It's always good to start the writing week with a lively discussion, and the topic of literary fiction, its definition and purpose, is guaranteed to engage the minds of indie authors everywhere. Ann Richardson, whose non-fiction books marshall opinions and research on various topics, kindly volunteered to summarise a vigorous debate between ALLi authors on our closed Facebook forum (an exclusive benefit for ALLi members). If you'd like to continue the conversation via the comments afterwards, we'd love to hear from you – this topic never gets old!

No attribution is given to individual thoughts or even direct quotations, primarily for brevity but also to preserve anonymity. Necessary apologies to anyone who feels their contribution was ignored or misrepresented.

Who Writes Literary Fiction?

The discussion began with the seemingly innocent question from one member asking which others identified themselves as writers of literary fiction. Surprisingly few put themselves wholeheartedly in this camp.

Many members suggested that their books were difficult to classify (“I know what they’re not, but struggle to give them a label”). A considerable number claimed that their writing displayed key elements of literary fiction (“I’m a lit-ficish writer”), particularly good writing (“I like to think of my work as “literary” in the best sense”).

Some felt their writing, although potentially literary fiction, was more usefully described as historical or contemporary fiction. Others created their own dual categories: literary horror, literary fantasy. literary suspense and even “litfic with a touch of magical realism and a dusting of horror”. One offered literary fiction with a plot.

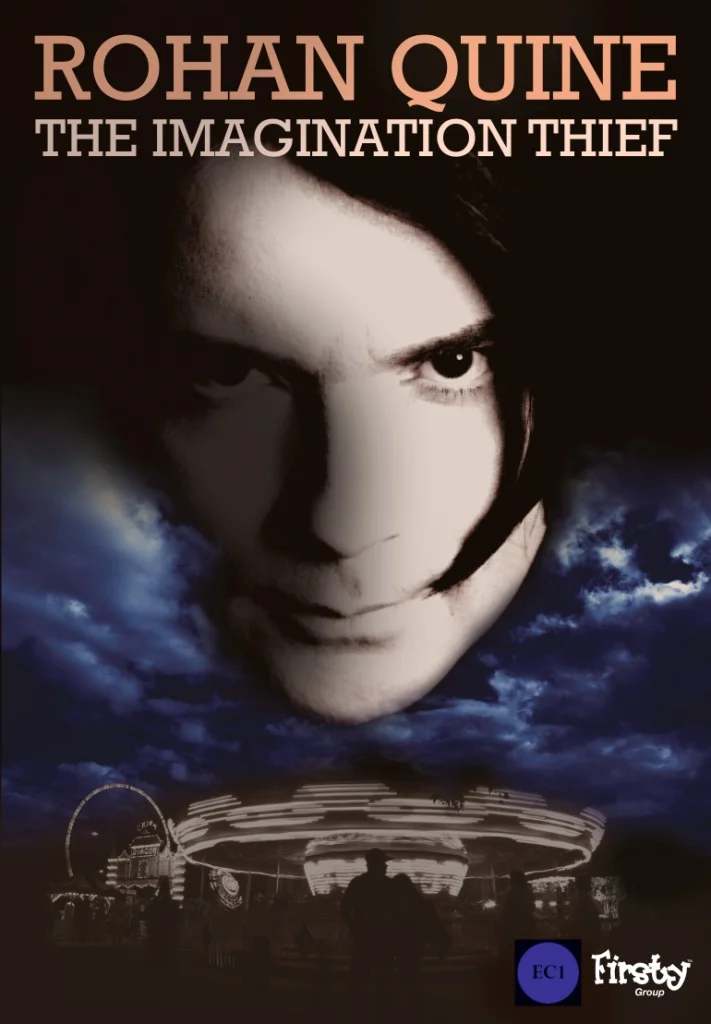

Nonetheless, a few ALLi members were mentioned by others as belonging firmly in the realm of writers of literary fiction: Jane Davis, Dan Holloway, Roz Morris, Rohan Quine, Philippa Rees and Orna Ross (alphabetising intentional).

What is Literary Fiction?

This led to the much more troubling question of what literary fiction is. There was some interest in finding an intrinsic definition, but also a focus on comparing it to more traditional genre fiction.

Some saw literary fiction as writing with great attention to language and style. Sentences would be expected to be carefully crafted, metaphors fresh and clichés avoided, striving for precision. It might also involve experimentation.

Others stressed that literary fiction is more character-driven, with an interest in character development, motivation and complex relationships: “I’m enthralled by the inner worlds and hinterlands of my character’s personalities”. Additionally, one might expect less focus on plot, and certainly less reliance on formulaic plotting.

Yet others focused on the impact of literary fiction on the reader. Its pages may not turn quickly, but the writing makes readers look inward and recognise something in themselves:

“reflect depths beyond itself to reach echoes in the mind, reflections in the heart”.

Or it might challenge the reader in some fundamental way: “books that give me something I have never seen before…it turns the world on its head”.

A number of contributors aimed to define literary fiction in relation to well-known writers, naming too many to be repeated here, from classics to many modern writers.

In the final analysis, many argued that a clear definition was both impossible and inappropriate:

‘the taxonomy of ‘literary’ and ‘genre’ fiction is misleading”

Any definition was likely to ignore or diminish the many accomplishments of the best genre writers,. for instance, a note of the “wonderful prose, dynamic plots and superb characterisation” of some crime novels. If the aim was to tell a good story, many books were both literary and genre, and some of the latter might one day prove to be classics.

Indeed, the label was unhelpful, set up for marketing purposes, and most readers were unlikely to care.

Very little attention was given to the concept of literary non-fiction, aside from noting that some narrative non-fiction books might be included here.

Some Reflections

Overall, there was a considerable dislike for the term literary fiction. It was seen to have pejorative overtones, too often implying a boring and/or pretentious work (“doorstep-long triumphs of the beautiful sentence and painstaking research over ideas and innovation”), with a poor or non-existent plot and little good reason to read it (“low or negative payoff”). Indeed, a few saw the broad label as a warning: “if a book is described as literary, I’m inclined to look elsewhere”. Moreover, some noted, it could prove difficult to sell.

Much of the heat in the discussion arose from the feeling that literary fiction was sometimes deemed to be more worthy than other genres: better written, more thought-provoking, altogether a higher art. It was important to recognise the many exceptions, although it was also inappropriate to compare the best of one genre with the worst of another.

With respect to their own writing, many members agreed that their main aim was to write what they chose and “not feel trammelled by genre”. This led to another discussion about the potential conflict between following one’s own muse and selling well. Any summary of this issue must await another day.

There could never be a simple conclusion to such a discussion, but in short, literary fiction means different things to different people. What does it mean to you?

Postscript

On the day I began this post, my husband and I discussed it briefly. That evening, he read me a passage from the book he happened to be reading. It was a talk by William Waldegrave at a dinner to honour the novelist Patrick O’Brian. We are here, he began:

to celebrate and to honour one of the greatest storytellers in the English language. I start with that word – storyteller – designedly. There are, or used to be, some in the world of English literary studies who regard the capacity to tell a story as being a most deadly disqualification from serious consideration. Only if a book proceeded in a properly inconsequential manner, only if the naïve could be trapped into the ultimate solecism of enquiring what it might be about, only if the pages might be bound up in all manner of different orders without difference to the sense – only then could the thing be taken as high art.

Full speech published in Patrick O’Brian, The Yellow Admiral, HarperCollins, 1997

Starting the #writing week with an ever-topical debate: what is #literaryfiction? - #litfic Share on XFURTHER READING – or rather, watching… a memorable video on the topic from two passionate proponents of literary fiction

[…] nature of the genre is difficult to define, a topic Ann Richards explored on this blog last year. Another challenge is that the literary community leans toward traditionally published works. In […]

[…] (In the meantime, in case you missed it, two pieces about literary fiction have recently appeared in ALLi’s Self-Publishing Advice Center worth checking out: Dan Holloway’s “Where is the Great Indie Literary Fiction?” and Ann Richardson’s “What is Literary Fiction Anyway“.) […]

[…] This was originally published by the Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi) on 17 October 2016. (https://selfpublishingadvice.org/opinion-what-is-literary-fiction-anyway/#comment-633037) […]

I thought this was a very interesting discussion and it prompted me to write my own blog article on the subject. For me the difference between genre and literary fiction lies in the “page-turning” nature of genre fiction as opposed to the “being in the moment” nature of literary fiction. You can read my post here: http://www.thegoodwriter.com/the-difference-between-genre-fiction-and-literary-fiction/

[…] out this discussion about the definition of literary fiction and add your opinion. While you’re at it, here’s literary agent Donald Maass’s […]

Here’s literary agent Donald Maass on the perennial question: https://justcanthelpwriting.wordpress.com/2016/06/01/what-is-literary-fiction-donald-maass-has-a-definition/

I found this discussion summed up a lot of my own sense of whether I’m in “literary” territory or not as a reader. I always fall just a hair short of this definition as a writer, yet hover always just outside of “genre,” whatever that is.

And I have to give a shout out to the mention of Patrick O’Brian in the article above. I don’t give two hoots whether POB is literary or not. If you want hours upon hours of some of the most engrossing reading you’ll ever do, get started. Read the books in order. Storytelling at its best.

For me, the word “literary” is rightly applied to a work of fiction when the reader finds himself/herself thinking about what’s being said and done by the characters, both when reading and after. Non-literary work invites the reader–for want of a better term–to ingest it. Stories meant to be ingested are analogous to jelly beans. You enjoy them as you quickly eat them, and go on with your day without giving them much thought. I find myself thinking about events and characters in Ruth Rendell’s novels, and in those of Elmore Leonard, and those of Kate Atkinson. But most of their competitors aren’t writing literary crime novels, nor are they trying to. These other novelists are writing for an avid, consumption-oriented readership. That said, it should also be added that you know when you’ve eaten a good jelly bean, and when you’ve gotten a dud.

An excellent article, thank you Ann Richardson. It’s a topic close to my heart and in fact I wrote a blog on a similar theme just a week ago. See https://wordpress.com/post/barbaralamplugh.com/671

I have never understood why genre work can’t strive for the highest qualities of language usually designated the province of litfic and equally why so-called litific can’t partly devote itself to telling a story with an engaging plot. To me there is really only fiction and non-fiction, it’s the pesky sales and marketing teams and internet algorithms that demand to catergorise and atomise literature to make it searchable.

I can’t define my own work in terms of labels. It isn’t about story (though it’s likely to be about the storyteller/narrator). It’s not really that taken with character, but does pursue voice which subsumes character because you can tell a lot from how a character speaks and frames their thoughts and don’t have to resort to artifice such as backstory or conflict for the sake of conflict. Language is a high, if not the highest value for me in my writing, but largely as a tool for breaking through the membrane of occlusion it helps establish in our lives – to communicate we have to share understanding but that can be necessarily reductive, like how our visual cortex reduces perception to not what is ‘seen’ but what the eye expects to see.

What people dub litifc can and in my case always is, be concerned with the nature of fiction compared to the real. The book interrogates the liminal status a reader finds themself in when reading the words of an absent author and a world that may or may not approximate his/her own. There lies a tension, not in any ‘suspension of belief’ way, but an ongoing dialogue throughout the course of the book, endlessly reflecting and refracting back on the relationship of fiction to reality.

Yup – especially that last paragraph!

Super job, Ann, with a difficult subject!

Despite being quoted in the pejorative section, I adore literary fiction and will head for the literary fiction section of any bookshop I’m in. Maybe I’m spoiled because in Oxford we have Blackwell’s whose literary fiction section is curated by Ray Mattinson who is famous nationally as one of the UK’s best booksellers and has been the driving force behind Blackwell’s championing of small presses (they devoted a whole table to Galley Beggar before anyone knew who they were, and more recently Fitzcarraldo) and organising of mouthwatering events, especially with leading South American writers (tonight, for example, Alejandro Zambra is coming to talk about Multiple Choice), and Ray’s taste is instinctively the same as mine – for the kind of book that changes the way you look at the world.

Literary fiction can be, should be, a mine of dazzling, innovative, extraordinariness that comes in all shapes and sizes from the slenderest volume such as Zambra’s Bonsai to sprawling visions like Danielewski’s House of Leaves. But for me a literary book is one that is aware of its place in an ongoing conversation and seeks to add something to that conversation.

The term has been somewhat usurped in many circles for the “doorstep-long triumphs of the beautiful sentence and painstaking research over ideas and innovation” that my comment referred to, books that seek to succeed in and of themselves, or to demonstrate the author’s brilliance, or to impress – books whose frame of reference is contained inside their covers, as opposed to books whose frame of reference only begins where their covers end.

And we indies are really really bad at helping the cause, in part because so few write the kind of literary fiction I am talking about (most new writers of that kind of book head for one of the many small presses championing such work, a situation that has improved manifoldly in the past 10 years), and in part because in our bid to be supportive we end up pointing the world to what we say is great literary fiction that really *really* isn’t – most discovery sites have a literary fiction category, and to be honest (and I include Amazon’s Powered by Indie”) almost all of them make me want alternately to cry, throw something, or just throw up.