Paying for an editor is a big but extremely important part of the publishing process. Today, we hear from Alliance of Independent Authors partner member Amelia Winters on what you can learn from professional editors.

If you're an ALLi member and you're looking for editors, you can find dozens in our approved partner listings. Just log into the ALLi member website and navigate to APPROVED SERVICES.

So, you’ve finally done it. You’ve put in your last period, and you’ve finished writing your first draft. After the obligatory (and much deserved) celebrating, what do you do next? You know it’s time to iron things out and do some self-editing, but full manuscripts are these beautiful, huge, incredibly complex things. Where do you even start? I know our instinct as writers is to over-analyse the first thing we spot when it may not be the most pressing issue. Thankfully, there’s a better way. You don’t need to haphazardly flounder through your edits. You can take advantage of core professional editing principles to organise your edits. Doing so can help you increase both the efficiency and efficacy of your work.

I’m Amelia Winters, a writer and professional fiction editor. In this article, I’m going to use both of these perspectives to show you how you can improve your self-editing practice. I’ll also include some more focused advice for both emerging and established authors.

To start off, let’s take a look at what these core editing principles actually are.

Core Principles from Professional Editing

If I could only tell authors one thing about editing, it would be this. Editing the story will change the sentences, but editing the sentences won’t change the story. That’s why you should edit the story first and the sentences second.

That is, in a nutshell, why different types of editing exist. It’s also why the order of professional editing (and self-editing) is so important. Now, let’s get into the nitty-gritty. What is the difference between editing the story and editing the sentences? Stories are made of sentences, so wouldn’t all edits involve both the story and the sentences? This nutshell concept could do with some more nuance, and here’s where things get more complicated.

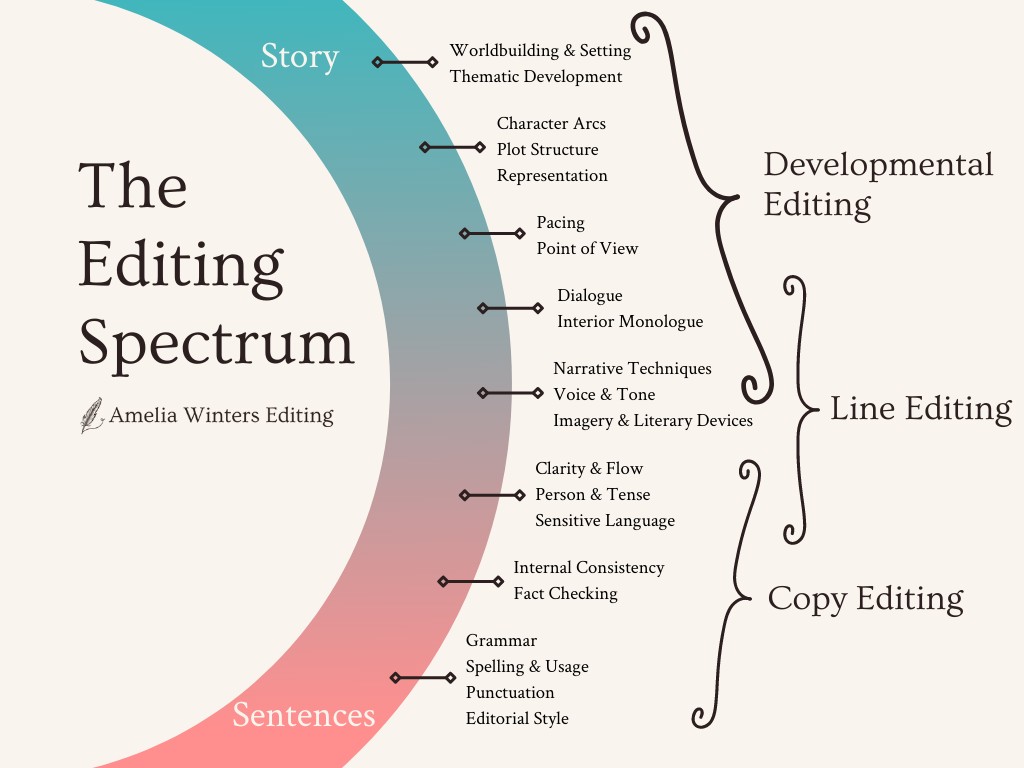

All edits exist on a spectrum, with broad story-level edits on one end and specific sentence-level edits on the other. In other words, editing tasks won’t always fit neatly into a binary category. Some editing tasks are more broad or specific than others. Others yet are hard to place strictly in the story-level or sentence-level categories. Remember that it’s best to approach all writing advice as a flexible tool rather than a restricting box. If you treat this spectrum as a flexible tool, then these categories can really help you organise the huge and nebulous task of editing.

So, let’s list some core elements of the writing craft and see where they would all fit on the editing spectrum.

How to Use the Editing Spectrum

As you can see in this infographic, there are many different elements of the writing craft. You can set aside time to work on each area individually. Note that you’ll need to make far more intensive changes to address issues related to topics at the top of this list.

For example, let’s say that you’re currently working on a high-fantasy novel. After getting some reader feedback, you’ve identified the following issues:

- Your writing has a lot of dangling modifiers and ambiguous pronouns. These issues are messing with the readability of the text.

- Your story is missing a compelling midpoint. This issue is making the middle section feel slow, dry, and uneventful.

- A specific element of your magic system is underdeveloped to the point that it is confusing readers and creating plot holes.

- Your characters’ manner of speaking is too stiff and wordy to sound realistic and fluid.

These are all important issues to address, but where do you begin? You can start by identifying where they fit in the story-to-sentences editing spectrum:

- Worldbuilding: Underdeveloped magic system

- Plot Structure: Missing midpoint

- Dialogue: Unrealistic-sounding speech

- Grammar: Dangling modifiers and ambiguous pronouns

A story’s worldbuilding will influence what events are and are not possible. As a result, it’d be important to sort out the magic system problem before you tweak with the plot. Then, to address the missing plot beat, you’d need to heavily change the story’s events. That will likely involve adding, removing, and rewriting multiple scenes. It’d be a waste of time to polish dialogue in scenes that need to be removed anyway to address structural issues. That’s why it’d be best to sort out the plot structure issue before addressing the dialogue issue.

Finally, improving the fluidity of your dialogue will likely involve heavy paragraph-level changes. You may need to restructure, reorder, or remove whole sentences. There’s no point tidying up a sentence’s grammar if you’ll need to change it anyway to address larger dialogue issues.

I hope these examples show you why the order of edits is so important. It is far, far more effective and efficient to edit the story first and the sentences second. You can use this infographic as a guide. It’s generally best to start editing issues at the top of this list and then work your way down.

How the Different Editing Levels Work

As you can also see above, editors group tasks together into different levels of editing. Developmental editors group story-level tasks together. They usually address issues from worldbuilding to literary devices. Line editors, also known as stylistic editors, work on the middle ground. They usually cover scene-level issues from dialogue to sensitive language. Finally, copy editors work at the sentence level. They’ll usually address issues from clarity and flow to editorial style.

Note that proofreading is another type of editing self-publishers should know about. A proofread is similar to a copy edit, but there are some important differences between the two. Copy editors and proofreaders edit the manuscript at different stages of the publishing process. The word copy refers to a manuscript’s unformatted text, and the word proof refers to a book’s formatted pages. So, the copy edit happens before the book is formatted, and the proofread happens after. Making changes to a book’s formatted text is costly. As a result, proofreaders need to edit much more lightly than copy editors. Proofreaders are also responsible for catching formatting issues and inconsistencies. So, in short, copy editors can edit more heavily for both eloquence and correctness. Proofreaders edit much more lightly for correctness and formatting issues.

Alright, let’s now look at what authors can learn from these professional editing levels.

How You Can Group Editing Tasks Together

Like editors, you can group related editing tasks together. Though I’ve identified separate editing areas, these areas are still closely interconnected. This is especially true at the story level. Your plot, characters, and themes are all interwoven with each other. What you do to one will affect the others. It’s still helpful to compartmentalise different editing tasks. Just be sure to keep other related issues in mind as you edit one area.

Let’s go back to that high-fantasy novel example. That example has two story-level issues: the underdeveloped magic system and the missing midpoint. As you’re editing the novel, you could ask yourself, are these two issues related? Is there a potential solution that could help you solve both problems? Could you introduce a magic-system mechanic that both resolves plot holes and adds conflict to the midpoint? With this wider perspective in place, you can sometimes find connected solutions to separate problems.

On a related note, when you’re editing, make sure you’re also aware of your story’s strengths, not just its weaknesses. First, knowing your strengths will help you accept constructive criticism without getting too disheartened or defensive. Second, you need to know what your strengths are so that you don’t accidentally squash them in your edits. You need that self-awareness to avoid throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

For instance, say some great character development happens during that fantasy novel’s slow midpoint. In that case, you should do your best to craft a gripping midpoint that still allows the excellent character development to happen. This is another reason why it’s important to edit one area of your novel with the other related areas in mind. That includes being aware of your specific strengths, not just your weaknesses.

Remember: Editing Approaches Are Flexible

Finally, you should also know that different editors will define their services in different ways. Some developmental editors may focus solely on the highest story-level concerns. They may not address scene-level areas such as dialogue and narrative techniques. Some copy editors edit very lightly for technical errors only. They may not restructure your sentences for clarity, coherence, and flow. Different editors have different approaches, and they’ll structure their services accordingly. That’s why it’s so important to get specific definitions for an editor’s services. That way, you can ensure that the editor’s approach is the right fit for your needs.

Likewise, you can be flexible with how you use the editing spectrum. You can define your own groupings of related tasks. You can tweak your order of operations to better fit your unique brain and unique story. Again, the framework I’m proposing here is meant to be a helpful guide, not a strict restricting box.

With these general principles in place, let’s now look at some editing tips specifically for emerging authors.

Editing Tips for Emerging Authors

As authors, our initial editing instinct is to fixate on the sentences without critically analysing the story itself. It can take discipline and self-awareness to pull back from that instinct. It can also be hard to analyse your story for much broader and deeper issues. Yet that analysis is a critical part of self-editing.

Here’s something I’ve noticed in my editing practice. New writers are especially prone to confusing sentence-level interventions with story-level interventions. Even when authors seek out developmental editing, it can be hard for them to grasp this distinction. You can’t fix structural problems by changing a sentence here and a paragraph there. Often, story-level editing requires making major changes to the story. You may need to add, remove, and completely rewrite multiple scenes. Yet that instinct to focus on the sentences—to polish each turn of phrase until it practically glows in its perfection—tends to be present throughout the whole process. Trust me, I know.

As hard as it can be, try to hold yourself back from fixating on your prose craft when you have structural issues to address. Also, make sure that you aren’t relying on sentence-level interventions to address story-level issues.

To be clear, I’m not saying that you can’t spend time crafting pretty prose during your writing process. Of course you should care about the quality of your prose as you write. If you happen to spot a typo at any point, you might as well fix it right away. Just don’t let yourself fixate on polishing your prose first. Wait until you are absolutely certain that the scene itself works and will make it to the final draft. This general guideline can really help you manage the limited resource of your time effectively.

Some Specific Tools

Here’s something I find helpful. If I don’t like how a sentence sounds but I’m not ready to polish it yet, I’ll simply highlight the sentence or put it in brackets. That way, I can easily spot the clunky construction later. In the meantime, I can continue writing or doing other structural work without worrying about it.

There’s another benefit to focusing on the story first and the sentences second: it makes necessary cuts easier to make. It is so much harder to delete a superfluous scene when it contains gorgeous prose that took you ages to write. Yet to craft a strong story, you’ll sometimes need to kill your darlings. You can help yourself avoid this situation by waiting to polish the prose until after you’re certain the scene is a keeper. Still, that’s not always enough to avoid this situation. You’re going to write some beautiful passages in your first draft that are difficult to cut.

Here’s something I do that helps me kill my darlings. (To give credit where credit’s due, I first heard this advice from Patrick Rothfuss at NerdCon: Stories.) When I’m writing, I create a separate document called “Sentence Scraps.” I can banish my superfluous sentences to that document without actually deleting them. I can then save those passages for potential future use in a different scene. I almost never end up using my sentence scraps again, but that’s not actually the point. Simply letting my abandoned sentences continue to exist somewhere makes it easier to remove them from the current draft.

Editing Tips for Established Authors

As writers, we are also lifelong learners. Established authors often have an incredible learning resource: reviews from your readers. The feedback in these reviews can help you find out which issues are most important to your reader base. You can use that knowledge to focus your professional development in those areas.

Though do be careful to focus on critiques that come from your true target audience. Different readers like different things, and you’ll never write a book that’s everyone’s cup of tea. Readers outside your target audience may pick up your book and not enjoy it because it wasn’t written for them. Say an action-adventure, high-fantasy reader picks up your literary, low-fantasy novel. They may critique your novel for having too much dialogue and not enough action. Say a thriller and suspense reader picks up your cosy mystery. They may critique it for being too campy and not gritty enough. Finally, say a YA romance reader picks up your adult historical romance filled with political intrigue. They may critique it for being slow and dull.

These critiques are not rooted in true problems with the story. They’re rooted in a mismatch of genre preferences. Most readers won’t be able to tell the between their genre preferences and more objective narrative issues. So, you’ll need to filter your reader feedback for yourself.

(By the way, if you do find that most of your readers are not your target audience, then that’s usually a sign that you have a marketing problem on your hands. Know that your marketing materials may be misleading readers about the kind of story your book is. However, the ins and outs of effective marketing are a larger discussion for another time.)

What to Do with Reader Critiques

Once you’ve compiled the relevant critiques that resonate with you, you may find several areas to work on. In that case, you can use the editing spectrum to group your learning into different chunks. This grouping can help you avoid feeling overwhelmed by making it easier to focus on one area at a time.

As you start planning your next novel, you’ll especially want to keep story-level critiques in mind. That way, you can avoid those past pitfalls this time around.

Also, you may get scene-level critiques, such as issues with your narrative techniques. In that case, you may want to do some experiments in a sandbox document before you start working on your next draft. These low‑stakes experiments can help you strengthen your scene-level skills. They can also help you find new creative techniques to better immerse readers in the writing.

The same goes for sentence-level issues. Say that repetitive grammar mistakes are messing with your text’s readability. You can practice crafting the kind of sentences you find tricky before you start your next novel. With this practice in place, your first draft will likely be cleaner and need fewer edits down the road.

Before you start writing, you may even want to take a bigger step back. You can take time to read craft books or do workshops on the specific areas you struggle with. Again, doing this work before you start writing can help you write a tighter first draft. Writing a cleaner first draft will reduce the amount of editing you’ll need to do later.

This discussion on target audiences brings me to my final point, which is relevant to all authors.

Know Your Audience

I’ll leave you with this last piece of advice: know your audience. As personal as our writing is to us, we are not writing for ourselves. We are writing for our readers. To make sure your writing is connecting with your target audience, you need to know who your readers are and what they value most in their stories.

In an ideal world, all authors would be masters of all the elements of the writing craft. Practically speaking, though, we’re all going to have strengths and weaknesses. We’re human. It’s often enough to have a solid grasp on most writing areas and be a true master of only a handful of them. We don’t need to be perfect to write a story worth reading.

Also, our time is limited, and the writing craft is huge and incredibly complex. So, what parts of the craft should you prioritise in your personal development? Again, it comes back to your audience. What parts of the story are most important to your readers? If you can hit those parts out of the park, your readers will be much more forgiving of mediocre writing in other areas they care less about.

Then Let Your Readers Guide Your Learning

Here are some examples of what different readers tend to value most.

- Literary Fiction Readers:

- Strong character development

- Beautiful prose

- Deep imagery

- Classic High-Fantasy Readers:

- Immersive and compelling worldbuilding

- Well-developed politics

- High-stakes conflicts that impact not just the protagonists but their entire world

- YA Low-Fantasy Readers:

- High-concept magic systems with lots of intriguing implications

- High plot-driven stakes

- Rapid pacing

- Riveting romantic subplots

- Historical Fiction Readers:

- Immersive descriptions of the setting

- A tight plot that explores the unique challenges of the period

- Compelling characterisation that humanises history

- Contemporary Romance Readers:

- Complex characters

- Compelling character arcs

- Well-placed steamy scenes that pack a lot of emotional payoff

- Crime and Thriller Readers:

- Rapid pacing

- A continually compelling mystery with a satisfying resolution

- Tight prose

- A strong and unique narrator voice

I could go on and on. There are so many different genres and different readers out there. Even between subgenres, there is so much variation in what readers want. Know who your readers are and what they value most in their stories. You can then focus your energy on really mastering those areas.

It’s still good to aim for excellence in all areas, but you also don’t need to flounder under the weight of such a huge endeavour. If perfection were the bar to publishing, most books wouldn’t get published. Again, you don’t need to be perfect to write a story worth reading. With our limited time, it’s often best to focus on mastering the areas that our readers value most.

Amelia Winters, professional fiction editor.

What You Can Learn from Professional Editors: Summing Up

We’ve covered a lot of ground in this article because there's a lot you can learn from professional editors. The key concept to remember is this: editing the story will change the sentences, but editing the sentences won’t change the story. That’s why it’s important to edit the story first and the sentences second. Hopefully, you now have a more nuanced understanding of how editing the story is different than editing the sentences. You can always come back to the above list of editing tasks and use it as a reference. With the editing spectrum in mind, you’ll be able to better manage your time and organise your self-edits. I wish you all the best in your own editing and publishing journey!

Amelia Winters is a professional fiction editor, language nerd, and story aficionado. You can learn more about her editing services at wintersediting.com. You can also get in touch with her directly at [email protected].

Amazing!

I want to express my gratitude to you for the amazing content that you have shared with us. I have a strong conviction that adores and learn more about this subject. I have consumed a significant portion of my free time by reading the stuff that you have provided. Many, many thanks for your assistance.