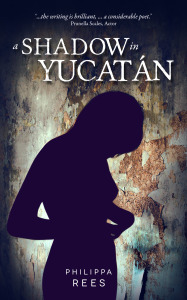

In a moving post about the inspiration behind novels, indie author Philippa Rees describes what triggered her remarkable literary novel A Shadow in Yucatan: an experience so profound that it ultimately made her question whether she could regard herself as the true author of the book.

Why do we write what we do?

A prolific Canadian writer friend accused me (in a kindly manner) of trying to ‘write for immortality'. ‘Nothing lasts, except you' he said. I think he hoped to persuade me to make my life easier, and write forgettable vampire books that might have a hope of readers. So why did I republish a modern Under Milkwood after it had languished unread for eight years? Was life not difficult enough?

Let me take you back to its genesis so you might understand this resurrection of a favoured child.

The Story Behind the Story

In 1969 I was living is a windblown shack on a desolate beach in Yucatan with two children, both under four, sleeping in a hammock and keeping a bottle by my ‘bed' that I could smash against a wall as a weapon in an emergency. There was no electricity, but a Stygian darkness after sundown. The bottle also held a single candle. My nearest and only neighbours were members of the Tonton Macoute, the Haitian henchmen of Papa Doc Duvalier, known for easy murders, gang rape (and voodoo). I was hanging out for a divorce and waiting for a summons when it had been achieved. The sharks that cruised past with scimitar fins were waiting too. For me. Every night black handprints, dipped in pitch, were left on the shutters of the shack.

Suddenly, and unexpectedly, a family arrived to set up tents nearby. It afforded great comfort. They looked like ordinary people, an American couple with a cluster of small children, minded by a ‘nanny'. She was neither family nor friend, and too mature to be a minion. Puzzling. Her hours ‘off' were late at night when we got talking, with wine if we struck lucky.

Suddenly, and unexpectedly, a family arrived to set up tents nearby. It afforded great comfort. They looked like ordinary people, an American couple with a cluster of small children, minded by a ‘nanny'. She was neither family nor friend, and too mature to be a minion. Puzzling. Her hours ‘off' were late at night when we got talking, with wine if we struck lucky.

Then she told me her story which made my own, comparatively, a walk in the park. It was a story so unlikely, so mythical and personally tragic that it lay untouched in the mind. My divorce came through. We kissed goodbye, and I never saw her again.

Ten years later I had remarried and had a child; a last ever child. In that post-delivery haze of delicate and transparent euphoria, floating above the ground, in the attic of a modest Victorian semi in Wiltshire, I remembered that blazing beach of light and terror in which a young woman told me of the loss of her baby. My own lay in a Moses basket at my side.

So I wrote it for her, a tribute to her tragedy, and it flowed mixed with milk and gall.It was the due paid, and yes, I wanted her mythical story as immortal as modest words could make it. I was blest, she bereft. Her suffering was mythical. I still hope one day she might find it.

So I wrote it for her, a tribute to her tragedy, and it flowed mixed with milk and gall.It was the due paid, and yes, I wanted her mythical story as immortal as modest words could make it. I was blest, she bereft. Her suffering was mythical. I still hope one day she might find it.

It almost wrote itself over a compulsive three weeks of sleepless nights, and I hardly changed a word. I am still far from sure I was really the ‘author.' If you read the book you can decide who might have been.

OVER TO YOU Do you have a similar story to tell about the inspiration behind one of your books? Please share it via the comments box below.

EASY TWEET “Fascinating story of the origin of a novel by @PhilippaRees1: https://selfpublishingadvice.org/why-I-wrote-this-book/ via @IndieAuthorALLi #writing”

[…] Why Do We Write What We Do? – The Compulsion of Story by Philippa Rees […]

That ‘story behind the story’ was beautiful. Sometimes these chances encounters bury seeds deep within us. I’m so glad you were able to nurture and grow something from the experience.

Thank you Rebecca. I suppose it was greatly sharpened by ‘living on the edge’. I often long for that sharp wind again. Somehow comfort and security dulls awareness, which I suppose is why on the road books and travel without destinations introduces it. But like the clearer vision caught in the corners of the eye, it can never be sought or manufactured. Any contrived ambition kills it!

Very moving and mysterious. Very Philippa I think. I also think that the story is bound together by the weird hormonal state of post-giving-birth, a very strange time which, so long as nothing much ‘goes wrong’ (making it medical and stark) can be quite magical. The world stands out in a different way as we live as new mothers (even if this is not a first child) in the rhythm dictated by the baby’s needs as it adjusts to being a separated being in the world not the womb, and the constant call of those needs which deny us sleep, rest, and being ourselves. Whatever the story of that woman, it’s kind of not surprising that it would return to another woman who;d heard it in the strained circumstances of awaiting divorce in such a strange setting, fraught with danger, far from western ‘civilization.’ It sounds intriguing and will sell the book!

Yes. Clare. You are very observant, both the circumstances in which the story was told, and the euphoria in which it was recollected were much heightened. The admixture of a precious new life into the memory of imminent threat made the whole connection very stark.

I suppose it is the one thing I have never been able to change for that reason!