On the AskALLi Beginners' Self-Publishing Salon, Orna Ross and Tim Lewis look at editing. Money spent on editing is not just a necessary investment in your book but also in your writing and publishing future. Every writer needs an editor, but getting the most from your investment can be challenging, especially when you’re starting out.

On the AskALLi Beginners' Self-Publishing Salon, Orna Ross and Tim Lewis look at editing. Money spent on editing is not just a necessary investment in your book but also in your writing and publishing future. Every writer needs an editor, but getting the most from your investment can be challenging, especially when you’re starting out.

Orna and Tim explain how to decide which type of edit you need, how to choose the best editors for your books and how to work with them to get the best creative and business return on your investment.

Also, on Inspirational Indie Authors

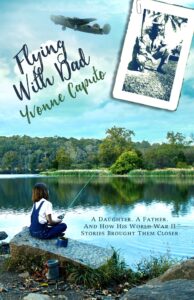

Howard Lovy interviews Yvonne Caputo, author of Flying with Dad: A Daughter, A Father, and how his World War II Stories Brought them Closer.

Howard Lovy interviews Yvonne Caputo, author of Flying with Dad: A Daughter, A Father, and how his World War II Stories Brought them Closer.

Growing up, Yvonne did not have a very close relationship with her father. A member of the WWII “Greatest Generation,” her dad was very brusque with her and did not show very much emotion or affection. That was what was expected of fathers of his generation. They were also expected to simply put the war behind them and move on with their lives.

It was not until Yvonne was sixty years old, and her father near the end of his life that he finally opened up about his experiences, both humorous and sad, during WWII and about the nightmares he had ever since. At last, after nearly a lifetime, Yvonne found a sense of closure with her father. It took her about twelve years to finish this book, which is about her dad, and her, the war, and so much more.

If you haven’t already, we invite you to join our organization and become a self-publishing ally. You can do that at http://allianceindependentauthors.org.

Now, go write and publish!

Listen to the AskALLi Beginners' Self-Publishing Salon

Subscribe to our Ask ALLi podcast on iTunes, Stitcher, Player.FM, Overcast, Pocket Casts, or via our RSS feed:

Watch the AskALLi Beginners' Self-Publishing Salon

About the Hosts

Orna Ross launched the Alliance of Independent Authors at the London Book Fair in 2012. Her work for ALLi has seen her named as one of The Bookseller’s “100 top people in publishing”. She also publishes poetry, fiction and nonfiction, and is greatly excited by the democratising, empowering potential of author-publishing. For more information about Orna, visit her website: http://www.ornaross.com

Tim Lewis is the author of three time-travel novellas in the Timeshock series and three fantasy novels in the Magpies and Magic series under his full name of Timothy Michael Lewis. He is the host of the Begin Self-Publishing Podcast and is currently working on the book Social Media Networking- a guide to using social media to find your dream job, find love and boost your travel experience.

Read the Transcript

Orna: I'm here with Tim Lewis. Hi, Tim.

Tim: Hi Orna.

Orna: Welcome to another Alliance of Independent Authors Beginners Salon. And you're just back from your holidays, right?

Tim: Not holidays, clearly all business. So I went to a conference in San Diego but I also went to Boise, Idaho beforehand and also Santa Fe and I've got a t shirt, a very cheap tee shirt I've been wearing since. So yes, I suppose it was a holiday in a way. So yes, I was away.

Orna: I'm onto you, mister. I know it's not business. Well, it's half, it's half, it's hard for us to separate business and pleasure when you love what you do.

Tim: Yeah.

Orna: So today we've got quite a bit to talk about because we're talking about the really important topic of editing and it's a big topic for authors and especially when you're starting out, I think. This is our Beginner Salon where we speak to people who are at the earlier stages though I know that we have listeners who are listening at all stages of the process and some people who've been doing this for quite a while. For us all, editing is absolutely key. So do you want to just say quickly why that is? Because I know that there are still some independent authors who need to be convinced of this because of course, editing is expensive. It's one of the most expensive investments that we have to make. And there is some resistance to that. Can you talk first of all about why it's so important?

Tim: Well I think the basic reason why editing is important in any activity, I mean I came from an IT world, I used to be software development and there was always big pushback there for having software go through quality assurance testing. And going through, like, having a second pair of eyes looking at it. And it was for kind of similar reasons in as much as it's extra time and expense and having that second look of it. But when you work with a good editor in the same way, when you work with good software tester, it's all about the fact that you're making use of both a second perspective, which is important in itself because you are so invested in your own words that you may be totally blind to all sorts of major faults and also the fact that you are making use of their experience in testing or in editing a book, especially this is especially true of genre work where you've got an editor who really knows that genre.

Tim: So for example, with some of my books, my mum was an editor, like in a general, like, way in the 1960s. But because I've switched genres I think I may have got better service from somebody who really understood the genre because as we talked about in previous episodes, there are things that are different and expected in certain genres and certain things. And if they're missing, then that can put somebody off. And somebody who is an editor who has experienced in a particular genre or a particular type of writing can really, really help you spot the things that are wrong in your, well, not wrong, but can be improved in your manuscript. So I think an editor, I mean if you're only doing a 20 page book then maybe an editor's not essential, but if you're doing any kind of serious work, then you really do need to have an editor of some variety. And the better, the more skilled and more specific to your genre, the better.

Orna: Yes. And of course at ALLi we define a book as something coming in around 50,000 words or similar. So yeah, at that level editing is essential and especially at the beginning. And the, the difficult thing I think is at the very time where you have least money, you know, you're not getting any income. It's your first book. You haven't, it's all still all so new to you. And you've got so many other things going on. The idea of committing to this amount of money and this amount of time and the handing over, the taking the critique, all of these things, are much more challenging first time out. And so the very time when you most need it is the very time when it's most challenging, but we really urge everybody to get the best editing you can afford.

Speaker 3: And see it over and over and over again. That when people find the right editor, that's when their career takes off because an editor will, it's a learning experience. So it's not just an investment in that one book. It's an investment in you as a writer and you will learn so much from your first data's more than almost you've learned just from writing the book yourself. It's, it's a hugely rewarding and interesting and a growing experience if you will open yourself up to it. So it really is a huge investment in you as a writer so think of it in those terms that you will be getting a repayment on this investment all the way through all the books that are going to be coming down the track. And also we always say that, your editor is actually your best, is your first marketer and your best marketer because if you don't get you a book edited, it won't be as good as it could be. That goes for everybody. You know, the people who have been writing forever. Stephen King, his next book, will have an editor and, you know, everybody, no matter how experienced needs that and yes. So, okay, not to labor the point anymore. And if there are, however three different types of editing and again, at the beginning you're likely to need them all and you're likely to need more editing and you need later on when you're more experienced and you know, all the tropes of genre and so on. So the three kinds of editing are developmental editing, line editing, sometimes called copy editing. And then proofreading at the end. So I think what most writers will now recognize the need for proofreading the resistance often comes in for that developmental edit. So your genre person that you're talking about where they a developmental editor?

Tim: Well, no, it's the same. I basically use the same editor all the time. It was just general editor. So, but I think that you're right, as in, I can see that a developmental editor would be phenomenal, for certainly for starting writer and for somebody in it who knows. I mean, I think there's a lot, I mean I've heard a lot of stories and maybe some of this is you, you in your ALLi role would know about the, how important and the personality fit is between the editor and the actual writer, so it's not just a case of an editor being really good if they don't have the kind of personality and relationship with the writer. So I mean, yeah, I think probably, well, should we start with just explaining the difference between those three types of editing? So-

Orna: I think, I think that's, that's really necessary. Yeah. So I'll take developmental edit then first, but just to pick up on your point before leaving it, because I think you raised a really interesting point there around personality. Again, another thing that we kind of say is that finding an editor, you know, finding the editor, it's like finding a spouse, you know, it's that important and it's that personal and there's, you know, there's sort of personal chemistry issues there as well as things like, just how they give the feedback, the kind of language they use, whether that fits you, fits yours, you know, whether they are, if you are a highly creative, you know, that they can account for that and allow for that while pinning down the things they need to pin down and so on. And yeah, so those, you may, this is a trial and error thing and it may take, in fact, it almost always does, I think, if you get the right editor first time out that's pretty lucky. But regardless, no matter, even if you don't get on that well at the beginning. Even if they're not the perfect person, you'll still learn a huge amount.

Orna: So don't say, “Okay, this isn't the perfect editor for me. I don't need, you know, I'm going to wait this time and see if I can get the right person next time.” It's still a really valuable learning experience. Even with that in place. So developmental and particularly again, with each of these, we have to talk slightly differently in the three big genre divisions of fiction, nonfiction and poetry. So very often people advice around development, editing focuses on fiction writing. So there you're talking about issues around the story, consistency across the storyline, these are what you call, the big issues, the structural issues.

Orna: Sometimes it's called structural editing. It can be called content editing sometimes or substantive editing. One of the things you realize when you go looking for an editor is how confusing all these different terms are and there isn't an agreed sort of a definition but there really are only the three types. And so I'm going to stick with the word developmental editor because I think that's the most useful in that they do develop the book. So it's like a screen, like a screen, you know, a script in screenwriting goals into development. We don't have that same concept quite as also is in publishing because a lot of that goes on behind, more goes on behind the scenes than it does in screenwriting.

Orna: So what they will do is it will flag any big inconsistencies. If you've got a big hole in the middle of it and didn't even realize you had. If your logic in a nonfiction book is not holding through, start to finish, if there's a chapter that should be there that isn't there, if you've, you know, quoted two different people and haven't noticed, you know, all of those kind of big picture, I suppose, issues is what you would talk about. In poetry it's a little bit more subtle and it's more like a teaching role with poetry because that's a short piece and lots of poets don't hire editors on the basis of the work is short. But again, I think there's a huge amount of value in having a poetry editor, especially at the beginning.

Orna: They can teach you so much about form and language and how those two things come together and you know, lots of stuff that you may have learned in English class and didn't really understand at all when you were considering other author's book begin to make sense for you when you actually look at it in terms of your own writing. So anything to add on the developmental or do you want to talk about the line editing/copy editing thing?

Tim: Well does that mean you want to talk about it? But no, I mean the funny thing is there are gradual kind of, it's not night three nice buckets that you can put all these editing things in. There are lines between them. I mean developmental editing also kind of overlaps with writing coaches. And I mean, you could say that even ghostwriting is extreme developmental editing, i.e. the other person actually writes it for you, more the line editing is more to do with how your sentences and structures and how everything works in terms. So it's not the spelling and it's not like the individual things, but how does it sound? How does that, like, how does the text flow? Not so bothered about plot points or the actual story, but it's to do with like making your book sound and read as good as possible.

Tim: So things like repeating words would be something I would guess that will be more in the line editing side or again, you could, maybe that's in the proofreading side because the trouble is proofreading is different for print than for ebooks because of the nature of the two things. So it's kind of like this is, there's a spectrum of editing that's available from like where somebody really holding your hand and telling you about, like, everything, to kind of trying to make your structure, your actual writing skills better by showing you what needs to be changed and then all the way to proofreading, which is more of a how your actual spelling mistakes and how your book is actually structured in terms of a paper book. So it comes from the old concept of proofs where imprinting you used to have a proof where you went through when you created the print that you actually were going to put on these little tablets on the printing machines. So proofreading is checking the proofs had no spelling mistakes and that you didn't have like an extra word on one page and that kind of an orphan or that kind of thing, with ebooks because of the flowability of it, that element of proofreading's probably less relevant, but you still got spelling mistakes and grammatical issues and the rest of it. So that's kind of the other extreme of the spectrum of editing that we're talking about.

Orna: Exactly. And I think that the ones that people do tend to mix up and not know for sure whether they, which one they need is that gray area between the copy editing, or the line editing as it's sometimes called the proofreading. So a lot of authors would say to me, “Well, you know, if somebody is going to fix up the spelling and everything, you know, why do I need this, what's this line editing doing if it's not doing that and it's the hardest one to explain and it's the one that will probably have the most effect in terms of reader enjoyment, well, that's not fair to say, they all do, but it's just the, it's about the language and you use the word flow and I think that's exactly it. It's very hard work and writing long form.

Orna: You know, once you go over 10,000 words, the sentence fatigue sets in, you don't recognize sometimes when you've kind of dropped the ball on your sentence, maybe it doesn't even make sense at all but probably does satisfy grammatically is fine. But it could be said in a better way. Or you've used far too many say passive constructions or you got repetition that you don't realize you have and that can be repetition not just of of words though that definitely does happen where people use the same words over and over again or the same little phrases but also repetition of effect. So when you, perhaps you have a scene structure, you know, four or five or six times within the book and you don't even realize you've done that, essentially somebody else picks up on those kinds of things. So that will be at the structural level. The same thinking man can happen at the language level where you're using phrases, dialogue forms, you'll see a lot of with beginner writers where the dialogue takes a similar sort of pattern over and again, and while you do want your characters to speak in identifiable voices.

Orna: You don't want the dialogue to become repetitious in any way. So it's, again, it's a subtle thing and yeah, as you say, Tim, where it breaks down, nobody can draw a line and say categorically that's on the line editing side, that's on the proofreading side for everything. It's important that to have two different people do your line edit and your proofreading if you can. It really does make a difference if, because by the time your line editor has done the line edit, they, like you, are now too close to the text and don't have quite what it takes to do a very accurate proofread. This isn't as important as it used to be with machine editing. So lots of editors now will use some kind of software to help them in proofreading and in line editing. So it's not quite as important as it use to be at that. But still I think it's helpful and also with every editor you work with, you learn a little bit more. So, yeah, any other tips for working with the editor?

Tim: No. No, of course, it's a personal thing, working with an editor. You have to kind of, you have to be prepared to emotionally detach a bit from your work so that you don't take it personally. Because also I realize on the other extreme that you'd don't have to necessarily take any notice of what the editor says. You are the person who is paying them and it's a contractual relationship, but you need to be questioning yourself if you're saying, or if you just keep overriding what the editor says all the time, then that's an issue.

Orna: Yeah. If you find yourself. Oh, sorry, go ahead.

Tim: Yeah, no, I was going to take things off on a tangent to describe why, like, why editing is important in general. Something came to my mind. If somebody was editing this podcast from a developmental point of view, they are probably saying that I should have said this earlier on.

Tim: So that's a example. But there's a video on youtube where they go through the edits they made the first Star Wars film from an editing point of view and it's phenomenal the changes they made in post production because anybody who knows the history of Star Wars knows that he had this big presentation to people like Steven Spielberg and Brian Depalma. And they all thought it was rubbish. They thought it was a terrible film that would never succeed, but that's because they sold the pre edited version of Star Wars. So, just as an example about how they changed it in the edit, right at the end, do you know there's the big scene where Luke Skywalker's going down the trench run in the Death Star. In the original version, the rebel base wasn't under threat at all. They just had it as them going flying off to blow up the Death Star.

Tim: If you watched the first star wars film, every single scene at the end of it where they've got like the little clock and the timer saying like, oh, it's going to be in range soon. That is all added from stock footage. None of that has any of the characters because they added it all in the edit. So-

Orna: It's fascinating.

Tim: That's kind of an example of how good editing can make something that was kind of like meh into, like, really good, from a developmental point of view. Because it was developmental editing. They basically chopped the whole thing up. So the original Star Wars was very different from the one that we actually ended up seeing. So that was my tangent.

Orna: That's good. It's good. And I will definitely be going off to take a look because I'm always fascinated by what an editor brings. And I also feel that the editors should be given a lot more credit in our books, you know, and generally for the work and I know some authors who really feel that their career is down to their editor. And I know some editors in traditional publishing who have handled a stellar cast of writers and you can see when you know that they are the editor you can actually see their work in play across very different styles. So it's a huge creative skill in itself and it deserves more, you know, more credit is due and editors tend to be very, you know, a bit self effacing and interested in the work rather than being out there being the star or whatever.

Orna: But they definitely deserve a huge amount of credit, more credits than I feel the traditional publishing industry has afforded them where they're being very much, you know, kept in the background. And I think it's interesting, one of the things that's happening with the indie author movement is that authors are actually acknowledging their editors much more and talking about them and bringing them out out to the front. So just a few tips then on actually working with your editor. And Tim mentioned, you mentioned earlier you should be seeking an editor who's comfortable in your genre. That's really important. Somebody who specialized in a particular genre or particular type of, if it's nonfiction in your subject matter, they're going to bring their expertise and that's absolutely fantastic. And different editors have particular strengths and it's good to think about. Can you find somebody who's kind of strong where you're weak?

Orna: So if you know, for example, that you're not great at dialogue or structure, getting an editor who's very good at that or if you're not great on description, somebody who's good on those kinds of things, seek them out. Another thing to think about is nationality and region. Are you going to write the two major forms of English, US or UK? Which one are you going to do? Does your editor have expertise in that and you should have some kind of style guide that is a basis of what you will work on. If you don't know what I mean by style, essentially it's just decisions around conventions. Like, when do numbers get written out as words for example, or do you use the Oxford Comma or not? That kind of stuff. If you don't have one already, that's absolutely fine.

Orna: As a beginning self-publisher you're not likely to have one. But as you work with editors, begin to agree, you know, come to a sense all of your own house style, of what your preferences are and make those, you know, set up a style guide for yourself so that the next editor you work with, you can actually and tell them what your preferences are around that. In terms of hiring somebody, it's good to actually test with a sample edit. So, and you can ask them to send, you know, you send them a sample of your work and then ask them to take a look at it. And you know, very often they will quote you a price based on that work. Editors are sometimes reluctant to quote prices up front because it does really vary hugely depending on the writer skills.

Orna: But at ALLi we ask that all our partner members at least give a range of where they begin and end because this is something that can vary so hugely among editors that I think authors need to have some sense of what it might cost them, but it is going to vary hugely depending on your own writing and the editor's expertise and how long they've been in business and you know, how much they value themselves essentially as well. What else? I think those are the major things to think about. Yeah, anything to add to that, Tim?

Tim: Well something I recommend people doing, which I kind of did myself a little bit, but two things that for your first book project, unless you think you're only ever going to write one book, which is quite negative attitude, you probably want to be looking for something that's fairly short relative to what your other work you want to create and also isn't your big passion project so that you can, like, afford to give it the attention it deserves in terms of editing because editing a shorter work, it's going to be cheaper than editing a longer work in general. And also because you probably, if it's like this thing that you've been willing to, your passion project that you'd been wanting to get out of it, then that's possibly not the first best first project to work on with an editor.

Tim: You probably want to be able to, and you will also, even if you hire an editor, you don't really get on with least you'll learn what you need to work on because they will almost certainly tell you. So I think there's, like, there's something in terms of your career, in terms of writing. Maybe the first one should be a short thing that you're fairly confident about in whatever genre you're interested in, learn all the ropes, learn how the editing process works, learn your what kind of editing you need and who you need to focus on. And then maybe in the next book, if you're lucky, you'll get the great editors you want in the first book and it will be cheap enough. But if you don't, then it's like, it's a short work. You're not spending that much on it. And then for the later projects you can start really, cause the more books you write, the better you're going to get both in self editing and in choosing people and in the whole marketing process and everything. So that's why I was kind of say to people, “Write something short to start with if you can, and then, like, go onwards,” with like, and that applies to because of the editing costs and everything else. So that would be my advice.

Orna: It's really great advice. And if you can take it. I wish I had, I started my writing career with a ridiculously long and ambitious project, which eventually broke down into three books. Crazy stuff. But something else you said earlier is also relevant here in that, you mentioned the relationship that you have with the editor that you're paying them. So this is slightly different to the way in which traditional publishing has worked, where you hand over the manuscript, basically, they choose the editor for you and it's sink or swim. You either get on with them or you don't. And you know, they, and as we've already said, you will learn anyway.

Orna: So don't worry too much about that. But what can happen sometimes, and again it won't with an experienced editor but sometimes beginner authors end up with beginner editors because of cost factors and what can happen in that case, and in terms of the relationship is that because you're hiring in a sense you don't get, the editor should lead in, in this stage of the process. And that's quite difficult for the author sometimes. It gets much easier as you get more experienced. But at the beginning when it's this precious baby, and this is another reason to kind of do what you were saying, Tim, to do a lighter, you know, project that isn't like your absolute baby as your first time out and, but if it is something to check in with is your level of emotion to the responses. So if you're finding yourself irritated, upset, you know, if the motion is running high in you as you are responding to the edit, that may not be a personality issue. That just might be that you need to take the attitude that is appropriate for an author and need some practice at that because a lot of us do starting off, we're very sensitive about the work.

Orna: It's very exposing to give it to somebody else and to get it back if it reminds us of school as well and possibly previous humiliation to the hands. Hartl teachers. And you know, there are all sorts of things going on here and the learning experiences as much in that whole thing of learning how to accept that as it is in actually improving the writing. So there are tips online and if you check out the Self Publishing Advice Center, we have a number of articles about editing, which you can look at there. And in terms of Carl Drinkwater has written a good post about how to, you know, how to take the criticism, if you like, the right attitude to bring to reading your edit and you know, don't make sure you give plenty of time and space to it, that you sit down with a cup of coffee, you know, read it through, observe your own responses and reactions and allow some time to cool off if you need that before you begin to think about what you do and don't do, you should be taking the notes from your editor and analyzing them.

Orna: As Tim said earlier, you're the person who will make the ultimate decision. But if you find, as he said, that you're rejecting loads of them or if you find that you are highly emotional about it, then the right attitude, the right place to be in is to have a cool head while you are actually taking the notes on board so you can make good decisions.

Tim: Yeah.

Orna: So just briefly before we leave, we're almost out of time. Editing UK has popped in to say hello, an ALLI partner member and that answers a question from somebody else here. Walt has asked “Any hints on how to find a developmental editor?” So we have a directory of all our partner members, Walt and across the seven stage self publishing process, which Tim and I are going to be covering in coming months and so if you check out the directory, everybody there has been vetted by the ALLi watchdog desk and you can begin your investigations there. So anything to say before we bow out?

Tim: No. Apart from to point out to anybody who is expecting a Twitter chat, there's not going to be a Twitter chat today, but I suspect at some point we may be having more regular Twitter chats.

Orna: Yes, we are going to. We've both been away. I have been on my absolute holidays with no business involved and Tim was away, so we didn't do the session on Tuesday as usual though it will go out at the usual time on the Saturday podcast. But yes, we feel that a Twitter chat after and the ALLi chats, after the ALLi sessions would be useful for people to go and kind of talk about the issues afterwards. So we're going to try and set up a weekly, and we will be, we'll let you know when the member magazine about it exactly what we decide around that, but it will be on Tuesday evenings and we'll be back with the Facebook live session on Tuesday on the first, is it the first Tuesday? Yeah, the first Tuesday-

Tim: First Tuesday, yeah.

Orna: First Tuesday next month with the Beginners Salon again. And next month we'll be in the next stage of the publishing process, which is all about design and what you need to think about there. And that one will be followed by a Twitter chat then. But if you do have any questions, please put them in the comments here and we will address them afterwards. And of course you can contact us anytime on all the usual addresses and places. So hopefully that was useful to you as you consider the editorial process. And thank you for being here with us this evening.

Tim: Thanks a lot everybody.

Orna: Bye. Happy writing. Happy publishing.

Howard: I'm Howard Lovy and you are listening to Inspirational Indie Authors. There are many reasons to publish a book and all of them are personal to the author, often it is to honor a family member or to come to terms with something in the author's past. This is often the subject of first books. They're often so personal that it's difficult for readers to find a connection. It's a tricky balancing act between what is interesting to you or your family and what everybody else might want to read. Yvonne Caputo took about 12 years to find that balance that she came up with her soon to be released book Flying With Dad, a Daughter, a Father, and How His World War Two Stories Brought Them Closer. Hello Yvonne and welcome to Inspirational Indie Authors.

Yvonne: Thank you. Good to be here.

Howard: So first of all, did I get that basic dilemma right? This need for something personal and universal at the same time in your book

Yvonne: You did my father would have been considered the greatest generation. And what he felt being a father was all about, was providing a roof over our head and making sure that there was food on the table. But having a closer relationship to his children was not something that was in his, let's say, worldview.

Howard: That's what fathers of his generation were expected to be. A little more brisk.

Yvonne: Yes, absolutely. And so as a child, there were so many instances for me that I wanted more. I wanted to have that close knit relationship with him. I had it with my mother, but I also wanted it with him. So the book came out of that relationship in the oddest of ways. In 2008, he and I were doing our weekly phone call. My mother had passed away, so when he picked up the phone, he could no longer say, I'll get your mother. And so in that one phone call, he just opened up about this quirky, funny, off the wall, World War II story. And I said to him at the time, I said, ” Wait, I want to get a pencil and paper. I want to take this down.” And his deep resonating voice came back with, “Well, what the hell do you want to do that for?” I said, “Dad, I think this is a story that I should put on paper so the rest of the family can hear it.”

Howard: How old were you when you heard the story for the first time?

Yvonne: I was in my sixties. He had never talked about the war. I mean, we as children knew he was in it. We knew that he'd been a navigator. We knew he flew B24s. We knew when he flew out of England, but those little detailed stories are just something that he'd never talked about. So he was a storyteller and he loved engaging people, particularly in funny stories. So I think that's how it just spilled out. But the next week when I called him, I said, “If you're willing, Dad, start at the beginning.” He said, “Well, what do you mean?” I said, “Well, how did you get into the war in the first place?” And he just then opened up and week after week we would go from what his life was like and how he got training to repair airplanes and how that led to flying in an airplane to his deciding to petition to get out of his presidential deferment and go into the war. When he repaired this plane, the pilot insisted that dad get in it as well. And when he was up in the air, he said, “Yvonne, I remember,” he said, “I didn't want to fix them anymore. I wanted to fly them.” So his reason for going into war was not what many people thought. He wanted to learn to fly.

Howard: A lot of World War II stories have been told and there's some similarity between them. But also each one is unique in their own way. Each individual had their own private war. What is unique about your father's stories?

Yvonne: They were more personal in nature. They were the things that he remembered. They were how insecure he felt when he was in navigation school because he was so afraid he wasn't going to pass. They were stories about other GIs that he was with and what it was like when they didn't get their wings, you know, there were stories about riding his bicycle around England. There were, it was just these intimate details that gave me this picture of my father that I'd never had before. And the more we talked, the more he opened up and the more he opened up, the closer we got. For example, he came back from the war with horrendous nightmares and he told me what those nightmares were. And at the end of his story, I said to Dad, I said, “I'm really so sad that they didn't know at the end of the Second World War what we know now. And it would have been a whole lot easier for you if you'd have known that your nightmares were a normal reaction to the abnormal situation that you faced.”

Howard: Today they would call it PTSD, but at the time they called it something else – shell shock.

Yvonne: Right. Or battle fatigue.

Howard: Battle fatigue, right.

Yvonne: He said, “Well, what do you mean am?” I said, “Well,” I said, “people who witness traumatic events, those memories last a lifetime. And it is very much a real thing that people have nightmares reliving and trying to work out what had happened to them.” I said, “But in psychology we now know that there are things that we could do which would have helped you to deal with them in a vastly different way. And you didn't have that.” And I said, “So what I want you to know is that you're just normal and your nightmares were normal.” And I could tell from the sound of his voice when he came back on that there was such relief. I said, “There wasn't anything wrong with you, you know, at all.” And I said, “You didn't talk about those nightmares because if you did back then you were thought to be crazy or you were chicken.”

Howard: Right. Men were supposed to be stoic and hold it all inside. And I forgot to mention that in my introduction to you, that you are also a psychologist. So I wanted to ask you to psychoanalyze yourself a little bit. How important was it for you to have that kind of closure with your father before he passed away?

Yvonne: It was probably one of the most healing things I've ever done. When I talked to you at the beginning when I said not having the relationship with dad that I wanted, the process of doing the book together, I got the relationship that I wanted. He trusted me with talking about his death and dying. He was very open about that. I would just ask him questions and he would say, “You know, sometimes I really just want to go, this isn't fun anymore.” And my response was, “You know, I understand that. I will miss you dearly, but you and the good Lord, talk to the good Lord, you two decide when it's time. But it certainly okay with me that you're saying those kinds of things to me.” The conversations that we had about his nightmares, I mean here was an opportunity for me to give back to my father in the best way possible. It just really strengthened my relationship with him and as I continue to work on the book, it does it even more. The more I get to know about him or the more I get to feel him and his world, the more I have the father that I wanted.

Howard: Well, would you like to read us an excerpt from the book?

Yvonne: Okay. So this takes place when I was ten and he was not going to take me fishing but my mother said “Please.” And I went. Okay. So my father says to me, “You stay here. I don't want you to come to where we are cause you'll just mess up the fishing.” And with that he walked down stream to the boys. I could no longer see him. I was very much on my own. I had heard the sounds of his footsteps on the hard dirt. So I knew he wasn't far away. I was too content just to be out fishing with the boys to realize what he'd done. I was entertaining myself shaded from the hot sun and my spot at the side of the creek was tempered by a wonderful breeze. I cast out and focused on the bobber in the stream while letting my mind wander and daydream.

Yvonne: I was too pleased with the prospect of catching fish to care that dad had left me alone. My 10 year old mind just didn't go there and then it happened. The bobber began to bounce in the water. I knew something was nibbling and I waited my heart racing. When the bobber went under the second time I gave a little tug on the pole. I felt it catch and I knew I had something. I was careful to reel in the line, give it some slack, reel in some more until I pulled my catch onto the bank. “Dad!” Silence. “Dad!” “What do you want?” The impatience was clear in his voice. “I caught a fish.” “Is it big enough to keep?” Did I hear a little respect in his voice? I heard him start to come my way. His footsteps heavy on the path. “Yup.” I was beaming.

Yvonne: The fish was flopping beside me on the ground. I had done it all by myself. I was on the team. I was. He came back along the trail with a stringer in hand. This was a light metal chain that had lock snaps along its length. The snap would open somewhat like a safety pin and a metal wire was thread up through the Fisher scale and out the mouth. Dad showed me how to use it and he put the stringer with the fish attached to the back into the stream. This allowed us to keep the fish alive. Freshness was important. Dad anchored the stringer into the bank beside me and set back off to his own spot by the creek. I called him back twice more, “Dad, I got another fish.” “You know what to do?” “Yup.” I knew exactly what to do. All the way home I couldn't wait to see mom and tell her what happened.

Yvonne: I bounced into the kitchen and showed her the stringer with three fish, the ones I had caught. “How did the guys do?” Mom asked. It was only then that I realized what I had done. I stood there pulling myself up to be as tall as I could. I was so proud of myself and I wanted it all to show. Mom didn't say a word, but a smile spread across her face. I turned away allowing myself to scrunch up my face with a silent “Yes!” I had bested them and in particular, I had bested my dad. What I wanted to say was “Don't say I can't come along, I'll show you,” but I said nothing.

Howard: Again, the book is called Flying with Dad, a Daughter, a Father, and how his World War II Stories Brought Them Closer by Yvonne Caputo. Thank you very much, Yvonne.

Yvonne: It's been a pleasure. Thank you.