivety early in my career. I thought that I was hired to do a job and, it was clear to me that the individual, my supervisor, who was looking at me across the desk, didn't value me as a person, let alone what I was offering.

On the Future of the CIA

What inspires me and what gives me hope about the agency is, I think there are individuals of this current generation who are much more open to the idea of diversity and inclusion as being part of just the day-to-day environment that they're in.

Listen to my interview with Darryl Lansey

Subscribe to our Ask ALLi podcast on iTunes, Stitcher, Player.FM, Overcast, Pocket Casts, or Spotify.

On Inspirational Indie Authors, @howard_lovy interviews retired CIA analyst Darryl Lansey, who tells of the institutional racism baked into the organization and what he did about it. #indieauthors #memoir Share on XFind more author advice, tips and tools at our Self-publishing Author Advice Center: https://selfpublishingadvice.org, with a huge archive of nearly 2,000 blog posts, and a handy search box to find key info on the topic you need.

And, if you haven’t already, we invite you to join our organization and become a self-publishing ally. You can do that at http://allianceindependentauthors.org.

About the Host

Howard Lovy has been a journalist for more than 30 years, and has spent the last eight years amplifying the voices of independent publishers and authors. He works with authors as a book editor to prepare their work to be published. Howard is also a freelance writer specializing in Jewish issues whose work appears regularly in Publishers Weekly, the Jewish Daily Forward, and Longreads. Find Howard at howardlovy.com, LinkedIn and Twitter.

Read the transcript of my interview with Darryl Lansey

Howard Lovy: My guest this week is Darryl Lansey, who has a kind of love/hate relationship with his former employer, the US Central Intelligence Agency, the CIA.

As an analyst and adviser to presidents, he loved making a difference for his country. As a black man, he hated the institutional racism that was baked into the organization. He writes about his experiences in his new book, A Thin Line Between Love and Hate: A Black Man's Journey Through Life and the CIA.

I spoke to Darryl about his experiences at the CIA. Well, as much as he was allowed to reveal.

Darryl Lansey: Hi, I'm Darryl Lansey. I'm originally from Baltimore, Maryland. I'm a recent retiree, within the last two years, of the Central Intelligence Agency. I spent nearly 33 years there.

Howard Lovy: And just tell me if I'm asking about classified information where you'll have to shoot me if you tell me.

Darryl Lansey: Yeah, in fact, I will hue very closely to the book and what's been approved by the agency's publication review board.

Howard Lovy: Well, let's start from the beginning. Tell me where you grew up in Baltimore and what kind of environment that was.

Darryl Lansey: Sure. So, I grew up in Baltimore, Maryland on the west side, and if anyone's familiar with the HBO show The Wire, that's essentially the neighborhood that I grew up in, and I grew up primarily in the 1960s and seventies.

So, my reflections on Baltimore are primarily as a child and as a teenager, but my mother remained in Baltimore until her passing in 2014. So, I would continue to go back to my neighborhood and see old friends and family.

West Baltimore, where I grew up, is predominantly a black community. I grew up in a working class, black family. My neighborhood was primarily working-class blacks, poor to the lower middle-class blacks. My upbringing, my mother was a schoolteacher, and she was very much into education and making sure that my two brothers and I got a good education. My father was equally big on education, but as I described in the book, my father dropped out of high school in 11th grade.

And so, as I like to tell people, my mother really was the one who emphasized education while my father spent a lot of time focusing on making sure that we had common sense to survive in the world. My upbringing, I spent the early part of my childhood going through Baltimore city public schools.

I had what I describe as a life changing event in 1972. Originally, I was asked if I had any interest in going out to a private school in the County to participate in a Saturday tutorial program, and I said, yes. That program was every Saturday, and I would go out on a little bus out to the County to be tutored.

And I did that for two years, my fifth and sixth grade. That was a complete environmental change for me. I went from an elementary school that had, it was predominantly black that had, like a lot of urban schools, not a lot of resources, to a day school, a country day school that sat on a hundred acres of land, bucolic setting; trees, pond, where for those two years, I was being tutored and, for the first time, interacting in an environment that was new to me, which was an environment that was predominantly white.

Howard Lovy: That must've been quite a culture shock for you.

Darryl Lansey: It was, but it was a good culture shock, and I was fortunate in my second year, that I had a tutor who said, do you have any interest in going to this school?

And I knew my parents couldn't afford it because at the time it was more than $10,000 a year to go to that school, but the individual gentlemen named Bruce, he set me up to take an exam, a scholarship exam, and that set me on a path of eventually entering that school from seventh through to 12th grade.

So, from seventh through 12th grade had a benefit of a private school education that my parents couldn't afford on their own.

Howard Lovy: So, tell me a little more about Baltimore in terms of race relations when you were growing up, and whether that was an issue for you before, or even after you started going to a predominantly white school.

Darryl Lansey: So, Baltimore, and where I grew up in West Baltimore, and I describe it in my book, my interactions with the white world, world of beyond my neighborhood, came in different layers. So, my next-door neighbor, actually was a grocery store and it was owned by a couple, Mr. George and Ms. Mary and their son, David. And Mr. George and Ms. Mary were Polish immigrants who had survived the Holocaust. And I knew nothing about the Holocaust at the time, but I interacted with them whenever I went into the grocery store and played with their son, David.

The only other interactions within my community, as I described it in the book, were the merchants at the local supermarket, but more regularly was the police that would occasionally come into the neighborhood and the interactions with the police officers, primarily as an observer, entering the neighborhood as they were either pursuing drug busts, there was drug activity in my neighborhood.

But the bottom line is, my interactions early on in my life were very limited interactions with the white world and very limited. It wasn't until I entered my private school, the park school, which I describe in the book that my view or interactions with the white community expand. And it was interesting cause my interaction within my own neighborhood, my day school, the private school I went to, started very early in the morning and ended late in the afternoon. My friends and kids that I hung out with, they knew where I was going to school and they would occasionally tease me as I describe in the book on terms of, why are you going to that white boy school?

And also, I describe in the book an incident where I made the mistake one day, actually, my first year, in the seventh grade, and one of my friends three years older than me said, what grade are you in? I made a mistake in seventh of pronouncing the T and H, and he looked at me and he said, who the F do you think you are? You can't speak like the rest of us “N-words.”

Howard Lovy: So, you learned to travel between both worlds?

Darryl Lansey: Yeah, I learned to travel between both worlds. It's often referred to as code switching. So, as I describe in my book, one of my favorite movies is Cool Hand Luke, and there's a line from Cool Hand Luke where the warden says, what we have here is a failure to communicate.

And so, whenever I went to school in the morning, from early morning until 4:30 in the afternoon, I made sure, as my father would repeatedly tell my brothers and I, make sure you speak with the King's English. I made sure I was able to speak with the King's English during the day, and when I came back in my neighborhood at night, I was able to transition back into my neighborhood, more colloquial speaking. That was survival. Without that, I don't think, frankly, I would've been able to progress to where I am today.

Howard Lovy: So, what happened after that? You went off to college?

Darryl Lansey: So, I went off to the University of Delaware on a mechanical engineering and aerospace engineering scholarship. I quickly realized, by my sophomore year, that engineering was not for me, and I had to find another major. So, I transitioned into a double major in geography and geology, and when I transitioned to geography and geology, I actually found a major that actually resonated with me because, at least at the University of Delaware, engineering students really didn't get their hands on until their junior and senior year.

However, as a geography and geology major, I was immediately out in the field collecting rocks, collecting fossils, tasting rocks, because that's one of the ways you tell some rocks mothers, or minerals mothers, is actually taste them.

Howard Lovy: So, you're over there studying geology and geography, you're tasting rocks and you found your calling, you think.

And then somehow, during your graduate work, the CIA came calling or you came calling to them. How did that come about?

Darryl Lansey: A classmate of mine was across the hall from where I was in the dorm who had applied to the CIA, and I happened to be talking to him one day about his process, and just so happens the CIA came on campus at the University of Delaware. I got up early that morning and I was the first person in line, and I was interviewed for the job. I actually didn't think I was going to get called back for further interviews because, during the interview, the gentlemen at the end of the interview said, well, where do you see yourself in 20 or 25 years? And I said, well, I see myself being the director of the Central Intelligence Agency. And he literally pushed his chair back from the table and he looked at me and he said, well, what makes you think you can do that? And I said, well, if I've got to get out of my bed every morning early, then I have to believe that I can make it to that level someday.

Howard Lovy: Did you have any preconceived ideas about what the CIA was? Did you have any trepidation?

I can't imagine that there were too many African Americans in the CIA. Did you have any feeling that you were breaking new ground?

Darryl Lansey: It's an interesting question. So, at that time, however, I had no sense of the demographics of the CIA and assumed at the time they needed a diverse group of individuals, male, female, and then ethnically and racially diverse. But I didn't have a good sense of what the agency was about. The other thing was I had, like a lot of individuals, I did have a fictional version of what the agency was like, meaning that, you know, I'd certainly seen my share of James Bond films, but I didn't see any, you know, high tech screens and, you know.

Howard Lovy: No cool cars filled with gadgets?

Darryl Lansey: No cool cars filled with gadgets, no domes of silence, or anything like that from Get Smart. It was just a regular office building. It wasn't until I actually joined and became a part of the agency that I got a better sense of the demographics within the agency, as well as, the kind of cool things that it does.

Howard Lovy: Your book contains some elements that we all can recognize, and that's working for a toxic boss.

When did you realize that there might be something wrong with some of the leadership at the CIA?

Darryl Lansey: I was in the fifth year of my career when I encountered the first manager, or supervisor, in my career, who it was clear to me did not respect me as an individual, did not respect what I had to offer as an individual. Because I would sit in meetings with my supervisor and my colleagues day after day and propose analytic pieces to go forward for what were then called the National Intelligence Daily, which was the daily finished reports that would go out to the masses of government employees and bureaucrats who had clearances, as well as another product, the President's Daily Brief that went to the president and a very select small group of individuals. Anyway, I was sitting in those meetings on a daily basis, proposing ideas, and every one of my ideas would get shot down by my supervisor.

But the same idea could be raised by one of my white colleagues a few minutes later and my supervisor would say, great idea, we'll go with that. But it was really there that I realized, there's something different going on here. And with that same supervisor, at the time that the Balkans war was breaking out in Europe, I happened to be working the Balkans account.

I'd been working on the account for a number of months, cut to the chase, the deputy director of the CIA had asked me, and several other analysts, to come up to see him to talk about what we knew about what was going on and what was our analytical line and in terms of where did we see the war progressing and the impact that was going to have on the greater European community, and what role the US could play.

I went to the meeting with the deputy director of the CIA, Admiral Studeman, had a great meeting. He said, great briefing, you guys. Keep me informed. I left that meeting very excited, came back to my supervisor's office, sat down because he wanted a debrief of how things went, and as we proceeded to debrief him, and I went with another analyst who I was working with at the time, as we proceeded with debrief, the supervisor said to me, “Well, I'm glad we sent the right spear chucker for the job.” And I was taken aback, and I paused, and I said, “Excuse me?”

And at that point I didn't hear, frankly, anything else he said. And a few minutes later I excused myself and I went back to my cubicle, and the gentleman who was with me at the time, went to the meeting, he came out to my cubicle and wanted to know what was wrong. And I said, you know, what's wrong is the supervisor just called me a spear chucker, and if you're not aware, that's a racial insult.

Howard Lovy: How did it make you feel at the time? Was it anger, outrage, powerlessness? Was there a feeling that you could do something about it?

Darryl Lansey: I was angry, but more disappointed, and I was disappointed because I had a bit of a naivety early in my career.

I thought that I was hired to do a job and I was hired because, you know, the agency hires a very small percentage of people that it interviews and, it was clear to me that the individual, my supervisor, who was looking at me across the desk, didn't value me as a person, let alone what I was offering.

And that comment that he made was just a culmination of a series of incidences up to that point, most prominently, ignoring suggestions that I had had made. And so, I would say, you know, the disappointment and that, for me, is the word that I would use throughout my career and that less anger, and more disappointment.

Howard Lovy: You say in your book that you have a love/hate relationship with the CIA. You believe in its mission and you were right up there advising the president on the Balkans. That's the top of your field. You must have been proud of your work, but at the same time you had to put up with these racial overtones.

Darryl Lansey: There was, I would say, you know, my wife would even say, a deep love for the organization.

And as I describe towards the end of the book, I always felt like I was a CIA owner, and I used to describe to teams that I led and managed that, from my perspective, you have two choices in this world, particularly when I worked for the agency, you can be either an owner or a renter.

And I always saw myself as an owner of the agency, and what that meant was, I always felt like I had as much responsibility for the organization's success than anyone else, rather than a transactional relationship where I would go to work, you know, collect my paycheck every two weeks and then go home.

As I used to say to members of my team, if you're an owner and I would describe it this way, if you're an owner of a house and you cut a hole in the wall, what do you do? Well, you go out and you go to Home Depot or someplace and you buy a dry wall and you repair the wall. Why do you do that? You repair the wall because one, you want to get rid of the hole, but two, you want to maintain and potentially add value to the organization. If you're a renter, you don't care about the hole, or if you do care, you wait for the landlord to fix it. So, I always saw my role, from the very beginning as an owner of the organization. And so, my disappointment often came, and my love for the organization often diminished, when I felt like my desire for ownership wasn't being reciprocated by the organization and the people within the organization

Howard Lovy: Later in your career, you were training others in leadership. Did that give you an opportunity to try to change the culture of the CIA from within?

Darryl Lansey: It did, and one of the things I pointed out to the deputy director at the time is, people do not leave jobs, people leave their supervisors. And I went on to say a few other things to the point where, frankly, as I described the book, I was making a pain of myself. But through that experience, the deputy director actually pulled me aside when I was promoted, in March of 2004, he said, I got a job for you. I want you to go out and revamp the first line supervisor course. It was in the process of developing the course for the first line supervisors that I really began to think about leadership and management as a set of skills that needed a great deal of practice and reflection to do well.

Howard Lovy: What do you hope, at the very least, people walk away with after reading your book?

Darryl Lansey: That's a great question. Well, one of the questions, I listened to your other podcasts, and you asked a question, you know, what inspires you? What inspires me? And as I thought about this, and thinking about the question you just asked, is the current generation of individuals at the agency and America, and the world in general. When I look at the Millennials, Gen Y and Gen Z, they're growing up in a time in which they frankly look at individuals such as myself and you, I'm assuming, as baby boomers and shake their head and go, “We don't get how you think and why you think the way you think.”

They've always grown up in a diverse world where inclusion was part of their mindset. I don't want to make it too Pollyannaish, but what inspires me and what gives me hope about the agency is, I think there are individuals of this current generation who are much more open to the idea of diversity and inclusion as being part of just the day to day environment that they're in, the day to day way of doing business. I'm hopeful for the future of the organization, because I do know, because I taught many of those individuals, I supervised the managers, that there are individuals who are coming up through the system who understand that, in order for the organization to be at its best, it needs to value and take into account all the perspectives of every individual within that organization.

I also, in my book, I wanted to give, and I say this in the prologue. I want it to give voice to what I, from my perspective had been, an underrepresented voice.

Howard Lovy: Well, that's a good way to end it.

Thank you so much, Darryl, for taking the time to talk to me.

Darryl Lansey: Thank you, and I appreciate you reaching out to me and asking to interview and hopefully I shed some light. I'm interested to see how it comes out and how people react to it.