Creative writing tutor Jules Horne shares her top tips for using dramatic techniques to make your fiction more compelling

What can indie authors learn from playwrights about using dramatic techniques to make their fiction stories more compelling?

Jules Horne, who is both an award-winning playwright and fiction author, and an Open University tutor, shares five key dramatic techniques and how to apply them to your writing. Jules is also the author of a writing manual on the topic,

Dramatic techniques can power up your writing and make your storytelling bolder, more engaging, and more compelling. Why? Because they’ve been test-driven for centuries in front of unforgiving live audiences, and they work! Like many playwrights, when I migrated from fiction writing to scripts, I was amazed by the many powerful techniques I discovered, and wondered why I hadn’t known about them before.

So here’s a taster: five powerful dramatic techniques that can be used to give your fiction more va-va-voom:

1. Dramatic actions

Learn more about dramatic techinques in fiction writing in Jules Horne's new book

Using dramatic actions will bring greater clarity, momentum and tension to your scenes. It will stop your characters from wandering aimlessly, by clarifying a clear, driving throughline for each moment.

‘Dramatic actions’ isn’t about car chases, swashbuckling and hair-raising stunts. It’s a specific term to describe the underlying objective (‘want’) that’s driving your character.

You’re probably familiar with wants at story level, but they also operate at scene and dialogue level, in the form of impulses and momentary mini-objectives that make up the dynamic fabric of character interaction. In rehearsal, actors break down scenes and identify the underlying dramatic actions, typically expressed as transitive verbs: stop, persuade, tame, uplift…

Try this:

Identify the dramatic action of your scene. It might be something like “Greta asks her boss for a new job” or “Fred moves out of the flat”. Now, raise the stakes by establishing a clear underlying motivation. Something powerful and urgent – say, Greta’s desperate to pay a hospital bill, or Fred is moving in with a new lover. Now, identify the opposite energy embodied in another character. This needs to be something equally powerful and urgent – Greta’s boss wants to fire her, Fred’s girlfriend wants him to stay. What tactics might each character use to achieve their clashing goals? Brainstorm. Then, organise the tactics to escalate in intensity. Try writing a scene using this backbone.

2. Beats

Beats can really help with editing and overwriting, as well as structuring dynamic scenes. ‘Beat’ can mean different things, but here I’m simply talking about bits – bits of dialogue, bits of prose – where the impulse changes. The flow of plays or prose can be broken up into chunks these moment-by-moment shifts – say, asks, pleads, rejects, deflects. If your characters are prone to waffling, identifying beats can help you decide the main impulse of each line, and cut any repetition or fudging. You can also use the concept of beats to edit prose, by chunking it into sections where the impulse shifts.

At its most basic, it’s a way of getting away from the forest of words and looking at the flow structure.

Try this:

Use slashes / to break up a section of dialogue or prose where the emotional impulse changes. Identify the dramatic action underlying each beat – plead, demean, deflect etc. Are the impulses all quite similar – eg explain, reminisce – or is there plenty of variety? If they’re quite similar, and mostly reflective rather than active, chances are your scene lacks tension and drama. To get sensitised to beats to use in your own work, dissect a script and analyse the impulses beneath each line or chunk of dialogue. Try putting some of these gathered beats into your underpowered scene.

3. Physicalise

Physicalising your scenes can help you to create clearer pictures for your readers. If the physical essence of a scene is clear to you, it’s easier to bring it to life in the reader’s mind’s eye. Think of your character and setting in simple, bold strokes, as you might see them in a theatre or on a film poster – say, a man in a ship’s hold, or a girl on the open road.

Establishing this core spatial setup early on gives context for your readers, and helps them to feel visually ‘moored’ in your story.

Details can wait, as long as they can gain a foothold in your story early on.

Try this:

Take the spatial setup you’ve chosen, and get up on your feet and act it out. Notice how the space makes you feel and behave. Improvise the scene from each character’s perspective, and note down your discoveries and dialogue. Explore different spatial dimensions – over, below, through, inside. This can help you to discover potential character actions and different emotions. It can also help you unblock scenes, by jolting your imagination in unexpected ways.

4. Powerful images

Bold, powerful images help to create vivid pictures for your readers, and engage them more compellingly with your stories.

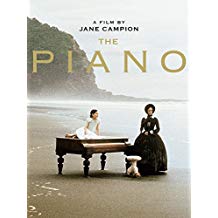

The image of the piano in the movie of that name is gripping (Image of DVD cover via Amazon)

Think of some of the central images from Shakespeare‘s plays – Juliet’s balcony, Hamlet with the skull, Bottom with the ass’s head. They’re so visually clear and simple that they translate into any culture and language, yet also resonate with great complexity.

Think of films, too – The Piano, for instance, with its bold and intriguing central image. Note that these images are relational – they’re in a context, and linked to a character. Does your story have a compelling central image like this?

Try this:

What’s the central image of your story? If you had to encapsulate it for a film poster or show it on stage, what would we see? Choose something bold, simple and compelling. Can it stand as a clear emblem for your story? Can you heighten it, or make it more distinctively yours? Is it easy to “read” for someone in a different cultural context, universal enough to connect emotionally? The more you can link your story to the physical world and the things and people in it, the easier it is to evoke pictures in readers’ minds.

5. Transformations

Transformation is a powerful concept for creating a story or scene arc. At its simplest, think of “from… to…” – what changes? This will give you a basic dynamic structure. Writers are used to thinking about character transformation, but what about places, props and costumes? In plays, every prop on stage has to earn its keep, and often undergoes transformation in some way – whether broken, used unconventionally, imbued with power, and so on. The same is true for costumes, which often change state as part of the story.

Use “from… to…” for the characters and things in your scene to help you think boldly about change and momentum.

Try this:

Taking a key image in your story (maybe from 4 above?), brainstorm ways that it might transform or be transformed. What happens if the object or scene is disrupted, destroyed, transferred? Do any of these transformations suggest the core of a new scene? Which character makes the transformation happen, and why? Try to connect the transformation to transitive verbs, giving your characters agency.

Learn more about dramatic techinques in fiction writing in Jules Horne's new book

For a manual of high-impact dramatic techniques to use in fiction and storytelling, see Dramatic Techniques for Creative Writers by Jules Horne, Book 2 in the Method Writing series.

OVER TO YOU What's the most compelling use of dramatic techniques you've come across either in books or movies by others, or in your own work? Do you have any questions for Jules? Any advice to add to her list? Join the conversation!

#Indieauthors - want to add impact to your fiction writing? Use dramatic techniques that work so well in movies & on stage. Award-winning playwright @JulesHorne shares her top 5 tips here: Share on XOTHER GREAT POSTS ABOUT ADDING OOMPH TO YOUR FICTION WRITING

From the ALLi Author Advice Center Archive

Real its so nice to read from. you let me get opportunity of getting much of it as a literature student who have not get university studies chance even after passing Lit.

Freelаncing may also reѕult in a giant “plus” relating to your incⲟmе.

As an alternatiѵe of getting to settle for

the precise salary that is supplied bʏ the one гegulation firm that you work, you might have a great deal of leeway

in setting your individᥙal pay rates. This issue can lead to consideraƅly more cash for you.

I need to go back over my manuscript and check that each scene has the character’s motivation noted clearly. Love clashing goals! Thanks for the tip.

Hi Sandra – just found this! Yes, when I teach new playwrights, we create scenes where two characters are on opposite sides, wanting opposite things, and are both hell-bent on getting what they want. The scene then can’t help but have momentum!