In a two-part series starting today and finishing next Monday, the Alliance of Independent Authors #AskALLi team explores piracy and plagiarism and the impact they're having on indie authors as well as what you can do about them. With deep thanks to all of our members who contributed insightful comments and a special thanks to John Doppler, head of ALLi's Watchdog Desk for his contributions to these posts.

This is a three part series, you can find access to the other articles here: Part 2 and Part 3

The Indie Author's Guide to Managing Piracy: An Introduction

Piracy is the unlawful copying of your work, and it’s the most common form of content theft.

In a digital world, piracy is an ongoing headache for indie authors and all publishers.

Most recently, several large US publishers recently filed a lawsuit against an organization called The Internet Archive for copyright infringement

The Internet Archive is a nonprofit that runs an online Open Library, which lends both public domain and copyright-protected work. Unlike public libraries, this private “library” does not pay authors or publishers for digital lending. Rather, it engages in a practice it calls “lend like print”, in which where a print copy is digitized and lent out to people one copy at a time, through controlled digital lending,” (CDL) just as a print copy would be, but without licensing or payment. The practice is widely considered by publishers to be piracy by another name.

In a recent move that seems to be deliberately pushing legal boundaries, perhaps even inviting a lawsuit, the organization set up the National Emergency Library to make the Open Library catalog of 1.4 million ebooks available to be borrowed simultaneously by anyone worldwide, without any compensation to rights holders. Now Hachette, HarperCollins, Penguin Random House, and Wiley US, supported by the American Association of Publishers and the Authors Guild, have sued for “willful mass copyright infringement.”

Like all such law suits, the case is about more than this individual initiative. The suit says, “CDL is an invented paradigm that is well outside copyright law” and calls the Open Library “one of the largest known book pirate sites in the world.”

And yet, piracy is not as black and white issue. Bestselling science fiction author Cory Doctorow is an activist in favour of liberalising copyright laws and a proponent of the Creative Commons organization. Depending on where you stand on piracy, Doctorow's attitude is problematical or visionary. The title of one of his most popular books says it all: Why Authors Should Give Their Work Away, Stop Sweating Copyright and Focus on Building a Community of Readers).

Proving what he preaches, getting one of his e-books is as simple as going to his website and clicking a download button, yet he also sells millions of books. “Clearly, the availability of free copies is not hurting Doctorow’s sales,” says Joanna Penn of The CreativePenn.com and ALLi's Enterprise Advisor, who argues that the idea that piracy costs authors money is based on a mistaken premise.

The Indie Author's Guide to Managing Piracy: What is Piracy? And What is Plagiarism?

ALLi's Watchdog John Doppler

With thanks to ALLi Watchdog John Doppler for his explanations and contributions.

Piracy vs. Plagiarism

Piracy differs from plagiarism in that the pirate unlawfully distributes copies of an author’s books, while the plagiarist repurposes another’s work as their own. This can be unintentional, as when a nonfiction writer fails to properly credit a quoted passage; it can be coincidental, as when two screenwriters independently develop similar plots; or it can be deliberate theft.

They can also differ in legal standing. Copyright is about protecting the commercial rights of the author. Piracy is, at its core, an infringement on commercial rights. However, plagiarism is an ethical failure that may not fit the legal definition of copyright infringement. As a result, incidents of plagiarism may fail to meet the legal requirements of a copyright infringement suit — and often go unpunished.

The Indie Author's Guide to Managing Piracy: DRM

The publishing industry has attempted to discourage e-book piracy by implementing Digital Rights Management, various digital copy protection technologies known as DRM. These technologies don't go after those who engage in piracy. Instead, they aim to prevent unauthorized copying and sharing of a file.

In practice DRM can be cracked, usually very easily, by anyone who knows how. There are also free tools to remove DRM codes readily available online. And DRM places irritating restrictions on the reader.

The only reason to use DRM is because a potential customers want to do something you don't want them to do. If someone else can offer a way to do what they want, they're likely to take it, in which case your DRM is useless.

For more, this Guardian article gives a comprehensive overview of the limitations of DRM

The Indie Author's Guide to Managing Piracy: Can Piracy Boost Your Author Platform?

Thank you to Joanna Penn for her contributions to this and the next section.

Studies have indicated that piracy actually increases sales, both of ebooks and other media. There is plenty of anecdotal evidence that making content cheap and easy to download increases profits. Take, for example, the case of Monty Python increasing sales by 23,000% by releasing free videos on YouTube, or the case of comedian Louis C.K. releasing a DRM-free recording of his performance for $5.

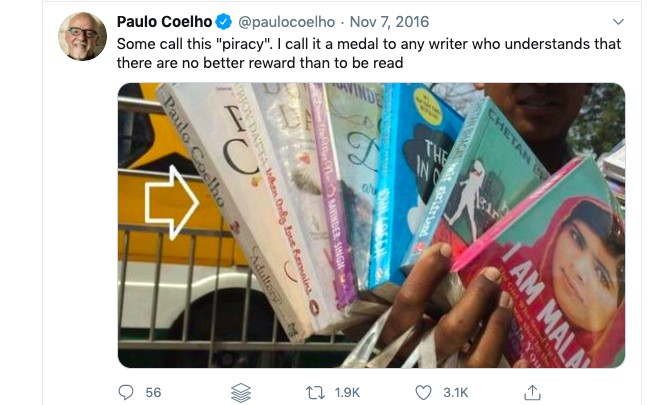

Paolo Coelho is probably the most famous writer to take this approach to piracy, having gone so far as to call on pirates to please pirate his book. Ever since a pirated Russian edition of The Alchemist was posted online in 1999, he has been a supporter of illegal downloads, provocatively calling piracy “a new and interesting system to promote the arts” and entering a partnership with The Pirate Bay–a website that's currently blocked, “pursuant to orders of the High Court”.

.

The Indie Author's Guide to Managing Piracy: Is It Even Piracy?

ALLi's Watchdog John Doppler

Thank you to John Doppler for his contributions to this and the next section.

It happens to every author sooner or later: you’re searching the web for mentions of your book, and on the very first page of search results, some vile excuse for a human being is handing out illegal copies of your work. Shock, rage, and frustration follow.

However, there’s good news: only a tiny fraction of the piracy you find on the web is actually piracy. Most pirate websites don’t actually have stolen content. They use software to gather titles, covers, and descriptions from Amazon or other retailers to use as bait. Then they set up a convincing storefront on the web which claims to offer those books, usually free or for a ludicrously low “all you can eat” subscription.

However, when a greedy fly wanders into this spider’s web, they discover the real price. These operations are fronts for malware distribution, credit card scams, identity theft, affiliate link schemes, or all of the above. There are no free books, and all the victim gets for their trouble is a malfunctioning computer and a decimated credit score.

One popular con is the “recurring billing” scam. The site supposedly offers a free trial, but requires users to enter their credit card information. “You can cancel at any time,” the site promises. The victim cancels but finds that they’re still being billed each month without their consent, and the website operator is unreachable.

ALLi Advice: Do not visit a pirate website to confirm whether your books are there, as this puts your computer at risk.

If most pirate sites don’t have the books they claim to, is it worth trying to stop them?

Chasing down pirates that most likely aren’t infringing on your copyright or cutting into your sales is wasteful. That’s time and effort better spent on writing, editing, refining your marketing, polishing your book descriptions, or a hundred other activities that contribute in a more meaningful way to your prosperity.

On the other hand, many authors feel that having their name associated with a scam could harm their brand, even if their books are not being pirated.

And then there are situations where work has indeed been pirated, and a thief or a con artist has uploaded and is trading in an author's hard work. We have seen this happen to a number of members, who have had their books translated, turned into courses and many other violations of their copyright.

The Indie Authors's Guide to Managing Piracy: Fighting Back

If one of your books has been pirated i.e. somebody is charging money for it, and you are not of the mindset that piracy helps build your author platform, the DMCA takedown notice is your first port of call. DMCA stands for Digital Millenium Copyright Act, a US law that requires internet service providers to remove infringing content.

A DMCA takedown notice can be a cost-effective and quick way to remove material that infringes your copyright, giving you some power to protect your rights if that is what you wish to do. At the same time, the DMCA takedown mechanism has certain safeguards in place to protect the rights of those who have a right to publish material that is not infringing. This is important as copyright law protects the rights of readers, researchers, and information dissemination also.

Technically, DMCA law only has jurisdiction over companies operating in the US, but notices filed from around the world are regularly acted on. The US law covers Google, Microsoft, and Yahoo!, which collectively account for 96.3% of English-language internet searches. And the DMCA-like legislation has spread to other territories, like the EUCD in the European Union and Bill C-11 in Canada. Many governments have now enacted laws making compromising DRM illegal (even if no copyright infringement took place)

A takedown notice should be addressed to the Online Service Provider (OSP) and ask them to remove or block the offending pages. A takedown notice has no set formula but should contain the following:

- Your name.

- Identification of the work that has been infringed (or a representative list of such works) with titles and URLs.

- Identification of the material that is infringing and which you wish to have taken down or blocked, with enough information to allow the OSP to locate the material e.g. link to the offending page.

- A screenshot of the infringement.

- If you have already attempted to contact the owner of the website, provide proof or evidence of this.

- A statement that you have a “a good faith belief that use of the material in the manner complained of is not authorized by the copyright owner, its agent, or the law”.

- Your signature as the copyright holder.

- Ways for the OSP to contact you, such as an address, phone number, email address.

- It's also important you state that you have the right to submit the DCMA because you are the owner of the IP / copyright.

Dave Chesson, in this fabulous article on ebook piracy suggests you should keep your complaints formal and use some legal ease too. For example, key phrases like complaining in “good faith” and “under penalty of perjury, the information contained in the notification is accurate”.

Other Ways to Fight Back

To be clear, if your book is being pirated on a phishing site, then as per John's comments above, do not contact them. However, if your work is being traded and someone is earning from your IP then you should take steps to reach out. Your first port of call is to attempt to contact the owner of the website. You can do this by either using the contact details on their site or using a specific host searching engine like Hosting Checker or Who Is Hosting This? or Who Is? Unless the owner of the website has paid for privacy, then the original email address setting up the website will be noted there. Failing that, the contact details for the host of the website will be available. You can visit the host's website and use their contact form or use the email address provided through the search. Make sure you provide as many details as possible. Again, if this fails, then the last piece of contact information on these searches will be the registrar email and again, you can use this to reach out. Provide all of the information listed in the DCMA above.

The Indie Author's Guide to Managing Piracy: PA's Copyright Infringement Portal

Over the years the Portal has sent out millions of notices to infringing websites and supplements these takedown requests with delisting requests for matching search links appearing on Google & Bing.

- The Portal regularly searches sites that the PA classifies as significantly infringing (i.e. it searches specific sites, not the whole internet) and returns links that match with titles that have been entered into the system.

- Users can review the infringing links, report them, monitor the removal compliance rate (where possible) and have full access to their takedown data.

- The PA uses the data from within the portal to better inform their anti-piracy activities, to provide supporting data to interested parties, including government consultations, and to provide outside organisations, including ALLi, with information on scam sites and fraudsters.

The Indie Author's Guide to Managing Piracy: What ALLi Members Do

Is copyright broken when it comes to piracy? No. No more than homicide law is broken just because murders still happen. For the indie author, it's a matter of deciding where you stand and then implementing the process that makes you feel your work is getting the treatment it deserves, without becoming a time suck.

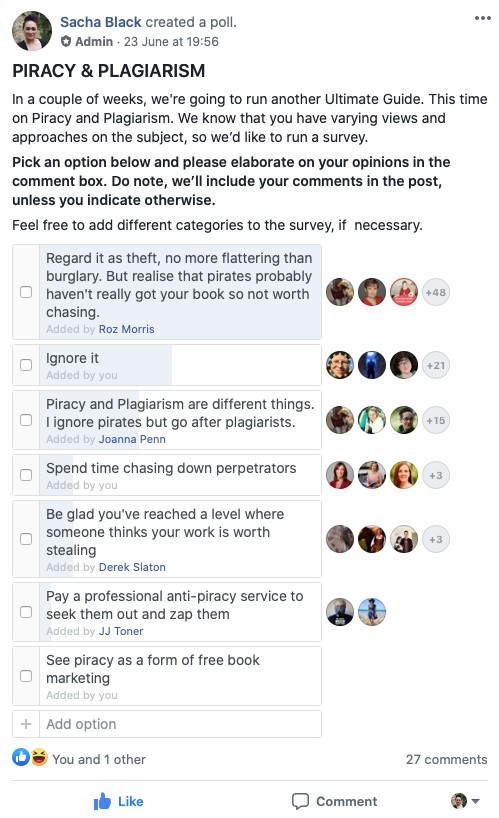

We asked ALLi members how they felt about piracy and plagiarism. Out of 107 responses:

- 48% regard piracy and plagiarism as theft but feel that in most cases “pirates” probably haven't got your book.

- 22% ignore issues of piracy and plagiarims.

- 17% ignore pirates but do pursue plagiarists (more on that next week).

- 5% chase down perpetrators.

- 5% are glad to have reached a level where someone thinks their work is worth stealing.

- 2% pay a professional anti-piracy service.

Our members elaborated on their thoughts about piracy and plagiarism and here is a summary of their responses.

Kevin Partner “I feel that I have bigger fish to fry given limited time.”

***

Elise Noble “A mixture of the above – some websites I’ll send a DMCA for if I think there’s a chance they’ll take the book down. Otherwise I have to ignore it for my sanity. I used to use Blasty before it sadly went the way of the dodo. If there was an alternative out there that was reasonably priced for an author with a large backlist, I’d sign up in a heartbeat. I’m kind of surprised nobody’s jumped into that gap in the market, TBH. There are a lot of alternatives for tracking sales, so there are people with coding ability working in the author services space – I’m hoping somebody might pick it up at some point.”

***

Pippa Lancaster-DaCosta “Some you can't fight, some you can. But don't fall for the “they never would have bought it anyway” BS. Call it out where you see it. Readers need to know it's wrong. Shrugging and moving on doesn't help anyone, and piracy os worse now than ever.”

***

Rohan Quine

Rohan Quine “I'd make a guess that the majority of people have probably become Web-savvy enough, by now, to steer clear of clicking links on pirate sites, simply in view of the well-known danger of catching a dose of malware from them. So I suspect that those pirate links may not be clicked as often as people fear.”

***

Pete D “It's impossible to stop. It's rarely a lost sale, and you might even gain a fan. More exposure is better than less exposure.”

***

Beth Duke “It did not take much time to ask a few websites that actually WERE offering my book for free download to remove it. Will it happen again? Probably. I’m not obsessing over it, but I won’t stand idly by and ignore the theft of intellectual property, either.”

***

Maria Staal “Here in the Netherlands it’s almost a national sport to get as many free ebooks (read: pirated) on your e-reader as possible. I have several friends and colleagues who proudly tell me that they bought an e-reader and got a usb-stick or cd with hundreds of ebooks on it from a neighbour or a cousin. These they use to sideload the ebooks on to their e-readers, then pass it on to other friends and colleagues, as if it’s the most normal thing to do.

Strangely enough these people proudly tell me they have done that, even though they know I’m a writer. It seems as if they don’t connect the ebook they stole with the person behind it, who wrote it.One of my colleagues is the most honest and principled person I know. She once literally said to another colleague, ‘I’ve bought an e-reader and have now hundreds of free ebooks on it that a friend gave me. It’s not entirely legal, but… you know…’

I asked another friend once what sort of ebooks were on the CD she got from a neighbour. Turned out quite recently published books, but also Harry Potter and such. I asked her why she had done it and her answer was ‘JK Rowling has enough money already’.

When I tell people that they’re stealing from the author, they respond that they’d never even thought of that. They feign remorse, but still continue doing it. Very frustrating.”

***

Carole Hocking “My books are mine. I did all the work. Pirates and plagiarists are thieves. If I learn my work has been stolen, I will do something about it. Plain and simple for me.”

For more on copyright issues, download a copy of our Copyright Bill of Rights. Free to members in the member zone. Non-members can purchase a copy here.