Self-publishing, if you're new to it, can be overwhelming. More so if you're neurodivergent. How then, do neurodivergent authors adapt and continue publishing their work? That's the question that the Alliance of Independent Authors AskALLi team is answering today. Here are 7 success factors for neurodivergent and cognitively impaired self-published authors.

Melissa Addey, ALLi Campaigns Manager

Neurodivergent Authors and The Indie Author Survey

The indie author income survey collected and analysed over 2000 responses. And while the results were positive for indie authors, they also pointed up an interesting fact: authors with disabilities earn 27% of the typical earnings of their counterparts. How can we compare this statistic with others? Unfortunately, we can't. While the publishing industry is opening up to include authors with disabilities, most author income surveys don't categorically survey them. Which might mean that the struggles these authors face are not brought to light at all.

In the indie author earnings survey, we included disabilities such as cognitive impairment, mental illness, neurodivergence, sight impairment, physical impairment, unseen disability/impairment and mixed unseen disability/impairment. And while neurodivergent authors earn more than other authors with disabilities, the survey brought to light the reason why authors with disabilities prefer self-publishing over third party publishing.

When ALLi decided to commission our Indie Author Income Survey, we started with just 5 questions but rapidly changed to 20 when we decided to include demographics. This choice was questioned, with some people asking why we needed to include demographics when asking a question about income. The reason was that we wanted to check for things like gender pay gaps, which we could then try to address through ALLi’s campaigns work. Writing the questions was a process which took months and no doubt was still imperfect.

As part of this post’s communications with authors, we did have queries around whether neurodivergence was a disability and it also became obvious that ‘cognitive impairment’ meant many different things to different people. We felt that being neurodivergent and/or having cognitive impairments of various kinds are not necessarily a disability: however, because we live in a society where neurotypicals have created the rather narrow ‘norms' to which people are expected to conform, those differences can often be experienced as a disability because people are not always allowed to shape their working or other environments to do themselves justice.

But however imperfectly worded or categorised, the data which emerged was fascinating and valuable.

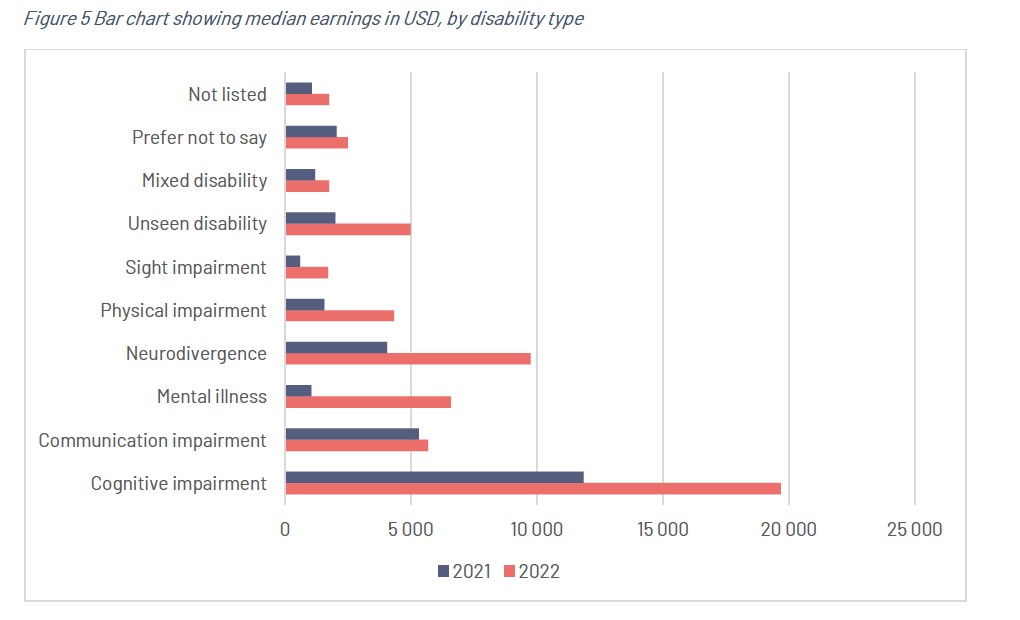

The overall median figure for self-published authors was $12,755 (compared to $6-8,000 amongst traditionally published authors). Within this group, however, authors who classed themselves as having ‘cognitive impairments’ earned more than the typical author ($19,683) and those who chose ‘neurodivergent’, although lower than the overall median, were still above the median figure for authors who classed themselves as having a disability ($4,000) and above traditionally published authors.

Judging by the emails we received, the ability within self-publishing for authors to be truly and authentically themselves, to harness their strengths and make adjustments for their own bespoke needs, is part of what has made this particular group do so well financially and speaks volumes about the society in which we live and its need for change. We hope this post will be of use to authors. Meanwhile, however imperfect the words or categories we used (and we will always strive to do better as we repeat the survey every two years), we have been heartened that self-publishing can suit all authors and are grateful to those authors who have contributed towards sharing their knowledge and skills.

Bar chart showing median earnings in USD by disability type.

What Contributes to Success For These Authors?

“I suppose the shortest way to describe it is ‘time, space, and grace.' This will vary a lot between individuals who have different needs, and I think exploring how well different things work for you and piecing them together to build the best personal system is something that can take a long time and may adapt and evolve over time.” Rory Michaelson

We asked our members to share what worked well for them in the hopes that we could then share that more widely to benefit the wider community of neurodivergent authors and authors with cognitive impairments. More than thirty authors replied and we have chosen to use mainly direct quotes for this post, so that the advice given is coming directly from those with the greatest expertise. Here are the seven main themes that emerged:

1: Control Your Space

Having control over your own workspace was the element of success that came up more than any other:

“I decorate my office so it appeals to my senses, have a desk I can raise so I can stand or sit at my desk, a bottle of water beside me on my desk, take breaks where I get outside and breath fresh air, start the day with a little meditation and yoga/physio exercises.” Tahlia Newland

“I need a quiet and tidy area away from noise and interruption. I also need to be comfortable and take care of my body with where I'm working (many neurodivergent people have HEDS and can end up with terrible pain/injury from working in certain positions of workspace layouts).” Rory Michaelson

“(I need) Inspirational triggers, which occur in: listening to music (the right type for particular characters, places and scenes), videogames, TV/film, nature and so forth.” Melissa A. Joy

“I allow myself to sleep. That’s why I got a sleeping chair in the office. Imagine that, sleeping during the work day!” Holger Nils Pohl

“I’m banging on the door of six figure status and loving writing from home.” Jacki James

2: Find the Tools and Teams That Work for You

“I keep a huge amount of notes and write scenes, chapters, or even whole books on my phone on journeys, and transfer them to my computer to work on later. This allows me to make the most of when my brain and body want to work on ideas and give myself the grace to rest myself more when there are other things demanding my energy.” Rory Michaelson

“I do my writing mainly through dictation. I use the Apple for accessibility software and the Apple dictation as well as the Dragon anywhere app on my iPhone and my iPad. The bottleneck so far has been with the cleanup of the dictation and the editing, so just recently I have also started using AI as well and I am extremely impressed with Magai.” Daniel D. Bate

“I have a publishing assistant who does the project and data management, a book designer who manages the whole process of creating the cover and interior files, and a great editing team. I feel I can trust them all to do their jobs and do them well, and that trust is important to me.” Tahlia Newland

“Spreadsheets to keep track of promotion dates, a calendar to keep track of outside events such as book fairs or times that you plan to write or market. The Pomodoro timer (for sprint writing). Consider getting a digital notebook. I have a Remarkable 2 and it's the best investment I ever made. Digital notebooks like this are especially helpful for two reasons. One, by having one central place to write all my notes in, I don't get distracted trying to keep track of millions of post-its, scraps of paper, or journals. And two, unlike a regular tablet, digital notebooks don't allow you to install apps, so you can't get distracted by social media or games while writing.” Jack A. Ori

“I have found software like Sudowrite and ProWriting Aid really help my writing. Scrivener is my go-to tool on writing, getting the font size big and bold helps so that I do not get lost in words while writing.” Susanna Heiskanen

“I'd take probably a year to write a book of it wasn't for sprints. If I'm by myself I use the Forest app (iphone) you set the timer and you grow a tree as you focus. If you grow enough trees you can put your points towards growing an actual tree in the Amazonian forest. If one of my friends is around we'd call each other and mute our phones then go at it, checking in every 20mins or so.

And the best one – Discord there's a sprinting bot which makes the sprint a bit of a competition with other people. I recently read Take Off Your Pants and this book was a game changer. You think about the character arc rather than outlining chapter by chapter and once you have it you create everything around that. And yes. My stories often go off course, but I don't have those idle moments anymore where I'm trying to figure out where I'm going next. Brain.fm They're not cheap, but my god do I find the neuro effect helpful!

I'd strongly recommend giving the free trial a go and seeing if it helps you! My alpha readers. This is a group of 4-5 people I trust who love my writing and are ultra fans. I write something then put it on google docs for them and they eat it up like chocolate. The love I get from them keeps me going until the book is finished. It's honestly the best dopamine hit ever.” Jo Preston

3: Work in Blocks of Time

“I’ve written over fifty books, first in 12 hours a day (until recent illness made this no longer possible) … I now work in two blocks of 1.5 hrs each, Mon-Thur on writing, Friday for other work and the irony is I am almost as productive now as I was in 12 hours.” Kevin Partner

“I typically do one major outreach a day. Meaning I write a message, Instagram direct message or email to ONE important person for my marketing (maybe ARC reader, podcast interview pitch etc). If I manage to do that, I’m happy and proud for myself.” Holger Nils Pohl

“I try to set aside at least one hour a day to write, or work on book marketing. That way, I’m making some progress as an indie author each day. Do I succeed? No, but when I don’t get time to work on my author projects, I know that I can try again tomorrow. I am human.” William Brinkman

“Whenever I went to writing conferences I had to pace myself. I sought out quiet spots, even if I had to return to my hotel room, to take a break between sessions. I ate alone if I could. My brain needed rest to function, and that meant avoiding conversations and loud noise whenever possible. Sometimes I skipped sessions, especially if I knew a friend was going and could give me a report later. Virtual meetings that are recorded have been a godsend to me.” Victoria Noe

4: Don’t Feel Obliged to Follow All the Advice!

“The idea of going to a conference horrifies and mystifies me.” Kevin Partner

“Writing in a café is great for a lot of authors, but I find it distracting.” Robin Philips

“When you're neurospicy, certain pieces of writing advice are counterproductive. This approach of ‘edit, edit, then edit some more, and when you think you've edited enough, you fool, you're only 10% of the way through your editing!' is potentially catastrophic. For me, demanding that I work on the same manuscript ad infinitum is like asking me to rub sandpaper on my brain. My love for the book I'm self-publishing in November was killed by trying to follow this advice. I'm still self-publishing the book, but I hate it as a piece of fiction. This experience made me swear to edit my next book less. I want to self-publish the next one whilst I still love the book. Don't let neurotypicals shame you for writing the way you want to. Editing definitely makes your work better, but endlessly editing doesn't.” Michael Coolwood

After decades of learning the skills I need to write well and consistently, I finally started rejecting and unlearning the sometimes aggressively unhelpful advice handed out as gospel by neurotypical writers and coaches, who tend to assume we all think and learn the same way. Rather than “eating the frog” (doing the hardest task first), I make myself a dopamine sandwich. I do something that makes me happy first, then surf that dopamine wave through the frog—then reward myself with another dopamine hit as a prize. Vicky Quinn Fraser

5: Sensitivity to Rejection Is Something to Manage with Care

“A lot of the stressors around traditional publishing push me out of my comfort zone. Mostly rejection is a tough pill to swallow and many people are now known to be rejection-sensitive or worse have RSD. “Rejection sensitive dysphoria (RSD) is when you experience severe emotional pain because of a failure or feeling rejected. This condition is linked to ADHD and experts suspect it happens due to differences in brain structure.” If you want you can read more about that here. Amy Ayres

“Pushing a social media presence when you have rejection sensitive dysphoria is honestly just wild.” Rory Michaelson

“Put a 24-hour moratorium on responding or making any decisions after getting feedback. Whenever I get critical feedback from a beta reader or editor, my initial reaction is always to assume that the reader is wrong and didn't “get” that I did this for a reason. It's important for anyone to sit with feedback, but I suspect my neurodiversity makes this especially vital. It takes about 24 hours for me to calm down and be able to consider the feedback more objectively.” Jack A. Ori

6: Rest Before You Stop Altogether

“Sometimes I hit optimal conditions and my hyperfocus will kick in and I can write first draft of a novel in a week. Other times, I'm overstimulated or on the edge of burnout and writing is incredibly difficult for months. Rather than force myself to ‘write every day' I write when I have the capacity to do so. This keeps me from burning out and allows it to me an enjoyable and positive experience, rather than something I try and force myself to do a bad job and maybe even end up shutting down or burning out, which would impact my health and productivity much more.” Rory Michaelson

“I'm not on anyone else's timetable. When I feel like I'm not inspired or getting burnt out, I take a step back and try to reorganize my schedule, take things off my plate.” Ashley Kusi

“I can set and move my own deadlines. If I need rest, I do. I work when I feel like it and don't get upset too much when I don't write. I don't feel pressured to write either, if I am unable to.” Julie Day

“I pace my workload to manage overwhelm. Set super realistic targets. Task bundle to make best use of my hyper focus. Don't hide when I am struggling to process with my designer/narrator etc. and need more clarification. Remind myself its supposed to be fun!” Eden Gruger

“What has helped the most is a trick from my neurologist: go to it, not through it. When I have focus issues, I stop working. I do something else, maybe related, maybe not. Or I do nothing (there's a difference between resting your brain and resting your body). It gives my brain a chance to rest and restore. No more pushing until I'm exhausted.” Victoria Noe

7: Know Yourself: Leverage Your Strengths and Work with Your Weaknesses

“I get resistance to change because of my autism. If you're the same, try to push through that to give things a genuine chance. Sometimes the gut feeling is railing against the change process, rather than what you're changing.” Robin Philips

“I love editing, and it's my perfect job because it uses my special skills – my brain is wired for deep understanding of the written word. It took me a while to work out how I could capitalise on my strengths and not allow my difficulties to stop me from being an editor. The penny dropped when I realised that I could specialise in my area of expertise – line and developmental editing – and leave the area where I'm not so good – proofreading – to a colleague.” Tahlia Newland

“They say, ‘write about what you know'. I live Tourettes, so I have written about it authentically and with empathy, without preaching.” Jill Metcalfe

“It's the squeeze on my brain as a deadline approaches that provides the magic juice to provide that ‘ending I didn't see coming' which is a refrain in so many of my reader's reviews. My habit of leaving the conclusion to the last minute might be infuriating to colleagues in a traditional work setting, but working as an independent author (means) I can harness the ‘talent' once derided as a failing.” Beverley Oakley

“Do the work that excites you most first — but set a timer. Often, once I get into a new project, it consumes me and I find it hard to focus on doing anything else. Obviously, if I allow myself to hyperfocus, I won't accomplish the less exciting tasks I need to complete to be successful, whether that's promoting current work or doing my accounting for the month!” Jack A. Ori

“I remember calling Ingram Spark in tears because I couldn't do a form they wanted me to because I was taking some of the language too literally and they helped me out!” Rory Michaelson

“My autistic son used (writing picture books) as a way to help his language, he wrote and published two books in ninth grade and almost 4 years later, has started emulating Dr. Seuss with his new work and draws and writes all his own material.” Brendan P. Kelso, father to Keagan ‘Doc’ Kelso

“I don’t like socialising. You know what? That gives me more time to create! I hate making mistakes! You know what? My products are highest quality! I need more time! You know what? That leaves room for learning from mistakes of others in the industry!” Holger Nils Pohl

“The biggest help for me has been getting to know my target audience: they enjoy finding me at historical sites and purchasing signed physical copies of my books there. It's a bonus for them and often a draw if I do a presentation and book signing at a historical site. So there's an experience that they're looking for, and my physical books and I deliver a big part of that experience. Getting to know my readers has been a tremendous de-stressor for me.” Suzanne Adair

“My first book was traditionally published and secured a large advance with contractual obligations such as a book tour of public speaking. This stressed me so much that I ended up in hospital with heart investigations. This time I am self-publishing so that I can control my exposure to ‘the public.' I turned down an offer from a publisher because their idea of ‘success' terrifies me.” Cindy Engel

“I have the ability to process large amounts of information and predict what will happen next in a complex system. There's a saying in high-tech data management (where I used to work): garbage in, garbage out. My predictions were only as good as what I put into my head. In other words, I've found it's important to read and learn about new things. For instance, I'm going back to get my Master's in History from Harvard and just finished a class on Benjamin Franklin. After I launching a recent book, I noticed how home of Franklin's ideas about lightning helped me develop new lightning-based magic.” Christina Bauer

Does This Advice Apply to You?

The experiences here all come from people who classed themselves as being neurodivergent or having cognitive impairments. But in sifting through the answers to find common themes, two things quickly became apparent. One was that a lot of this advice could be applied more widely. Taking the time to understand what truly works for you as an individual, giving yourself ‘time, space and grace’, is something we all could learn from. The second was that many authors referred to late diagnoses especially in relation to neurodivergences such as autism and ADHD. This reflects what is going on in society at the moment, where many people are realising that they might well be neurodivergent but were never diagnosed. So we urge all our author members to reflect on what they can learn from this group’s success and consider how it may apply to their own situation.

“I am without doubt that there is a hidden population of undiagnosed Autism in the writing and author community. Why? Because Autism is a communication difference/disorder, and we gravitate to our most comfortable mode of communication, which for many Autistics will be writing over speaking. We are often voracious readers and subliminally learn to write from this. Some will be self-taught readers at a very young age. My own preference is writing over speaking. I write better than I speak, and my emails are often longer than I intended (point in process as I write). Hidden Autistics will be writers, musicians, computer coders (this is a form of communication) and use a variety of other preferred ways of communicating (not all viewed as socially acceptable).” Jane McNeice

ALLi could not have written this post without you

“I hope (this advice) helps. You would do me a great favour if you answer me, if this was helpful or if you expected something else. It cost me more energy than I had left for this day, to write to you.” Holger Nils Pohl

I’ll confess that this line, from Holger Nils Pohl's email to ALLi, made me well up. Over the past few years I have found out that not only do I have two autistic children but, in exploring more about autism, have realised that it is very likely that I too am autistic (albeit evidently an expert at masking!). So I would like to finish this piece with a heartfelt thank-you to all the authors who took the time to respond, often in great detail, to our request for information. The self-publishing sector is known for the willingness of its authors to reach out and help fellow authors by sharing tips and ideas for greater success (for any given measure of success). For those authors who have limited time, ability and energy because of their own cognitive impairments or neurodivergence, the effort this reaching out requires is substantial and I have been touched by your generosity in using up some of your spoons* to help ALLi write this post.

* The spoon theory is a concept developed by Christine Miserandino, which refers to having only so many ‘spoons’ (units of energy) available to you a day and that when those units are gone even simple tasks may be beyond your capability. It is commonly used in the neurodivergent community and by people with chronic illnesses.

Dan Holloway, ALLi Self-Publishing News Editor

Writing as a Neurodivergent Author: Dan Holloway

Like many neurodivergent people, I am multiply neurodivergent (ADHD, dyspraxic, autistic) as well as being bipolar, also a common co-occurrence.

This affects my writing, it affects the way I have to manage the business around my writing, and it affects the way I live the whole of my life and all the everyday activities so many people take for granted.

I want to talk a little bit about each of the first two of those, and how accepting that impact, and working with it rather than fighting against it, has been a difficult place to arrive at, because of the pressure in the writing world to follow tried and tested advice, but ultimately a rewarding one.

But first a little about how it impacts my life, and the unexpected paths I have been drawn down as a result, because it’s impossible to understand my writing without that introduction.

Like many whose diagnosis has come decades into life, childhood was really hard. I was always different, but didn’t know why. So I was labelled as lazy by teachers and bullied by my peers relentlessly. University meant I finally met more people like me, though I still had no idea why we clicked. And I still struggled with the way work was done – but never the content of the work.

The constant emphasis on process (processes I couldn’t follow) not output made me increasingly frustrated, and eventually completely burned out, something I’ve never recovered from either in terms of my health, my career, or the debt and trauma a burnout when you have parents who won’t support you leaves you with.

But then when I learned to build ways of living around those differences, in my 30s for bipolar and my 40s for neurodivergences (like many because I noticed people around me being diagnosed with things that explained what I had always thought were just my character flaws) I went down rabbit holes that have been incredibly rewarding, ending up as (like many) a campaigner, speaker, and consultant on these issues, and leaving me with a creative thinking start-up.

These directions have been fascinating and rewarding. But like many people who fall into a group of interest to EDI (Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion) it is sometimes hard to avoid being pigeonholed and asked only to talk or write about that part of my life. Many of us go through a phase where it becomes a real focus (or “special interest” to use the neurodivergent lingo) in our lives. But eventually we want to get on with other things. For me, those are teaching people of all ages how to be creative and writing fiction.

In terms of my writing, I find a lot of traditional advice simply doesn’t work for me, such as “write every day”. For years, I tried to fit myself into moulds designed to work “for everyone.” Only to find that they didn’t work for me. And as a result, I would feel that I was being lazy, not trying hard enough, not trying smart enough. Rather than realising that, my brain simply doesn’t have the preconditions for writing in place on some days.

It was only when I stopped trying to lean in to the “accepted” way of doing things and ask, “what works for me?” that I started not only to regain the pleasure I’d first got from writing before I started thinking about publishing, but to make real progress. That means writing when I first wake up most days. But it also means not worrying about doing that every day if my brain says no.

Another trick many of our neurodivergent brains will play is something called “object impermanence.” And like many things, most people can relate a little. It is essentially the principle, “out of sight, out of mind.” But ramped up to 11. And always on. It’s why we need to make sure we always put things in the same place. Because once we’ve put them down, we have no idea where they’ve gone. And it’s what many forms of note taking don’t work. Because if you have to follow links or go to separate sections of your journal, they might as well not be there. Everything you need has to be visible. In one place. At the same time.

I’ve had to develop a whole new way of journaling to avoid tasks simply being ignored. And characters/plot notes getting overlooked entirely. But that was possible once I acknowledged it was needed.

There is a whole self-help industry it seems around building habits to overcome brain resistance. But when you're neurodivergent, that can be really damaging. Because the way your brain is behaving isn’t driven by conditioning but by wiring.

And the answer is to work with that wiring. Writing to deadlines is a great way for me to do that with ADHD. But they have to be genuine deadlines. Only then will my brain kick into a new gear from “mulling” to “downloading to the page” as if by magic. It’s one reason why writing the ALLi news column works well. Likewise, writing for presentations and conference talks, and then working those long form essays into a book structure.

What happened with my writing happened even more with the administration around that writing. The internet, advice forums, dare I say it, advice books, are full of things aimed at “everyone”, which can leave you feeling, again, a failure if it doesn’t work for you. One of the features of my ADHD, for example, is executive dysfunction. This means I struggle with various forms of administrative task. Anything involving multiple stages can be almost impossible. Our brains disambiguate every single stage of a process so that each separate part needs conscious attention for successful completion. Nothing can be “taken for granted” or “automatic as it is for most people. Which makes instructions unnavigable in many cases.

I also find it almost impossible to use the telephone because of the way my brain processes information, and add anxiety to that and I cannot take incoming phone calls at all. All of that means many of the traditional ways business is done are simply not available to me. Finally, my health can be very episodic. I get windows of clarity that can last weeks. But then my brain can shut down almost entirely and make day-to-day tasks almost impossible. In those periods, I can do very little in the way of admin tasks or planning.

All of the above is one of the reasons I am an indie: for self-preservation because I can’t do things the way publishers require me to. It’s liberating, but it’s also really hard. Because the business world still needs me to do many things I struggle with, even if as an indie I can do them in my own time. And there is no understanding or advice outside of the neurodivergent world, because most people don’t understand that we can’t do things where most people won’t do things.

But I have been able over recent years to make the different way I do things a feature of my brand rather than a bug. My business card doesn’t have a phone number on it. And if you ask me for one, you’ll soon remember me as “the writer who doesn’t use a phone.” You’ll also notice we do a lot of our “business” in coffee shops. Which I guess is not so different from the rest of the industry and probably one reason I’ve been able to survive. Most people just might not realise the reason why,

One of the projects I’m working on right now is an attempt to make the publishing industry more accessible for us as writers, the way it’s doing for readers. It’s built around an open source list of support needs called WhatWeNeed.Support and I hope this bit gets left in so you can go and take a look and get involved.