Although British indie author John Lynch, who has lived and worked in every continent except for Antarctica, says he doesn't think of himself as a success story, he has achieved and continues to achieve an astonishing range and quantity of work, both under his own name and as a ghostwriter, and has been steadily writing away for many decades. He is a terrific example of:

- writing being a marathon, not a sprint (he's been “running” with his writing since the age of 12)

- writing effectively across many different genres – fiction and non-fiction of all kinds

- a positive example of a ghostwriter who actively loves writing under someone else's name (he also embraces it as a key route to productivity)

Read on for top advice and insights for indie authors everywhere from this inspiring role model.

Debbie Young sent me a series of nine questions and told me they were for a guest spot in Sunday Success Stories on the ALLi blog. That created something of a problem for me because:

- I don’t particularly regard myself as a success

- I found myself reacting to most of these questions the same way as I do when people ask, ‘Where do your ideas come from?’: “I really haven’t the faintest idea.”

However (and, as we all know, no real writer would ever begin a sentence with ‘However’), I’ll give it a go.

What's your proudest achievement to date as an indie author?

Just being here. I’ve been a writer, I suppose, since I was ten years old and stood on the stage of Benton Park Primary School in Newcastle to read to the assembled pupils and their parents a story I had written. I don’t, thank God, have a copy of it; the only thing I can remember is that it was about a garden and the garden was in Shropshire, which is where I now live, but at the time I hadn’t the faintest idea where Shropshire was. I just thought it sounded nice.

Then when I was thirteen I read She by H Rider Haggard (I wonder if anyone reads Haggard now) and Wuthering Heights, and I thought, “That’s what I want to do. I want to write books that make people feel how I felt when I was reading those.” But if you were brought up where I was you didn’t tell people you were going to be a writer because the nicest thing they might say would be, “Don’t be so bloody stupid.” Which is very good advice, as it happens, though not in the way they meant it.

At the time, the careers advice given to bright boys like me who lived in a council prefab but passed the 11+ and went to a grammar school was: ‘You can still end up down the pit or in the shipyard. Or on the bins, if it comes to that. But you’ve got a chance. Work hard, get a good job with a pension at the end of it and stay there until you’re 65.’

Apart from the “work hard,” which I have followed all my life, I ignored the rest.

I wanted to travel. An abiding memory of my childhood is sitting on the outside lav (we call them netties up there) of a relatives’ miner’s cottage in Durham with the door open and my pants around my ankles. At least, that’s what it looked like to anyone passing by – ignore all the remarks about “that disgusting little boy needs a slap around the head”; what I was really doing was driving a gypsy caravan down a road towards somewhere I’d never been. (Years later, I heard Lee Marvin singing Wandering Star. “Home is made for coming from, for dreams of going to/Which, with any luck, will never come true.” Oh, yes). I’d have done any job that paid for my airline tickets.

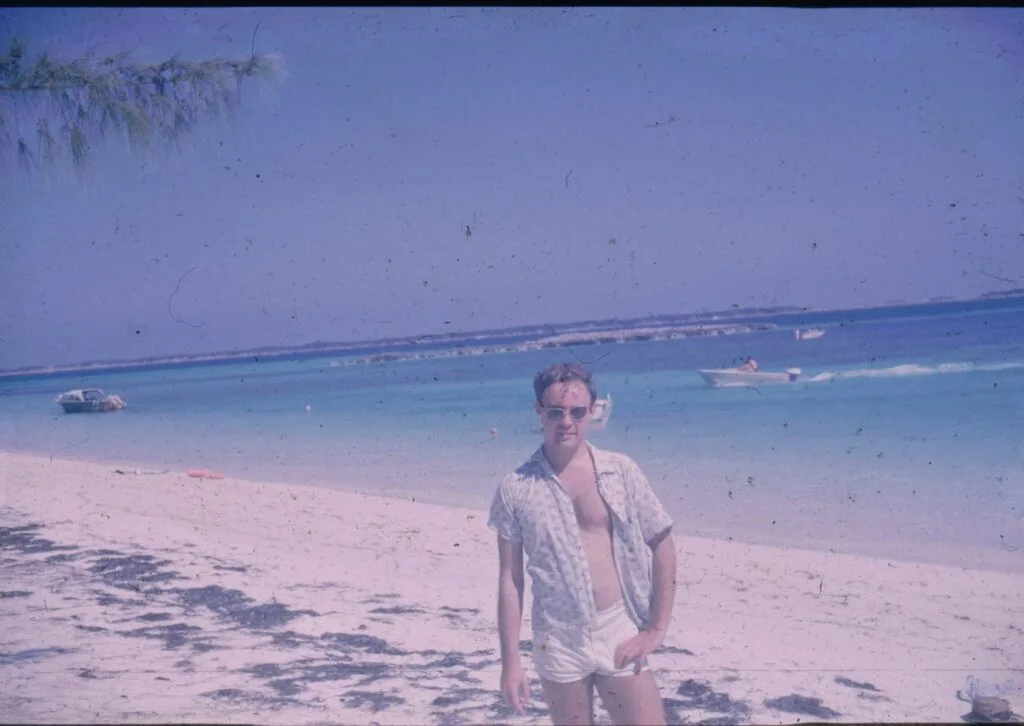

It turned out that international sales was the answer. In 1964, I was 21 years old and working in the Bahamas.

In 1966 – Africa. A big continent with lots to see.

And so it went on. I’m retired now, but I’ve lived and worked on every continent except Antarctica.

And, all the time, I wrote. And was rejected. And wrote more. And was rejected again. And then, scattered among the rejections, I started to get things like, “This is not for us. But, if you were to…” I followed all the advice any editor ever gave me. We were luckier in those days – the advice came more readily.

1989: breakthrough year:

- I sold my first article to a magazine (Good Housekeeping)

- my first book to a publisher

- my first story to the BBC

You can listen to that here if you want. When it was broadcast, I happened to be driving my mother from Shropshire to her home in the north-east and we listened to it on the radio. Her father, my grandfather, was the most intelligent person I ever met, but he went down a coal mine when he was 12 years old.

My mother also had a good brain (and still has, at the age of 102), but there was never any question of her taking up the scholarship she won when she was 12 – there were little ones to look after and the older children had to bring in money. And here she was, with a son who could get his story onto the BBC. It was nearly 30 years ago now and I don’t believe I’ll ever forget the expression on her face.

So, I think that must be the answer: selling that story to the BBC is my proudest achievement, and unlikely to be overtaken.

What's the single best decision you ever made?

Buying Dragon Dictate and sticking with it. It has transformed my productivity.

What's been your biggest surprise as an indie author?

Most of my work now is as a ghost writer, and I think what surprised me is the sheer number of us who are writing the books that are sold in large numbers with other people’s names on the cover. I was also surprised by how much I like it. Being known as the writer doesn’t matter to me, because I don’t have that kind of ego.

What I want to do is to write and be paid for it, because being paid for it means that it’s good, and ghost writing makes that possible.

I've set up flipbooks with portfolios of my ghostwriting:

What's your greatest challenge – and how do you deal with it?

If you look at my answer to the first question, you’ll see that my greatest challenge is a tendency to write too much. If you’ve met me, then you will know that I have a similar problem with talking too much. As far as the writing is concerned, I deal with this challenge by hard editing – I cut, then I cut some more, and then I cut again. (No, I haven’t done that with question one, because if I had I wouldn’t have been able to use this as an illustration). And for talking? I rely on people saying, ‘John. Shut up.’

How do you get/stay in a creative mood?

You’re kidding me! Underneath it all, I’m still the kid who sat in that netty with the door open and his pants around his ankles, imagining that he was driving a gypsy caravan down the road.

Making up stories isn’t my problem – my problem is re-entering what others think of as the real world.

How do you remain productive/motivated?

Ghostwriting is a very good way to remain productive. You agree an assignment, a word count, a fee, AND A DEADLINE. The deadline is non-negotiable. It’s amazing how that knowledge keeps writer’s block at bay.

I have to write it, so I write it. When I get to the end of a scene, I think, “Okay: what happens next?” Then I write it. Then I ask the same question. Repeat till finished.

What's your favourite thing about being an author–publisher?

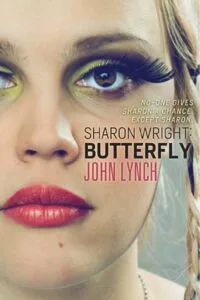

One of the contemporary novels published under John's own name. (He also self-publishes historical fiction as R J Lynch.)

When it comes to my own books, I like to be able to show them to people. I like the knowledge that they are well edited, that they are not full of little errors that should have been proofed out of there, and that they have good covers.

In short: what I like most about being an author-publisher is the ability to turn out books that look – and are – completely professional in every regard.

What are your top tips for other ALLis?

I wouldn’t presume to advise others. Except, perhaps, to say this. There are some truly fabulous authors in ALLi. People who turn out brilliant books that look, feel, and read as totally professional. Debbie Young herself. David Penny. Orna Ross. Anna Castle. Jane Davis. And lots of others, so if I haven’t mentioned you and you know I admire you, then please forgive the omission.

But too often I download an indie book and I find it’s sloppily produced or – and I’m sorry, but this is unforgivable – it is full of errors that should have been proofed and edited out of there.

So my advice is: I don’t care how many times you tell me you can’t afford it – you have to have a professional editor and you have to have a professional proof reader.

I’ve read a number of indie books that could and should have been top drawer but were let down by inadequate editing. You think you can proof read and edit your own books? I’m afraid we disagree with each other.

What’s next for you?

Oh, Lord. Who can answer that?

The problem with being a writer is that, when you get to the end of a book, you have learned how to write that book. What you have not learned is the more global lesson of how to write books. You have to start all over again.

Which is only one of the reasons why that advice I mentioned in question one in response to the statement, “I’m going to be a writer” (“Don’t be so bloody stupid”) is advice we should all have taken at the time.

Inspiration for indie #authors everywhere from @JLynchAuthor, a real #selfpub success story Share on X

GOod old John! I can say that because you’re younger than me! But then, everyone is! Anyway great advice! Back to work!